Symp_Intro_Prog_Parts_Abs

advertisement

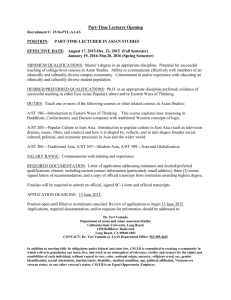

AHRC Diasporas, Migration and Identities Programme Workshops and Networks From Diaspora to Multi-Locality: Writing British-Asian Cities www.leeds.ac.uk/writingbritishasiancities Symposium Centenary Gallery, Parkinson Building, Woodhouse Lane, University of Leeds, LS2 9JT 17-18 March 2008 1 Contents: Thanks & Welcome p3 Network Outline p4 Symposium Programme p7 List of Participants p8 Paper Abstracts p9 Appendices: Appendix I: Report of the Bradford Meeting p18 Appendix II: Report of the Tower Hamlets Meeting p26 Appendix III: Report of the Manchester Meeting p31 Appendix IV: Report of the Leicester Meeting p36 Appendix V: Report of the Birmingham Meeting p42 2 Thanks & Welcome: Many thanks indeed for accepting our invitation to attend this symposium at the University of Leeds. The symposium is part of an AHRC Diasporas, Migration and Identities (DMI) programme network: From Diaspora to Multi-locality - Writing British Asian Cities. Funded April 2006 to September 2008, the network is co-ordinated by the four of us here at Leeds with the help of a steering committee comprising members inside and outside academia and from across the UK. The network aims to reflect upon the ways in which the ‘local’, ‘multi-local’ and ‘trans-local’ social, political, economic, cultural and religious dynamics of five distinctive ‘British-Asian’ cities (Birmingham, Bradford, Leicester, Manchester and London’s East End) have been ‘written’ at particular moments in time, from the 1960s to the 2000s. With an emphasis upon the existing and potential contributions of the Arts and Humanities and the Social Sciences, we are interested in a variety of genres of ‘writing’, representation and performance: ethnography; local and oral history; literary and cultural production; newspapers and the media; official reports. The network also considers the contributions of, and interactions between, differently located ‘insiders’ and ‘outsiders’, seeking especially to interact with, and be challenged by, those active and / or working in civil society and the ‘cultural’ and ‘community’ sectors. Thus far the planning and holding of events in each of the five cities has taken up most of our time. In appendices to this booklet you will find records of these meetings, the first of which was held in Bradford during June 2006 and the last in Birmingham just last month. The meeting records are also available via a developing website - www.leeds.ac.uk/writingbritishasiancities/. Here you can read existing work, register your own research interests and follow links to sites of interest. Against this background, the aim of the symposium is to provide the network organisers and steering committee with an opportunity to make presentations both to each other and to a select audience on the five cities and some key perspectives and themes. In many ways the symposium marks the beginning of the last leg of the network, a time when we shall principally be concerned with thinking and writing as a collective with a view to publishing an edited volume. Numbers at the symposium have therefore been kept deliberately small so as to facilitate an informal and productive interchange of ideas, something that has also characterised our city events. In the pages of this booklet you will find some more background on the network taken from our original application to the AHRC. You will also find details of the final symposium programme, a list of all participants and abstracts of the various presentations. Finally, as you know, all expenses in Leeds have been covered by the AHRC. For this we are very grateful. We are especially pleased to welcome the DMI programme director, Professor Kim Knott, as well as other DMI grant holders working on aspects of British-Asian diasporas, migration and identities. The Leeds Humanities Research Institute also deserves our thanks, both for the reception it is sponsoring at the end of our first day and its support for networking around South Asian Studies at Leeds, which first facilitated the four of us coming together. Drs Seán McLoughlin, William Gould, Ananya Kabir & Emma Tomalin 3 Outline of the Network: Summary: The diverse local character and trajectories of the South Asian diaspora in Britain today is the product of post-war immigration from particular parts of India, modern Pakistan and Bangladesh, as well as East Africa. Recognising that there is now an urgent need to reflect historically upon 60 years of this presence, the network will be the first to compare the changing dynamics of five British-Asian localities. It will examine how each presence has been ‘written’ by different constituencies in scholarly ethnography, novels and other forms of cultural production, as well as in the (local) media and official reports. Fit to Programme: This network revisits the study of South Asians in Britain. It interrogates the concept of ‘diaspora’ by probing the ways in which the ‘South Asian diaspora’ might be reconceptualised as comprising communities whose identity, on both individual and collective levels, is grounded in ‘multi-locality’. For the first time, the meaning and importance of ‘multi-locality’ will be explored through a comparison of five British-Asian cities, with ‘the local’ simultaneously speaking to precise regions people have migrated to and from. The ‘multi-local’ captures