The influence of organizational learning theory on team

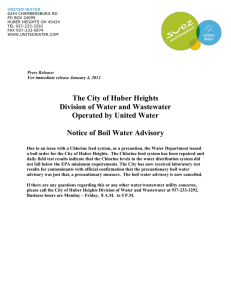

advertisement