Chapter 9: The Jovian Planets

advertisement

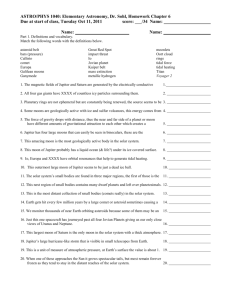

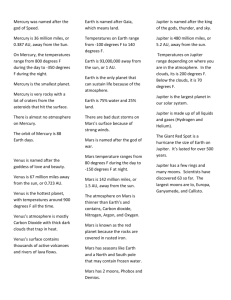

CHAPTER 9 The Jovian Planets CHAPTER OUTLINE 9-1 Jupiter 1. Copernicus deduced that Jupiter was larger than Venus, using the two planets’ relative distances and brightnesses. 2. Galileo observed the angular sizes of Venus and Jupiter and using their relative distances determined that Jupiter is larger. Jupiter as Seen from Earth 1. Jupiter is 318 times more massive than the Earth. It has more than twice the mass of all the other planets, their moons, and the asteroids. 2. Jupiter’s diameter is 11 times that of Earth, and thus its volume is 1,400 times Earth’s. 3. Jupiter’s density is 1.3 g/cm3, only 1/4 of Earth’s. This low density means Jupiter is composed of a higher percentage of light elements. 4. Jupiter is 5.2 AU from the Sun and takes about 12 years to complete one orbit around the Sun. 5. Jovian planets have much greater rotation rates than do terrestrial planets. Jupiter spins on its axis very quickly, once every 9h55m. 6. On Jupiter cloud bands near the equator rotate slightly faster (9h50m) than bands near the poles (9h56m). We say that Jupiter exhibits differential rotation—the rotation of an object in which different parts have different periods of rotation. 7. As a result of its fast rotation and low density, Jupiter is very oblate. Jupiter’s equatorial diameter is 6.5% greater than its polar diameter. Jupiter as Seen from Space 1. In the 1970s the Pioneer and Voyager missions flew by Jupiter and collected thousands of photographs and measurements of charged particles, radiation from the planet, and Jupiter’s magnetic field. 2. Improved data was returned by the spacecraft Galileo that orbited Jupiter and its moons during 1995–2003. It also dropped a probe into the planet’s atmosphere. 3. Unlike terrestrial planets, surface features have little effect on Jupiter’s upper atmosphere, allowing weather patterns to last for long periods. 4. Jupiter’s Great Red Spot, first seen in the mid-1600s, has lasted for over 300 years. It is 40,000 km long and 15,000 km across, larger than the 13,000-km diameter Earth. 5. The red spot is a storm system of rising high-pressure gas whose cloud tops are colder and about 8 km higher than the surrounding regions. It rotates counterclockwise with a period of 6 days. 6. The banded appearance of Jupiter is due to its differential rotation. The standard interpretation of the bands was based on our experience with Earth’s atmosphere: the lightcolored bands mark the tops of low-P, low-T, high-altitude regions of rising gas while the dark-colored bands mark the tops of high-P, high-T, low-altitude regions of sinking gas. 7. Observations from Cassini, en route to Saturn, suggest that this interpretation may be wrong. Almost without exception, individual storm cells of upward-moving bright-white clouds exist in the dark-colored bands. This suggests that these bands are the regions of net upward-moving gas motion (the opposite of the standard interpretation). 8. Data from Voyager showed that at the boundaries of each band, the wind velocities are different and in opposite directions. Data from Galileo support the idea that lighting storms beneath the upper cloud cover are the energy source for Jupiter’s weather patterns. The Composition of Jupiter’s Atmosphere 1. The Galileo probe showed that Jupiter is (by number) about 90% hydrogen, 10% helium, with small amounts of water (H2O), methane (CH4), and ammonia (NH3). This is similar to the composition of the original solar nebula. 2. The Galileo probe found that Jupiter has the same helium content as the Sun’s outer layers but only 10% of its neon concentration. It is possible there is a helium rain in Jupiter’s atmosphere, with neon dissolving in it. 3. The concentration of deuterium was found to be similar to that of the Sun but very different from that of comets or of Earth’s oceans. This minimizes the possible effect of comets on the composition of Jupiter’s atmosphere. 4. The Galileo probe also found that the concentrations of argon, krypton, and xenon are 2 to 3 times higher than that of the Sun. Such concentrations require very cold temperatures. This suggests that the material in Jupiter’s atmosphere must have originated at a much colder place than Jupiter occupies today. This challenges our current theory of planetary formation. 5. The colors seen in Jupiter’s upper atmosphere are likely due to chemical reactions induced by sunlight and/or lightning in its atmosphere. Another possibility is that impurities (such as sulfur or phosphorus) in the cloud droplets of water, ammonia, and ammonia sulfides result in the colors. Jupiter’s Interior 1. Jupiter’s gaseous atmosphere is a few thousand miles thick. 