Feminine Sancitity in Medieval Wales

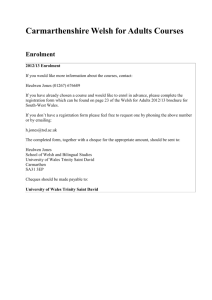

advertisement

Jane Cartwright, Feminine Sancitity and Spirituality in Medieval Wales, University of Wales Press, Cardiff, 2008. £75.00, ISBN 978-0-7083-1999-4 (cloth), pp. xv + 301. Illustrations. Reviewed by: Kimm Curran, Faculty of Education, University of Glasgow, December 2009. Jane Cartwright's work on female sanctity in medieval Wales is well known to many. For the first time, Cartwright's work has been collected together to form a substantial piece of work on the universal female saints in Wales, native Welsh female saints and female religious from the fifth century until the mid-sixteenth. These pieces have, by and large, been unavailble to non-Welsh speaking audiences and for those interested in female sanctity in Wales it is refreshing to find all of this work in one place. This reader, who collected these pieces in Welsh and English over the years, is thankful for this volume. Cartwright sets out to cover all aspects of feminine sanctity in medieval Wales by looking at saints, holy women and nuns. She puts Wales into a wider European contect by addressing how universal female saints were revered in Wales but also puts these saints in the context of Wales and the worship of these saints on the ground. Her collection is divided into roughly three parts: Native Welsh saint cults, universal saints and nunneries but she also addresses the experience of noble women and the worship of these female saints in Wales. Chapter 1 focuses on the cult of the Virgin Mary and how she was viewed in Middle Welsh texts. The Virgin Mary was one of the more popular saints in medieval Wales and there is a long corpus venerating her, most especially texts from the twelfth to fifteenth centuries. Her conception, birth, role within Christianity and relationship with Joseph is emphasised by the Welsh poets and Cartwright argues that the popularity of Marion devotion ties Wales to wider Christendom. Female native saints of Wales are the emphasis for chapter 2 and there is a brief outline of the historiography of these saints and the gender assumptions made by historians. In most hagiography of female saints the prerequisite for female sanctity was virginity, a refusal to marry, living alone or with a community of females but these women become the objects of male desire and are abducted, threatened with rape or forced marriage, tortured and decapitatied; native female Welsh saints share this common trait with their Continental counterparts (86). Concluding this chapter, Cartwright shows that female saints were more numerous than previously claimed and revered in Wales for a number of reasons. However, the assumption that because there were a generous proportion of revered females saints means a 'favourable environment for female religious' was not the case (see chapter 6). In chapter 3, Cartwright dives further into the theme of the virginity of female saints and highlights that this trait did not have the same status or meaning in medieval Wales as elsewhere. She provides us with the case study of St Non, mother of St David, who was raped, became pregnant and gave birth; she was not a virgin but a mother. Unfortunately, there is no surviving vitae for St Non and we gleen what we can of her account through the vitae of her son, St David. Despite St Non being a mother rather than a virgin saint, she was popular throughout Wales, Brittany. Indeed, Cartwright argues that mother saints were more common in Wales than on the Continent and further stresses the point that these vitae may have been used by the laity. This lack of emphasis on virginity carries over into Middle Welsh lives of so-called foreign saints, such as Saints Mary Magdelene and Martha discussed in Chapter 4. The vitae of Mary and Martha were translated into Middle Welsh some time before the midfourteenth century. Cartwright argues that these saints lives were more than likely read or heard and appreciated by laywomen rather than religious (124). Cartwright emphasises this by presenting a list of evidence of manuscripts with Welsh lives of female saints as well as those with Mary Magdelene and Martha which gives us an appreciation of the Welsh material on the subject. Further to this, she follows this by showing how the legends of Mary and Martha developed on the Continent and in Wales in particular. She ends this chapter by addressing the other sources for these saints in Wales: poetry, church dedications, holy wells and visual representations. The aim of this chapter is to show the importance of these religous texts within a lay context and she continues this discussion in chapter 5 where she looks at St Katherine. The Cult of St Katherine of Alexandria in Wales became popular in the fourteenth century as it did elsewhere in Europe and Cartwright argues that this cult was more than likely unheard of in Wales until this time. This chapter provides an overview of the cult and looks at as many Welsh sources as possible. Cartwright emphasises that the cult of St Katherine in Wales indicates that Wales was not a 'culturally isolated land' but rather an 'integrated member of wider cultural currents ...across the whole of Christendom' (150). Cartwright then presents us with examples of St Katherine's visual representation in or at churches, in rings and seals and tomb panels. St Katherine is further discussed in church dedications and then the Middle Welsh life. These last two chapters strongly suggest that these three saints vitae were for lay audiences: Martha stresses the good hostess and generousity; Magdalene centres on the lay family, childbirth, healing and domestic settings; Katherine highlights widsom, faith and chastity. This, Cartwright argues, is evidence for both an audience of laywomen, and the diminished interest in women’s virginity. The last chapter turns to the medieval convents of Wales and Cartwright gives us a brief glimpse of the three convent of Wales, their foundation, documentary and the literary evidence that survives. It suggest why there were so few convents in Wales during this period. All three houses were founded in the twelfth century and can generally be attributed to Lord Rhys, Maredudd ap Rhobert and Roger de Clare. The paucity of sources for female religous has hindered the study of female but in the case for Wales, the paucity of sources also impedes our understanding of the finances, prosperity and inhabitants more generally. However, Cartwright looks at Welsh poems to nuns to give us a wider understanding of their signficance in Wales. The Bardic Grammars, for example, suggest how a nun should be praised for her holiness and pure way of life 'but difference exists between Welsh poetry to nuns and to men of the church' (188) and nuns were to be persuaded to end their monastic lifestyle. Arguments of why there were so few convents in Wales are suggested: 'women were encouraged to lead chaste but not celiabate lives within marriage'; complex Welsh law regarding virginity and land; and patronage towards parish churches rather than convents (202-5) but these reasons are speculative at best. The arguments presented in this collection are strong and well supported by both visual, written and material culture of medieval Wales. Cartwright's command of the Welsh material is commendable and it shows in her maticulous dedication and understanding of the sources. The one question that was not adequately addressed was how the saints vitaes was circulated (if known), who actually read them (gentry or otherwise) and was it the lower classes that tended to understand the power of saints through visual and material culture? One drawback from this collection of essays was its organisation. General themes throughout the work needed a conclusion to draw them all together as each chapter appeared to 'stand alone'--however this is a minor point. Cartwrights collection emphasises that feminine sanctity in Wales should not be understood in isolation but rather in a wider Continental context; and more generally, as an integral component of the church, saints lives and religious life in medieval Wales.