more effectively, we believe, the divergent experiences, cultural capital and mobilising energies of Asian groups in Britain—be they Bradford’s Mirpuris, Manchester and Birmingham’s Punjabis, Leicester’s Gujeratis and African Asians or Tower Hamlets’ Sylhetis. At the same time, we acknowledge the influence of still emergent, transnational forces, such as pan-Islamism, which are also deconstructing the idea of a ‘South Asian diaspora’ in Britain. In terms of complicating the dominant ‘race and ethnicity’ paradigm of the social sciences, firstly, there is a need and opportunity now to examine the multi-local dimensions of Asian-Britain historically. Almost sixty years after post-war immigration began, a sophisticated historical narrative about the changing dynamics of these communities is waiting to be written. Secondly, there is a pressing need for literary and cultural studies to scrutinise the cultural production of the grassroots as well as cosmopolitan intellectuals, exposing the fraught and nuanced processes of memorialisation, celebration, mourning and self-fashioning to fresh analysis. Thirdly, given the role of religious affiliations in reinforcing trans- and multi-local ‘ethnic’ communities, but also in the sustaining of more cosmopolitan and ‘universalising’ transnational circulations, the network will also prioritise new reflections on the explanatory power of religion. Finally, ‘multi-locality’ also signals the comparative nature of the proposed network. We ground an innovative understanding of Asians in Britain within regional micro-histories that in turn foreground the ways in which locality and community have been ‘written’, both by ‘outsiders’ and ‘insiders’, in terms of ethnography, literature, oral histories and official reports. Regional microhistories have also structured and shaped distinct modes of British-Asian cultural production – newspapers, novels, bhangra, film. By involving scholars working on any of these areas in specific cities of the UK, the network will question the very notion of ‘South Asians in Britain’ by uncovering the multi-local choices and forces shaping communities and their expressive practices. Providing opportunities for historical, comparative, practice-lead and innovative case studies, the network aims to extend in necessary and timely ways, the very understanding of the terms ‘diaspora’, ‘migration’ and ‘identity’. Rationale and Context: Alongside the maturation of British-Asian communities and their distinctive contours, there is the ever-increasing infiltration of mainstream popular culture by ‘Asian Cool’ in the form of fashion, food and fiction. Yet between that appropriation of easily assimilated cultural production and the 4 lived, variegated experiences of divergent South Asian communities in Britain, there are gaps and discrepancies which are symptomatically re-inscribed within policy-making, media reportage, and a general perception of the crisis of multiculturalism. The fragmentation and reformation of a composite ‘Asian’ identity since the rise of religious nationalism in South Asia and international politics post 9/11, have placed unprecedented pressure on diasporic communities. With this context comes new responsibilities on academia to shed light on the context of such pressures. Given the embeddedness of British-Asian communities within regional politics both in the UK and in South Asia, it is imperative that scholars enquire how far locality has (re)emerged as an axis of identity (re)formation. Through disciplinary and interdisciplinary reflection, a systematic comparison of multi-localities, and the careful involvement of ‘cultural’ and ‘community’ sector representatives, the network aims to generate fruitful and novel interaction, offering the results of our collaboration to policy-makers, arts and cultural initiatives, and a wide range of civil society actors. Aims and Objectives: Apart from the creation of a web resource on Asian Britain and other outcomes detailed below, the main aim of the network will be a forum for arts and humanities discussion of the South Asian presence in the UK. As an initial vehicle for this, we propose five meetings in Leeds, Manchester, Birmingham, Leicester and Tower Hamlets between June 2006 and February 2008. We also propose a symposium in March 2008 to consolidate and reflect upon the work on each locality. A steering committee will select invited speakers for each network meeting, briefing them to reflect upon the ways in which they themselves (or their organization / institution) have contributed to the ‘writing’ of the British-Asian city in question at particular moments in time. Looking to the future, the most important aim is to provide an environment of sustained and focused interchange for scholars based at different universities. Speakers and Participants: Speakers at network meetings would be drawn from academics (local and oral historians, ethnographers), representatives of the local media and local authorities, as well as representatives of British-Asian community organisations and writers (or film-makers, artists, musicians). Workshops in each locality will be open to wider members of the academic and other communities, although there will be a limit on total numbers of 30 to retain the intimacy of the network. Management: During the first two years the network will be coordinated from Leeds by the principal and coapplicants in