2. As one goes deeper in Jupiter’s atmosphere, gaseous hydrogen gradually becomes liquid hydrogen, but there is no distinct boundary. 3. At around 15,000 km below the clouds, it is theorized that the high pressure and temperature result in electrons moving easily from one atom to another, making the hydrogen a good electrical conductor; because it conducts electricity like a metal, we call it liquid metallic hydrogen. Most of the planet is made up of this state of matter. 4. Jupiter’s core, if it exists, is very small, contributing only 1% of the planet’s mass. 5. Jupiter’s magnetic field is quite strong— nearly 20,000 times stronger than Earth’s. Jupiter’s magnetic field is generated by its large mass of liquid metallic hydrogen and its rapid rotation rate. 6. Jupiter’s magnetic field deflects the solar wind around the planet as well as trapping charged particles of the wind in belts. 7. Jupiter’s magnetosphere—the volume of space in which the motion of charged particles is controlled by the magnetic field of the planet rather than by the solar wind— extends 15 million km from Jupiter and envelopes most of its satellites. 8. Jupiter’s field accelerates the charged particles in its magnetosphere to such high speeds that their temperature can reach 400 million K (25 times larger than that at the Sun’s core). However, the density of this plasma is very low for nuclear reactions to take place. The synchrotron radiation emitted by these particles is observed at radio wavelengths. 9. Powerful auroras form close to Jupiter’s poles, a thousand times more powerful than on Earth Energy from Jupiter 1. Jupiter emits more energy (about twice as much) than it receives from the Sun. This means it must have an energy source in addition to re-emitting the absorbed solar radiation. 2. There is no reason to support the idea that chemical reactions or radioactivity within Jupiter can be the source of this excess energy. 3. Jupiter would have to be 80 times more massive to support nuclear fusion; thus it cannot act like a miniature star. 4. Jupiter may still be shrinking and producing heat in the process but this is not enough to explain the observations. 5. It is now thought that Jupiter’s excess energy is left over from its formation; because of its great size, Jupiter is cooling very slowly. Jupiter’s Moons 1. Jupiter’s family of 64 moons can be divided into 3 groups: (a) 4 inner moons orbit very close to Jupiter and are probably fragmented moonlets. (b) 4 Galilean satellites, orbiting in nearly circular orbits (Io, Europa, Ganymede, Callisto); Europa, the smallest, is 7000 times more massive than the largest of the non-Galilean moons. (c) the majority of the remaining moons orbit in a different direction from the inner moons, have eccentric orbits, dark surfaces, and are probably captured asteroids. 2. Io, the Galilean moon closest to Jupiter, has active volcanoes. Voyager images suggested that Io’s lava flows were mostly molten sulfur but Galileo observed flows at 1800 K (much higher than sulfur’s vaporization temperature of 700 K). Thus, lava flows probably consist of rock formed by a large amount of melting of Io’s mantle. 3. Io’s energy is produced by tidal forces caused by its eccentric orbit around Jupiter. 4. Io is surrounded by a halo of sodium atoms. Other elements observed on Io: sulfur, oxygen, potassium, and chlorine. 5. Io’s density is about 3.5 g/cm3; this indicates that Io is composed mostly of rock. 6. Europa’s surface is ice; its moderate density indicates a rocky world covered by an ocean of frozen water. 7. Galileo data suggest that Europa has a magnetic field that reverses every 5.5 hours. It is possible that under the ice there is a layer of conductive liquid, such as liquid salt water. 8. There are few craters on Europa, suggesting that its surface is young and active so that craters do not remain visible for long. 9. Europa also experiences some tidal heating. 10. Ganymede—larger than Mercury —is the largest moon in the solar system. 11. Ganymede exhibits a less active, darker surface than Io or Europa. 12. Galileo data suggest that Ganymede has a small iron or iron/sulfur core, surrounded by a rocky mantle and a shell of ice at the surface. They also suggest that Ganymede generates its own field, most likely due to a thick layer of liquid, salty water under its crust. 13. Callisto, the outermost Galilean moon, shows more cratering, has the least active surface, and experiences little tidal heating. 14. Callisto seems to have a relatively uniform mixture of ice (40%) and rock (60%), with the percentage of rock increasing toward the center. 