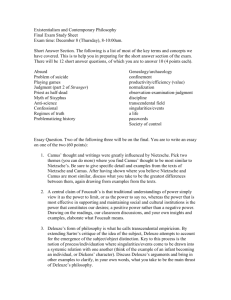

Sensation and Sensibility: Deleuze`s Aesthetic Metaphysics

advertisement

Sensation and Sensibility: Deleuze’s Aesthetic Metaphysics In the fourth chapter of Difference and Repetition, Deleuze remarks that, “Difference is not diversity. Diversity is given, but difference is that by which the given is given, that by which the given is given as diverse. Difference is not phenomenon but the noumenon closest to the phenomenon.”1 From the standpoint of an empiricism often attributed to Deleuze,2 this declaration cannot but appear startling. This remark, which is not at all isolated in Deleuze’s thought, suggests that difference, far from being equated with the actuality of what is given as Bruce Baugh would have it,3 is instead that which accounts for the actuality of the thing. In short, difference is the principle by which the given is given or produced, and not the given itself. If this claim is startling from the point of view of empiricism, then it is because it completely undermines the central tenant of classical empiricist thought. In its most basic essence, empiricism is a thesis about the origins of our knowledge and ideas. Hume expresses this point with great clarity in A Treatise Concerning Human Nature, when he remarks that “…we shall content ourselves with establishing one general proposition, That all our simple ideas in their first appearance are deriv’d from simple impressions, which are correspondent to them, and which they exactly represent.”4 Now, the 1 Gilles Deleuze, Difference and Repetition, pg. 222. Hereafter DR. Cf. Bruce Baugh’s French Hegel: From Surrealism to Postmodernism (2003), Patrick Hayden’s Multiplicity and Becoming: The Pluralist Empiricism of Gilles Deleuze (1998), and John Mark’s Gilles Deleuze: Vitalism and Multiplicity (1998). 3 For instance, Baugh remarks that “Empirical actuality, then, is not to be explained through possibility, however “concretely” determined, but only through empirical causes which contain no more and no less reality than their effects, and are immanent in their effects, as Spinoza’s God is entirely immanennt in his attributes. Instead of being explicable through the concept, empirical actuality, “difference without concept… [is] expressed in the power belonging to the existent, a stubbornness of the existent in intuition”. Like classical empiricists, Deleuze locates this intuition in sensory consciousness, a receptivity which grasps what comes to thought from outside” (Baugh 2003, 150). The problem with this view is that both Hegel and Kant both already accept it. Both thinkers are agreed that there is a stubbornness of the actuality of sensation that is outside the concept. As we shall see, Deleuze’s strategy will be to undermine the passivity of receptivity of intuition at the outset, demonstrating that sensibility already possesses an intelligibility of its own that is not in need of conceptual supplementation. 4 David Hume, A Treatise Concerning Human Nature, Oxford: The Clarendon Press, 1978, pg. 4. 2 impressions of which Hume here speaks are exactly what Deleuze has in mind when he refers to the diverse given through which the given is given as given. It is in this respect that classical empiricism is a philosophy of origins, for the thesis of empiricism is that beneath these impressions of sense experience, there is nothing else to be known. The impressions of sense experience are the sine qua non of knowledge, or the ultimate foundation of all knowledge. Beyond these sense-impressions and the relations that are drawn between them through the work of association, there is nothing more to know. However, if difference is not diversity, if difference is not that which is given but rather that through which the given is given as diverse, it then follows that Deleuze has departed substantially from the position described by classical empiricism. For, according to the classical empiricist, the litmus test as to whether something is admissible or not admissible within the realm of knowledge revolves around the issue of whether it can be traced back to the sensible given. Yet in evoking the principle by which the given is given and treating it as the noumenon closest to the phenomenon, Deleuze has abandoned this litmus test altogether.5 Deleuze thus cannot be described as an empiricist in the classical sense, nor can his position properly be thought as an epistemology. In light of the foregoing, we can safely say that Deleuze is not so much tracing all thought and knowledge back to its origin in sense-experience or impressions as was the case with Hume and other empiricists, as he is trying to account for the genesis of 5 We see here why the being of the sensible and the sensible must be rigorously distinguished from one another in Deleuze’s thought. Bruce Baugh equates the being of the sensible with the actuality of the sensible given that is a sort of brute existent, but for Deleuze the being of the sensible is not the sensible itself, but that which is the productive or genetic principle of the sensible. As Deleuze remarks in contrast to Baugh, “The object of encounter… really gives rise to sensibility with regard to a given sense… It is not a quality but a sign. It is not a sensible being but the being of the sensible. It is not the given but that by which the given is given. It is therefore in a certain sense the imperceptible” (DR, 139-140). This passage ought to be enough to distinguish between what Bergson referred to as intuition and empirical sensibility. The being of the sensible is not the actuality of the sensed data, but its