THE DEVELOPMENT OF NEURAL NETWORK

advertisement

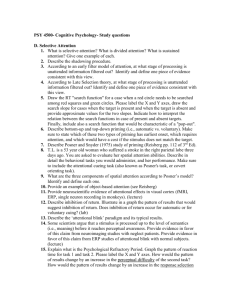

THE DEVELOPMENT OF NEURAL NETWORK RELATED TO ATTENTION AND SELF REGULATION Michael I. Posner and Mary K. Rothbart University of Oregon, Eugene, USA Progress in neuroimaging and in sequencing the human genome make it possible to think about neural networks in terms of experiential and genetic factors that shape their development. In this paper we use both of these these methods to explore the development of attentional neworks. Attentional Networks Three major functions of the attention system are: achieving and maintaining the alert state, orienting to sensory events and voluntary control of responses (Posner & Fan, in press). While all humans have an attention system, the efficiency of its operation clearly differs between people. We have carried out an extensive series of investigations on an attentional network related to self regulation of cognition and emotion (Bush, Luu & Posner, 2000). We have developed the Attention Network Test (ANT) to assay the efficiency of this and other attentional networks (Fan et al 2002). The ANT relies on the flanker task to provide evidence of conflict and uses cues to induce different states of orienting and alerting. Imaging studies of adults demonstrate that the three functions are carried out by separate anatomical networks, and imaging also shows that a number of conflict related tasks that can be run with children have common activations in the anterior cingulate and lateral prefrontal areas. We also have developed a child ANT, with particular interest in studying the executive attention network , related both to self regulation and the ability to resolve conflict. Using the Child ANT and related tests we found that the executive attention network develops between age 2 and 7 years, but remains constant after that (Rueda et all, 2004). Temperament Cognitive measures of conflict resolution in these laboratory tasks have also been linked to aspects of children's temperament. Children better able to resolve conflict received higher parental ratings of effortful control (Gerardi-Caulton, 2000). We regard effortful control as reflecting the efficiency with which the executive attention network operates in naturalistic settings. In adolescents effortful control and the ability to resolve conflict are protective factors for the development of antisocial behavior. Thus laboratory studies of an individual’s ability to resolve conflict provide an important clue to the likely difficulty of successful socialization, and also make it possible to use questionnaires measuring effortful control to better understand how different cultures seek to use attentional networks to build control systems for their children (Rothbart, Ahadi & Hershey, 1994). Genetic Studies Individual differences in effortful control and in the ability to resolve conflict are highly heritable (Fan et al, 2001) We have used the Attention Network Test and the association of its networks with particular neuromodulators to discover two dopamine genes related to performance in resolving conflict (Fossella et al 2002). A neuroimaging experiment compared persons, with different alleles of these conflict related genes while they performed the ANT (Fan et al 2003). We found that these alleles produced different degrees of activation within the anterior cingulate (Fan et al, 2003), which is a major node of the network involved in the resolution of conflict. Other work has found cholinergic genes are related to the network controlling orienting to sensory events (Marrocco & Davidson, 1998; Parasuraman, in press). The finding that specific genes influence individual differences in orienting to sensory information and resolving conflict suggests that these same genes may be important in building the attentional networks that are common to all of us. One of the genes we found related to executive attention has also been implicated in attention deficit disorder, and when it is knocked out, mice display a deficit in their ability to explore their environment. Training Genes influence the networks underlying human brain function only in conjunction with experience. It is a good test of our understanding of how experience influences these networks to determine if we can design effective training of attention. There is evidence that attention training can be effective in recovery from brain injury and in assisting those with developmental attention deficits to overcome them. A central aspect of the executive attention network is the ability to deal with conflict. We used this feature to design a set of training exercises for children, adapted from efforts to train macaque monkeys who would be sent into outer space. We began to test the efficacy of a very brief five days of attention training with groups of normal 4-yearold children. We found some evidence that this training produces more adult like performance, although the highly variable RTs of four year olds made it difficult to interpret the behavioral data. The EEG data showed that four year olds after attentional training showed the N2 differences between congruent and incongruent trials found in adults. We also found significant generalization in IQ scores in the trained group in comparison with an untrained control. Because of the very brief nature of the training we did not expect to find substantial improvements, so the outcome is very encouraging for additional research based upon more substantial training. This is only the start of what we hope will become an effort to see if attention training at critical times in development can shape and improve brain networks. This work has obvious implications for the development of preschool curricula. As the number of children who undergo our training increases, we can examine aspects of their temperament and genotype to help us understand who might benefit from attention training. Psychopathology Many neurological and psychiatric disorders have been said to involve pathologies of attention. Without a real understanding of the neural substrates of attention, this has been a somewhat empty classification. This situation is changed with the systematic application of our understanding of attentional networks to pathological issues. Only a few pathologies have been studied by methods which allow us to state which of the attention networks are affected. More commonly one or another of the attentional networks has been examined in isolation. We discuss in this paper applications to Aging and Alzheimer’s Disorder, ADHD, Autism, Borderline Personality Disorder, Neglect, and Schizophrenia Overall we emphasize how neuroimaging and gentics provides new insight into the role of attentional networks in human behavior. We believe these new methods, and our effort to integrate them, have importance for all areas of cognitive science and can be used with the many networks now shown to underlie aspects of human cognition and emotion. References: Bush, G., Luu, P. & Posner, M.I. (2000). Cognitive and emotional influences in the anterior cingulate cortex. Trends in Cognitive Science, 4/6:215-222. Fan, J., Flombaum, J.I., McCandliss, B.D., Thomas, K.M. & Posner, M.I (2002). Cognitive and brain mechanisms of conflict. Neuroimage, 18:42-57. Fan, J., Fossella, J.A., Summer T. & Posner, M.I. (2003). Mapping the genetic variation of executive attention onto brain activity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA, 100:7406-11. Fan, J., McCandliss, B.D., Sommer, T., Raz, M. & Posner, M.I. (2002). Testing the efficiency and independence of attentional networks. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, (3)14:340-347. Gerardi-Caulton, G. (2000). Sensitivity to spatial conflict and the development of self-regulation in children 24-36 months of age. Developmental Science, 3/4:397-404. Fan, J., Wu, Y., Fossella, J. & Posner, M.I. (2001). Assessing the heritability of attentional networks. BioMed Central Neuroscience, 2:14. Fossella, J., Sommer T., Fan, J., Wu ,Y., Swanson, J.M., Pfaff, D.W. & Posner, M.I. (2002). Assessing the molecular genetics of attention networks. BMC Neuroscience, 3:14. Marrocco, R.T. & Davidson, M.C. (1998). Neurochemistry of attention. In R. Parasuraman (Ed.), The Attention Brain (pp. 35-50). Cambridge, Mass:MIT Press. Parasuraman, R. (in press) Molecular Genetics of Visuospatial Attention and Working Memory In Posner, M.I. (ed) Cognitive Neuroscience of Attention New York: Guildford Press Posner, M.I. & Fan, J. (In press). Attention as an organ system. To appear in J. Pomerantz (Ed.), Neurobiology of Perception and Communication: From Synapse to Society. The IVth De Lange Conference. Cambridge UK:Cambridge University Press. Rothbart, M. K., Ahadi, S. A. & Hershey, K. (1994). Temperament and social behavior in children. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 40:21-39. Rueda, M.R., Fan, J., McCandliss, B., Halparin, J.D., Gruber, D.B., Pappert, L. & Posner, M.I. (2004). Development of attentional networks in childhood. Neuropsychologia. 42, 1029-1040