15. Callisto has the largest known impact crater—Valhalla— in the solar system. No signs of the impact exist in the region opposite to this crater, suggesting that a liquid layer exists under Callisto’s crust acting as a shock absorber. This idea is supported by Galileo magnetometer data. Summary: The Galilean Moons 1. The farther a Galilean moon is from Jupiter, the less active its surface, the lower its average density and the greater the proportion of water. 2. The Galilean moons formed slowly, over 100,000 to 1 million years, in a disk where the temperature remained low enough for ice to exist naturally. Jupiter’s Rings 1. Voyager I discovered thin rings around Jupiter. The rings are made of very tiny particles. 2. The rings are close to Jupiter, extending to only about 0.8 planetary radius from Jupiter’s surface. 3. The particles in the rings should not remain there for long, and they are thought to be replenished from the small moonlets within or near it. 9-2 Saturn Size, Mass, and Density 1. Except for its obvious rings, Saturn is similar to Jupiter. 2. Saturn’s density (0.7 that of water) is half that of Jupiter, due to a less dense core and a lower percentage of liquid metallic hydrogen. 3. The composition of Saturn’s atmosphere is similar to Jupiter’s: 96% hydrogen, 3% helium, 1% of heavier metals. Saturn’s Motions 1. Saturn orbits the Sun at an average distance of 9.6 AU; its distance from the Earth varies from 8.5 AU to 10.5 AU. 2. Saturn has an orbital period of 29.5 years. 3. Saturn is tilted 27° with respect to its orbital plane, so over time its rings appear in different orientations when viewed from Earth. 4. Like Jupiter, Saturn shows differential rotation. Its equatorial rotation rate is 10h40m. 5. Saturn is even more oblate than Jupiter, with its equatorial diameter 10% greater than its polar diameter. Pioneer, Voyager, and Cassini 1. We have learned much about Saturn from space probes (Pioneer 11, Voyager 1, Voyager 2, and Cassini) 2. Saturn’s magnetic field is only 5% as strong as Jupiter’s because Saturn’s liquid metallic hydrogen only extends about half way to its cloud tops. Saturn also has aurora around its poles. 3. Saturn’s clouds are less colorful than Jupiter’s because the colder temperatures at Saturn’s distance from the Sun inhibit chemical reactions that give Jupiter’s atmosphere its varied colors, and a layer of methane haze above the cloud tops on Saturn blurs out color differences. 4. Saturn has atmospheric features similar to Jupiter’s, but Saturn’s winds reach speeds 3 to 4 times faster. Saturn’s Excess Energy 1. Saturn radiates more energy than it absorbs. It also has less helium in its upper atmosphere than Jupiter has, by a factor of two (by mass). 2. The leading hypothesis in explaining both observations is that the cooling of Saturn’s atmosphere causes helium to condense to liquid form and rain downward. As the helium droplets fall, they lose gravitational energy, which is converted to thermal energy. Saturn’s Moons 1. Saturn has 47 moons, most of which consist of dirty ice. 2. Cassini observations suggest that most of Saturn’s inner moons have low densities, about that of water ice. The density, dark color, and retrograde orbit of Phoebe, an outer moon, suggest that it formed in the outer solar system and was captured by Saturn’s gravitational field 3. Enceladus is covered in water ice and its interior may be liquid today. Active geysers exists on this object; Cassini images show plumes of water vapor and ice water particles. What keeps Enceladus warm enough to maintain liquid water is still unknown. 4. The plumes provide a thin atmosphere for Enceladus that also includes carbon dioxide, methane, and other simple carbon-based molecules. Water expelled from Enceladus also forms a giant torus of vapor around Saturn 5. Titan is the second largest moon (after Ganymede) in the solar system with a diameter of 5,150 km. 6. Titan may be the most interesting moon in the solar system because it has an atmosphere, which is composed mostly of nitrogen with a few percent of methane and argon. There are also traces of water and organic compounds. 7. When sunlight breaks down methane in Titan’s upper atmosphere, organic molecules are formed; these molecules then slowly drift down to the surface. This raises the question of whether life might have formed on Titan’s surface. 8. Huygens data show bright highlands, deep channels, and dark lowlands that look like dried lake or river beds on Titan’s surface. Cassini radar imaging data suggest that large bodies of liquid (methane and ethane) exist over the high latitudes surrounding the moon’s poles. All the existing data suggests that Titan resembles Earth, with clouds, rain and seas. 9. Titan’s surface is shaped by winds, liquid flows, and tectonic activity. 