sufficient reason. sensibility itself. As Deleuze remarks in the chapter entitled “Repetition for Itself” in Difference and Repetition, The first beyond [of the pleasure principle] already constitutes a kind of Transcendental Aesthetic. If this aesthetic appears more profound to us than that of Kant, it is for the following reasons: Kant defines the passive self in terms of simple receptivity, thereby assuming sensations already formed, then merely relating these to the a priori forms of their representation which are determined as space and time. In this manner, not only does he unify the passive self by ruling out the possibility of composing space step by step, not only does he deprive this passive self of all power of synthesis (synthesis being reserved for activity), but moreover he cuts the Aesthetic into two parts: the objective element of sensation guaranteed by space and the subjective element which is incarnate in pleasure and pain. The aim of the preceding analysis, on the contrary, has been to show that receptivity must be defined in terms of the formation of local selves or egos, in terms of the passive syntheses of contemplation or contraction, thereby accounting simultaneously for the possibility of experiencing sensations, the power of reproducing them and the value that pleasure assumes as a principle. (DR, 98) As this passage demonstrates, contrary to Baugh’s reading that holds that for Deleuze sensation is the ultimate ground of metaphysics, sensation is itself something that must be accounted for. The problem with classical empiricism and Kant, according to Deleuze, is that it assumes receptivity already has a constituted form and is therefore dogmatic. In contrast to this position, Deleuze seeks a genesis of the “sensibility of sense”, which also opens the possibility that sensations themselves are the result of this genesis and that an infinite number of different sensibilities or forms of receptivity are possible. It is for this reason that Deleuze’s aesthetic is a properly transcendental aesthetic, and not simply a representation of judgments made about art. What is at stake here is not simply the givens of experience, but how these givens come to be given. The term aisthesis has two connotations: On the one hand it refers to the beautiful and art, to judgments we make pertaining to art, while on the other it refers to feeling or sensibility. A transcendental aesthetic would refer to the a priori of sensibility, to its conditions of production. In this regard, Deleuze, unlike Baugh, mitigates strongly against the view that sensibility is defined solely in terms of simple receptivity. Rather, the “receptive-ability” of receptivity must itself be accounted for. My ability to receive must be given a transcendental account. As we shall see, it is not the actuality of the given in sensation that evades the conceptualism of Kant and Hegel-- how could it, given that it was the premise of the brute actuality of the given that led both Kant and Hegel to argue that sensible experience must be supplemented by the concept?6--but rather it is the genesis of sensibility itself that allows Deleuze to escape Kant and Hegel. As Deleuze puts it, “The passive self is not defined simply by receptivity-- that is, by means of the capacity to experience sensations --but by virtue of the contractile contemplation which constitutes the organism itself before it constitutes sensations” (DR, 78). There is thus a two-fold genesis of sensation that must be accounted for. On the one hand, Deleuze seeks to account for the production of the quality found in sensation, while on the other he seeks to account for the particular faculty of sensibility itself. Following Augustine,7 we are always able to In short, Kant and Hegel already accept Hume’s thesis that the sensible is composed of brute sensations that have the mark of actuality and which are irreducible. This point can be seen in Kant in his treatment of the manifold of sensibility, and in Hegel in the chapter on Sense-Certainty in The Phenomenology of Spirit. What is at issue in both thinkers is how relations of necessity are established between these sensations. Baugh’s thesis has the air of stubbornly insisting on the position of classical empiricism, without responding to the arguments advanced against this position by Kant and Hegel. It is my view that Deleuze both accepts these criticisms and seeks to surpass the conceptualism of their positions by seeking to locate intelligibility in the given itself through a genetic account of the sensibility of sense. In this regard, Deleuze’s position is closer to Leibnizian rationalism than classical empiricism, though he indeed owes a great debt to Hume. 7 Aurelius Augustine, On the Free Choice of the Will, in Philosophic Classics: Medieval Philosophy, Volume II, Baird and Kaufmann, eds., pg. 78. “This much is proven: Corporeal objects are perceived by the senses of the body; a sense cannot perceive itself; moreover, by means of the inner sense, corporeal objects are perceived through the senses of the body, and the senses of the body themselves are also perceived by the inner sense; but by means of reason, all these things, and reason itself, become known and are included in knowledge.” What is new in Deleuze is that he attempts to simultaneously account for the production of both the subject (the faculty of sensing) and the object (that which is sensed), arguing that the object cannot properly be said to pre-exist this genesis. Here Deleuze shows the manner in which he’s been influenced by Kantian German Idealism. However, where Kant saw this