Linguistic Politenes..

advertisement

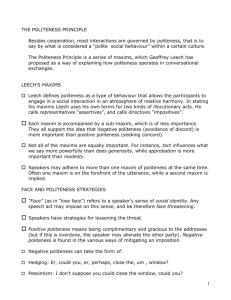

Linguistic Politeness: Brown & Levinson and Leech 1. Politeness as a linguistic universal We maintain that politeness is a linguistic universal by which we mean: 1) Linguistic politeness exists in all languages. 2) Politeness considerations regulate every human speaker’s verbal behavior in social interaction. 2. Face and politeness 1) Goffman’s face notion (1959): “face” is a sacred thing for every human being, an essential factor communicators have to pay attention to, and face wants are reciprocal (if one wants his face cared for, he should care for other people’s face) 2) Brown and Levinson (1978)----the Face Theory A. The theory encompasses both verbal and non-verbal behavior, though most of their discussion concentrates on the former. B. Negative face and positive face: (1) Negative face is the need to be independent, to have freedom of action, and not to be imposed on by others. (2) Positive face is the need to be accepted, even liked by others, to be treated as a member of the same group, and to know that his or her wants are shared by others. C. Five politeness strategies available to speakers to perform a “face-threatening act (FTA)”: (1) bald on record; (2)positive politeness; (3)negative politeness; (4)off-record, and (5)don’t do FTA (ibid:67,73). 1.without redressive action; baldly on record Do the FTA with redressive 2. positive politeness action 4.off record 3.negative politeness 5. Do not do the FTA 3. The politeness principle It may be formulated in a general way from two aspects: to minimize (other things being equal) the expression of impolite beliefs and maximize (other things being equal) the expression of polite beliefs. Leech’s (1983:132) maxims of the politeness principle: 1) Tact Maxim a. Minimize cost to other; b. Maximize benefit to other. 2) Generosity Maxim a. Minimize benefit to self; b. Maximize cost to self. For example, in the following sentences (1) Hand me the newspaper. (2) Got a cigarette? (3) You can use my car. (4) Have another sandwich. We can see that (3) and (4) are more polite than (1) and (2),according to the above maxims. 3) Approbation Maxim a. Minimize dispraise of other; b. Maximize praise of other. 4) Modesty Maxim a. Minimize praise of self; b. Maximize dispraise of self. For example: (5) A: Your performance was outstanding. B: *Yes, wasn’t it! (6) Please accept this small gift as a token of our esteem. *Please accept this large gift as a token of our esteem. (The sentences with “*” are not polite because they have violated the maxims of approbation and modesty.) 5) Agreement Maxim a. Minimize disagreement between self and other; b. Maximize agreement between self and other. 6) Sympathy Maxim a. Minimize antipathy between self and other; b. Maximize sympathy between self and other. For example: (7) A: It was an interesting exhibition, wasn’t it? B: No, it was very uninteresting. (8) A: English is a difficult language. B: True, but the grammar is quite easy. In (7) B makes a quite rude reply, but in (8) B shows politeness by preferring partial disagreement to complete disagreement. 4. Pragmatic scales of politeness Politeness is always a matter of degree. Leech (1983:107-127) set up some pragmatic scales. 1) The cost and benefit scale, on which is measured the cost or benefit of the proposed action to the speaker or the hearer. For example, (9) Peel these potatoes. (10) Hand me the newspaper. (11) Sit down. (12) Look at that. (13) Enjoy your holiday. (14) Have another sandwich. From (9) to (14), these sentences change gradually from cost to the hearer to benefit to the hearer and hence from less polite become more polite to the hearer. 2) The optionality scale, on which speech acts are ordered according to the amount of choice the speaker allows to the hearer. (15) Would you like another sandwich? (16) Have another sandwich. (17) Do have another sandwich. (18) You must have another sandwich. (19) You must finish your work tomorrow. (20) Finish your work tomorrow. (21) Will you finish your work tomorrow? (22) Would you finish your work tomorrow? (23) Could you possibly finish your work tomorrow? 3) The indirectness scale. (24) I order you to answer the phone. (25) Answer the phone. (26) I want you to answer the phone. (27) Will you answer the phone? (28) Can you answer the phone? (29) Would you answer the phone? (30) Would you mind answering the phone? The sentences from (24) to (30) become gradually more indirect as to their “force” manifestation and hence become more polite since the proposed action is a cost to the hearer. 4) Power and solidarity scale, or social-distance scale. It is based on a distinction between power and solidarity made by Brown and Gilman (1960) in their well-known study of personal pronouns.