10. Titan’s atmosphere is denser and 10 times more massive than Earth’s because its surface temperature of –180°C is low enough to keep gas molecules from escaping. Planetary Rings 1. Saturn’s rings are very thin, a few tens of meters across. 2. The rings are not solid sheets but are made up of small particles of water ice or rocky particles coated with ice. 3. Each ring particle revolves around Saturn according to Kepler’s laws. 4. Three distinct ring bands are visible from Earth, and named (outer to inner) A, B, C. 5. The largest division between the rings is known as Cassini’s division. This space is caused primarily by the gravity of Mimas and the synchronous relationship between the orbital periods of Mimas and of any particle in the Cassini division. 6. Other features of the rings are explained by the presence of small shepherd moons. The Origin of Rings 1. The origin of Saturn’s rings is not well understood but is thought to be the result of a close-orbiting, icy moon that was shattered by a collision with a passing asteroid. Another possibility is that an object from the outer solar system came too close to Saturn and was torn apart by the planet’s gravity. 2. Tidal forces are greater on a moon in orbit close to a planet than they are on a moon in an orbit farther out. 3. The Roche limit is the minimum radius at which a satellite (held together by gravitational forces) may orbit without being broken apart by tidal forces. 4. Saturn’s rings are inside Saturn’s Roche limit, so no moons can form from the particles in the rings. 5. If all ring particles were to be collected to form a small moon, its mass would be about 1/20,000 the mass of our Moon. 9-3 Uranus 1. Uranus, though barely visible to the naked eye, was unknown to the ancients. It was plotted on star charts as early as 1690, but Uranus’ slow orbital motion caused it to go unnoticed until Herschel discovered it in 1781. 2. The first reliable determination of Uranus’ diameter was made in 1977 during an occultation of a star by the planet. An occultation is the passing of one astronomical object in front of another. 3. Uranus has a diameter of 51,000 km (32,000 mi), 4 times that of Earth. 4. Uranus has a density of 1.27 g/cm3; it might have a very small rocky core or no core at all. 5. Uranus’ atmosphere is similar to that of Jupiter and Saturn: mostly hydrogen and helium with some methane. 6. Uranus does not have cloud layers, so the methane in its atmosphere, which absorbs red light, makes the planet appear blue. 7. Occultation data from 1977 showed that Uranus has a system of thin rings that contain very little material. 8. Uranus’ rings only reflect 5% of the sunlight that hits them so they cannot be seen from Earth. (Saturn’s rings reflect 80% of incident sunlight.) Uranus’ Orientation and Motion 1. Uranus’ equatorial plane is tilted 98° to its plane of revolution. This results in a retrograde rotation, as seen from far above the Sun’s north pole. It also implies extreme seasons since during each revolution, the planet’s north pole at one time points almost directly to the Sun and at another time faces nearly away from the Sun. 2. Uranus has an orbital period of 84 years. 3. Uranus has a fairly uniform temperature over its surface (about –200°C), indicating that the atmosphere is continually stirred up. 4. The axial tilt of Uranus was thought to be the result of a glancing impact with another object. Computer simulations, however, show that an axial tilt can arise naturally as a result of the strong gravitational interactions present during the early stages of the formation of our solar system. 5. Uranus has cloud bands that rotate differentially—16 hours at the equator and 28 hours at the poles. 6. Uranus’ atmosphere has about the same chemical makeup as Jupiter, about 83% hydrogen and the remainder helium. 7. Uranus’ magnetic field is comparable to Saturn’s. It probably originates in electric currents within the planet’s layer of water. The magnetic field’s axis is tilted 59° with respect to its rotation axis. No other planet has such a large angle between the two axes (though Neptune’s at 47° is close). 8. Five moons were known before Voyager; we now know of 27 moons. All are lowdensity, icy worlds. The innermost, Miranda, is perhaps the strangest looking object in the solar system. It appears as if it were torn apart by a great collision and then reassembled. 9. Two of Uranus’ moons are shepherd moons. Material in Uranus’ rings is very sparse; all of it together is less than the material in Cassini’s division! Historical Note: William Herschel 1. William Herschel, who has been called the greatest observational astronomer ever and the Father of Stellar Astronomy, was a musician. 