production of the object 6 distinguish between the faculty that receives the sensation, the quality or object that is received in the sensation, and the awareness that one is aware of this sensation, even though the three emerge together in one and the same genesis. This distinction perfectly mirrors Deleuze’s distinction between the passive contemplative selves that contract a difference and produce a quality. Thus, for instance, there is both a genesis of the bat’s faculty for receiving sonar information and the qualitative feels of this information. We thus see why Deleuze’s position is properly a transcendental empiricism and not simply an empiricism. Although Deleuze often simply refers to himself as an empiricist (just as often referring to his position as a superior empiricism, which should give us pause), his real aim is not the epistemological project of grounding everything in experience, but of accounting for the conditions of sensible experience. In describing this position, Deleuze remarks that, We have contrasted representation with a different kind of formation. The elementary concepts of representation are the categories defined as the conditions of possible experience. These, however, are too general or too large for the real. The net is so loose that the largest fish pass through. No wonder, then, that aesthetics should be divided into two irreducible domains: that of the theory of the sensible which captures only the real’s conformity with possible experience; and that of the theory of the beautiful, which deals with the reality of the real in so far as it is thought. Everything changes once we determine the conditions of real experience, which are not larger than the conditioned and which differ in kind from the categories. The two senses of the aesthetic become one, to the point where the being of the sensible reveals itself in the work of art, while at the same time the work of art appears as experimentation. (DR, 68) We have seen why there is a relationship between the two senses of the aesthetic and the theory of the sensible. If the theory of the sensible is to account for the production of taking place through the synthesis of concepts and intuitions, Deleuze attempts to develop this account at the level of sensibility itself. We also see how Deleuze differs from Hegel here. Where Hegel treats substance and subject as two domains that are opposed to one another and in need of dialectical reconciliation, Deleuze instead attempts to account for the “flowering” of substance and subject through a genetic actualization. sensibility itself, then this production is an aesthetic creation just as the work of art is a creation. The artist does not simply produce a fiction or semblance of the world, but rather produces a new way of sensing the world, a new form of sensibility. We can see something similar at work in evolutionary biology. The evolution of a new species isn’t simply the evolution of a new organism or body, but also the evolution of both a new form of sensibility, a new way of sensing the world, and the differentiation of a new environment. The snake and the tortoise might very well exist in the same spatial region of the universe, but nonetheless have entirely different umwelts or environments structured according to the system of relevancies pertaining to their specific organism. These worlds are the result of a genesis, which implies that we always speak poorly when we suggest that the organism adapts to an environment, in that the environment itself is also engendered along with the organism. The production of the umwelt is itself akin to a work of art in that it differentiates fields of intensity within the world as being relevant and irrelevant. Here Deleuze’s conception of aesthetics is far closer to Nietzsche’s in The Birth of Tragedy, than Kant’s in The Critique of Judgment. What is at stake is not judgments about the beautiful or judgments of taste, but rather the production of the work of art itself. In this regard, beings themselves have come to be seen as an aesthetic production. For Deleuze it is not simply the organism that produces the ability to receive the object that already exists, but rather the object is produced simultaneously with the subject. On the other hand, this project of reconciling the two sundered halves of the aesthetic is closely related to the project of giving an account of the conditions of real rather than all possible experience. According to Deleuze, the problem with thought like that of Kant’s and Hegel’s is that it fails to reach the thing itself in that it thinks in terms of abstract categories or the conditions for all possible experience, rather than the conditions of real experience. I shall have more to say about this problem in a moment, but for now we must determine what Deleuze has in mind by real experience as opposed to possible experience. In his early essay, “Bergson’s Conception of Difference”, Deleuze remarks that, “If philosophy has a positive and direct relation to things, it is only insofar as philosophy claims to grasp the thing itself, according to what it is, in its difference from everything it is not, in other words, in its internal difference” (Deleuze 2004, 32). It is the individuality of the thing itself that must be accounted for. In short, the concept must be able to go all the way to the thing itself without remainder; or, as Deleuze claims, the concept must be identical to the thing. However, it would be a mistake to suppose that the thing itself is sufficient to account for itself. If Deleuze’s philosophy is an empiricism then it is because the thing is contingent and cannot be deduced and must therefore be found in experience, but it is nonetheless a transcendental philosophy which seeks to account for the being of this thing. The thing itself, its actuality as this thing here, is not itself sufficient. If the thing itself is not sufficient, then this is because the actuality of the thing blinds us to its conditions of production. On the one hand, Deleuze, following Bergson, attributes thinking in terms of the actualized thing as being the origin of all the distortions of representation.8 As Deleuze remarks in his article on Bergson, This point is important for it suggests that what Deleuze refers to as the “image of thought” in the third chapter of Difference and Repetition isn’t simply a mistake or error that could be avoided, but that it has the status of what Kant calls a “transcendental illusion” or unavoidable illusions of reason, and is produced internal to being itself. In seeking to account for the individuality of the thing, Deleuze is also under the obligation to give us an account of the genesis of these sorts of illusions. 8 Things, products, results are always composite…Space only ever presents, and the intelligence only ever discovers, composites, e.g. the closed and the open, geometric order and vital order, perception and affection, perception and recollection, etc. And one must understand that a composite is undoubtedly a blending of tendencies that differ in nature, but as such is a state of things in which it is impossible to make out any difference of nature. A composite is what one sees from that point of view where nothing differs in nature from anything else. The homogeneous is by definition composite, because what is simple is always something that differs in nature: only tendencies are simple, pure. That which really differs, therefore, can be found only by rediscovering the tendency beyond its product. (Deleuze 2004, 35).9 Thus, while it is the thing itself that is to be accounted for, we fall into error if we remain with the actualized thing.10 That is, we fall into thinking in terms of identity, treating everything as differing in degree from everything else, failing to get at the individuating or internal difference of the thing. On the other hand, it is the individuating difference that is sought in the thing, not the thing itself. The thing itself is a launching point into an analysis of its genetic conditions. Deleuze expresses this point very clearly in a short 9 It bears noting that while Deleuze ultimately seeks the reason of this thing here itself, his position nonetheless avoids falling into a nominalism or the belief that only individual things exist. As Deleuze remarks in “Bergson’s Conception of Difference”, “Either we extract the abstract and general idea of color, and we do so by “effacing from red what makes it red, from blue what makes it blue, and from green what makes it green”: then we are left with a concept which is a genre, and many objects for one concept. The concept and the object are two things, and the relation of the object to the concept is one of subsumption. Thus we get no farther than spatial distinctions, a state of difference that is external to the thing. Or we send the colors through a convergent lense that concentrates them on the same point: what we have then is “pure white light,” the very light that “makes the differences come out between the shades.” So the different colors are no longer objects under a concept, but nuances or degrees of the concept itself. Degrees of difference itself, and not differences of degree. The relation is no longer one of subsumption, but one of participation. White light is still a universal, but a concrete universal, which gives us an understanding of the particular because it is the far end of the particular. Because things have become nuances or degrees of the concept, the concept itself has become a thing. It is a universal thing, if you like, since the objects look like so many degrees, but a concrete thing, not a genus or generality. Properly speaking, there is no longer many objects for one concept; the concept is identical to the thing itself” (Deleuze 2004, 43). Like modes which are modes of attributes, the thing itself is thus a singular inflection of the concrete universal and not a nominal individual. 10 Alain Badiou has expressed this point well in Deleuze: The Clamor of Being, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2000, pg. 15. “…One starts to go wrong as soon as one imagines that the constraint exercised by concrete cases makes Deleuze’s thought a huge description of collection of the diversity characterizing the contemporary world. For one presumes then that the operation consists in thinking the case. This is not so: the case is never an object for thought; rather, intrinsic to the destination that, ultimate automatic, is thought’s own, intrinsic to the exercising ‘to the very end’ of thought’s power, the case is what forces thought and renders it impersonal.” This follows as a consequence of Deleuze’s claim that difference is not diversity or the given. essay on the work of Gilbert Simondon who figures heavily in Difference and Repetition. There Deleuze observes that, Traditionally, the principle of individuation is modeled on a completed individual, one who is already formed. The question being asked is merely what constitutes the individuality of this being, that is to say, what characterizes an already individuated-being. And because we put the individual after the individuation, in the same breath we put the principle of individuation before