2. He discovered Uranus using telescopes he built himself, which were of such quality that he was able to see things in the heavens that other astronomers couldn’t. 3. Together with his sister Caroline, they made the first thorough study of stars and nebulae, and discovered the existence of double stars. Advancing the Model: Shepherd Moons 1. Shepherd moons are a pair of moons, one orbiting just inside and another just outside the narrow ring, keeping the ring in a narrow band rather than spreading out over space. 2. The moon closer to the planet moves faster than the particles of the ring, and its gravitational pull increases the particles’ energy just a little, causing them to move outward in their orbit. 3. The moon farther from the planet moves slower than the particles of the ring, and its gravitational pull decreases the particles’ energy just a little, causing them to move inward in their orbit. 9-4 Neptune 1. Neptune is similar to Uranus, slightly smaller at 49,500 km in diameter. Neptune’s composition matches that of Uranus. Neptune’s color is also blue (because of methane in its upper atmosphere). 2. Unlike the nearly featureless Uranus, Neptune exhibits weather patterns in its atmosphere. It has parallel bands around it and its Great Dark Spot (photographed by Voyager 2) was similar in appearance to Jupiter’s Great Red Spot. 3. The wispy white clouds seen on Neptune are thought to be crystals of methane. 4. Neptune radiates more internal energy than Uranus, although the cause is unknown. This energy drives the weather on Neptune and results in winds that reach speeds of 700 miles/hr. 5. Neptune exhibits the most extreme differential rotation of any of the Jovian planets: 18 hours at the equator and 12 hours at the poles. However, these differences are confined to the upper few percent of the atmosphere. 6. Neptune’s magnetic field rotates with a period of 16h7m, which is taken as the planet’s basic rotation rate. 7. Neptune’s temperature is remarkably uniform at –218°C and its axis is tilted less than 30° to its orbit. 8. Neptune’s density is greater than Uranus’; this is probably due to a somewhat larger rocky core. Neptune’s Moons and Rings 1. Before Voyager Neptune was known to have 2 moons (Triton and Nereid); 13 moons are now known. 2. Triton, Neptune’s largest moon, is the only major moon to revolve around a planet in a clockwise (retrograde) direction. 3. Nereid has the most eccentric orbit of any moon in the solar system. 4. Triton has a light-colored surface composed of water ice with some nitrogen and methane frost. Its surface appears young, with active geysers and very few craters. 5. Triton’s density is about the same as Pluto’s. 6. The leading hypothesis in explaining the properties of both Triton and Nereid is that these moons were captured by Neptune after the initial formation of the solar system. Triton’s active volcanism is probably due to internal heating from tidal forces caused by Neptune’s gravity. 7. Stellar occultations observed in 1984 revealed that Neptune has rings. They are “lumpy,” perhaps as a result of undiscovered moons orbiting with them. Historical Note: Discovery of Neptune 1. As time went on after Uranus’ discovery, it became clear that it was not following the orbit predicted by Newton’s laws, even with the gravitational effects of Jupiter and Saturn taken into account. 2. Most astronomers thought that an unknown planet was disturbing Uranus’ orbit. John C. Adams, a 26-year-old British mathematician, took up the problem of calculating the position of the hypothesized planet. The French mathematician Urbain Le Verrier was making similar calculations of Uranus’ orbit. 3. Johann Galle in Berlin conducted a search for the unknown planet, and the new planet was discovered on the very first night of searching within 1° of Le Verrier’s prediction and 10° of Adams’. Advancing the Model Inside the Roche Limit? 1. The shepherd moons of Saturn’s F ring and those orbiting Uranus are within the Roche limit of each planet. They can exist there without being pulled apart. 2. It is an oversimplification to refer to a single Roche limit. For a smaller moon, the limit is closer to the planet than it is for a larger moon. 3. The position of the limit depends on the density of the moon. 4. The Roche limit concerns only moons that are held together by gravitational forces. A single large rock can exist inside the Roche limit, for it is held together by cohesive forces within the material. Chaotic Motions 1. In the mid-1990s, observations of the two of Saturn’s shepherd moons found them far from where they should have been based on Voyager data in the early 1980s. 2. Gravitational interactions between the moons and rings push them inward and outward repeatedly. 3. They are chaotic, meaning that their movements are not predictable because a very small difference in starting conditions can result in a big difference in later positions.