the process of becoming an individual, beyond the individuation itself… In reality, the individual can only be contemporaneous with individuation, and individuation, contemporaneous with the principle: the principle must be truly genetic, and not simply a principle of reflection. Also, the individual is not just a result, but an environment of individuation. (Deleuze 2004, 86) We see here exactly the same problem that Bergson denounces of beginning with the actuality of the thing, of ignoring the conditions for the production of the thing. The standpoint of representation begins with the concrete case or individual thing and then asks in reflection how it individuates this thing from another thing in the concept of the thing. In this way it makes the principle of individuation a principle of reflection or an operation that takes place in what Deleuze calls the active synthesis of cognition. As a result, the principle of individuation comes to be treated as external to the thing itself, rather than being treated as an internal principle. The principle of individuation here seeks to represent the thing, rather than give the conditions under which the thing is individuated or produced. Now, as interesting as all this sounds, we must ask why it is necessary. Is it reasonable to ask for a principle of individuation that goes all the way to the thing itself, that coincides with the thing itself? What philosophical problem is Deleuze here responding to? Why, for instance, should we be troubled by the division of concepts and intuitions that underlies Kant’s transcendental idealism? Does not Kant manage to establish necessity for causal claims and therefore avoid falling into skepticism? While it is indeed the case that Kant manages to establish the necessity of causal relations by treating them as a priori concepts of the understanding and by positing space and time as a priori forms of intuition, there is still the further problem of how these categories can be applied to empirical experience in a non-arbitrary fashion. The problem arises with respect to a distinction Kant wishes to draw between judgments of perception and judgments of experience in the Prolegomena.11 Between a judgment of perception in which I claim the sun shines and the stone grows warm, I have only produced an association which fails to establish the necessity we attribute to causal claims. I have related one event to another event, but have not asserted that given any events of this type at any particular time and space, this relation will occur. By contrast, when I apply the category of causality to the relationship between these two events, I have now made an assertion of necessity that therefore transforms the subjective and associative relation into an objective and necessary relation. However, what is it that determines how to apply this particular category to these particular things? If the application of the a priori categories of the understanding is an act of intellect, what is to prevent me from applying them in whatever way I might please? For instance, if someone states, “I curse my mother and my house burns down” is applying the category of causality to the relationship between these two events sufficient to establish the objective validity of this proposition? Through the application of this category, has one established that the relationship between these two events is one of necessity? 11 Immanuel Kant, Philosophy of Material Nature, Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company, Inc, 1985, pg. 44. “…when the sun shines on the stone, it grows warm. This judgment, however often I and other may have perceived it, is a mere judgment of perception and contains no necessity; perceptions are only usually conjoined in this manner. But if I say: the sun warms the stone, I add to the perception a concept of the understanding, viz., that of cause, which necessarily connects with the concept of sunshine that of heat, and the synthetic judgment becomes of necessity universally valid, viz., objective, and is converted from a perception into experience.” It would seem that the category alone is insufficient for establishing the necessity of the relationship between two events. Between the concept and the intuition there is always a gap that leaves unexplained how the category is to be applied to this specific case. It is precisely this problem that Deleuze has in mind when he remarks that the claws of possibility are too broad. Kant too recognizes this problem with respect to the schematism of the understanding. If the schematism is necessary in The Critique of Pure Reason, then this is because there must necessarily be a third term to mediate between the abstract concept denoting a possibility and the singular instance in intuition to which this concept is applied. Yet the schematism, as a conceptual determination of time, seems to only beg the question and exacerbate the problem, rather than truly solving it. For the whole question was that of how we’re to apply concepts to intuitions (particulars in time and space). If we argue that this is possible because we possess, a priori, conceptual determinations of time that mediate between sensible particulars and general concepts, we still haven’t explained how conceptual determinations of time are possible. Deleuze refers to precisely this problem when speaking about the duality between concepts and intuitions in Kant.12 There is thus a tremendous problem at the center of Kant’s impressive machinery, that still fails to reach the thing itself. Rather than giving an account of the thing itself, Kant remains external to the thing in such a way that his account of necessary propositions is necessarily arbitrary and contingent. As Deleuze remarks, “Such a duality refers us back to the extrinsic criterion of constructibility and leaves us with an external relation between the determinable (Kantian space as a pure given) and the determination (the concept in so far as it is thought). That the one should be adapted to the other by the intermediary of the schematism only reinforces the paradox introduced into the doctrine of the faculties by the notion of a purely external harmony: whence the reduction of the transcendental instance to a simple conditioning and the renunciation of any genetic requirement. In Kant, therefore, difference remains external and as such empirical and impure, suspended outside the construction ‘between’ the determinable intuition and the determinant concept” (DR, 173). 12 Why, then, is Kant led into this problem? What assumption is at work that leads Kant to such an external point of view with respect to the relationship between concepts and intuitions? If this is a problem, then it arises precisely from treating sensations as brute givens received on the basis of an already constituted receptivity that has no synthetic power of its own. When we treat sensation in spatialized terms as arrayed side by side with one another, we are able to discern nothing but contingent relations between sensations. However, when we attribute a synthetic power to receptivity itself, when we give both a genetic account of the faculty of receptivity and the sensation that accompanies receptivity, three things follow: Not only do we overcome the opposition between concepts and intuitions, discovering an internal relation where before there was only an external relation, we are now able to locate intelligibility in the sensible itself as the being of the sensible and discern a corresponding production of objects corresponding to this genesis. Deleuze describes an example of such a genesis in contrast to Kant’s account of conceptual conditioning, in relation to the post-Kantian Idealist Solomon Maimon. In order to understand better the alternative offered by Maimon, let us return to a famous example: the straight line is the shortest path. ‘Shortest’ may be understood in two ways: from the point of view of conditioning, as a schema of the imagination which determines space in accordance with the concept (the straight line defined as that which in all parts may be superimposed upon itself)-in this case the difference remains external, incarnated in a rule of construction which is established ‘between’ the concept and intuition. Alternatively, from the genetic point of view, the shortest may be understood as an Idea which overcomes the duality of concept and intuition, interiorises the difference between straight and curved, and expresses this internal difference in the form of reciprocal determination and in the minimal conditions of an integral. The shortest is not a schema but an Idea; or it is an ideal schema no longer the schema of a concept. (DR, 174) What we have here is a genetic account of the production of a quality or a sensation in the form of a sensation. However, what is more, this sensation is not simply a brute and chaotic being with no necessity, but rather through the differential nature of this quality, it has the necessity and intelligibility that belongs to the quality of the “shortest”. The sensation of the shortest is itself sufficient and is in no need of conceptual supplementation; or rather, it is a lived necessity rather than a thought necessity. In this way Deleuze has responded to both Hume’s skepticism and Kant’s demand for necessity, at the level of sensibility itself, which is why he claims that through transcendental empiricism aesthetics becomes an apodictic discipline. Deleuze has many names for what he here refers to as an Idea. The concept of Idea can be equated with what Deleuze refers to as Problems, Multiplicities, and the differential relation dy/dx. The important point is that an Idea, for Deleuze, is not a mental image in the mind. Rather, like Plato, the Idea has an ontological status of its own. However, where in Plato Ideas are transcendent to the world of appearances, in Deleuze these Ideas are immanent to the world of the given and are that by which the given is given. They are the genetic conditions of experience. These Ideas do not represent things, but are the forces through which the thing is produced. And indeed, in that they share a special relationship to the differential, they are able to go all the way to the thing itself without remainder, while also being able to account for variations in the thing such as the variations of a triangle undergoing topological mutations while still remaining a triangle. It is in this way that Deleuze is able to overcome the gap between concepts and intuitions, reach the thing itself, and proudly claim that, “…the condition must be a condition of real experience, not of possible experience. It forms an intrinsic genesis, not an extreme conditioning. In every respect, true is a matter of production, not of adequation” (DR, 154). However, these truths are not the arbitrary truths of whim, but contain a necessity and intelligibility all their own, guaranteed by the differential relations of being. In short, Deleuze’s response to Kant and Hegel is not a return to classical empiricism or the primacy of the actual in sense-experience, but to argue that experience itself is the result of a genesis that is both creative and open, and which contains its own necessity.