collaboration with steering group partners from other universities and two nonacademics. The applicants have recently secured ‘pump-priming’ from Leeds Humanities Research Institute to co-ordinate South Asian Studies research in the Arts and Humanities across the university and a seminar series is up and running. The team has an excellent working relationship as well as individual experience of directing / consulting on research projects, organizing networks and conferences, and co-editing research outputs. The steering committee, chaired by the principal applicant, would meet in advance of, and immediately after, each network meeting. Its main business would be firstly to monitor planning and publicity, finalise invited speakers and other participants, approve web resources and manage the administrative support. Secondly, it would ensure the ongoing academic fit to programme priorities, reflecting self-consciously upon interdisciplinary themes and interpretations raised by each local meeting. 5 Outputs and Dissemination: a) A web resource for academic and non-academic audiences, containing: i) five openly edited papers on the ‘writing’ of British-Asian Bradford, Manchester, Birmingham, Leicester and Tower Hamlets; ii) webspace for the collation of new and existing electronic historical, literary-cultural and religious resources relating to these British-Asian cities; iii) a virtual exhibition explicitly comparing each locality. b) A conference paper presenting the findings of our exchanges. c) A book edited by the applicants publishing the five synthesized accounts / analyses of Writing British Asian Cities, together with a substantial introduction and conclusion. d) A collectively authored refereed article for reflecting on our research methodology and main conclusions. e) Invitations to the local press to contribute to (and report on) each workshop. At the end of the project national media will also be briefed with a view to special coverage. f) A short, accessible, electronic version of the final report available via the web resource for interested individuals, community organizations and institutions including non-academic participants in the workshops. 6 Symposium Programme: Monday 17th March 2008 Tuesday 18th March 2008 11.00 – 11.30 am: Arrival and Coffee / Tea 9.00 – 9.30 am: Arrival and Coffee / Tea Session I: Introductions Session III: Disciplines, Perspectives, Themes 11.30 am – 11.45 pm: The Programme (Kim Knott, Diasporas Programme Director) 11.45 am – 12.30 pm: The Network (Seán McLoughlin, William Gould, Ananya Kabir & Emma Tomalin, Leeds) 12.30 – 1.30 pm: Lunch 9.30 – 10.00 pm: Migrants & Multiculturalism: Discourses of ‘Brit-Asian’ in the Social Sciences (Shailaja Fennell, Cambridge) 10.00 – 10.30 pm: History, memory & the postcolonial: decolonising British-Asian histories (William Gould, Leeds, & Irna Qureishi, Oral Historian) Session II: Writing Five British-Asian Cities 1.30 - 2.00 pm: Writing British-Asian Bradford (Seán McLoughlin, Leeds) 10.30 – 11.00 pm: General discussion lead by Avtar Brah, Birkbeck (unconfirmed) 11.00 – 11.30 am: Coffee / Tea 2.00 - 2.30 pm: British Bangladeshis in London’s ‘East End’ (John Eade, Roehampton / Surrey) 2.30 - 3.00 pm: Writing British-Asian (Greater) Manchester (Virinder Kalra, Manchester) 3.00 – 3.30 pm: General discussion lead by Bobby Sayyid, Leeds 11.30 – 12.00 am: The British-Asian City & Cultural Production (Ananya Kabir, Leeds, & Aki Nawaz, Nation Records) 12.00 – 12.30 pm: Writing Religion in BritishAsian Diasporas (John Zavos, Manchester, & Seán McLoughlin, Leeds) 3.30 - 4.00pm: Coffee / Tea 12.30 – 1.00 pm: General discussion lead by Pnina Webner, Keele 4.00 - 4.30 pm: From the Belgrave Road to the Golden Mile: Asians in Leicester (Pippa Virdee, De Montfort) 1.00 – 2.00 pm: Lunch Session IV: Open Session 4.30 - 5.00 pm: Writing British-Asian Birmingham: Towards a Spatial Historiography (Richard Gale, Birmingham) 5.00 – 5.30 pm: General discussion lead by discussant Rajinder Dudrah, Manchester 2.00 – 3.00pm: Opportunity to hear about other projects on British-Asian diasporas, migration & identities 3.00 – 4.00 pm: Final discussion lead by Ato Quayson, Toronto 5.30 – 6.30 pm: Reception hosted by the Leeds Humanities Research Institute 4.00 pm: Coffee / Tea and Departures 6.30 pm: Transfer to Ibis Hotel & dinner at Hansa’s Restaurant, 72/74 North Street. NB Slavoj Žižek will be talking about his book, Violence , at the University today 6-8pm 7 List of Participants: Seán McLoughlin, Religious Studies, University of Leeds William Gould, History, University of Leeds Ananya Kabir, Postcolonial Literature, University of Leeds Emma Tomalin, Religious Studies, University of Leeds Irna Qureshi, Oral Historian and Freelance Researcher Aki Nawaz, Fun^da^mental & Nation Records Jasjit Singh, Religious Studies, University of Leeds Kim Knott, AHRC DMI Director & Religious Studies, University of Leeds Ruth Pearson, AHRC DMI large grant & Politics & International Studies, University of Leeds Sundari Anitha, AHRC DMI large grant & Politics & International Studies, University of Leeds Ceri Peach, Geography, University of Oxford Bobby Sayyid, Sociology, University of Leeds John Eade, Sociology & Social Anthropology, Roehampton University, London John Zavos, South Asian Studies, University of Manchester Pippa Virdee, History, De Montfort University Leicester Shailaja Fennell, Development Studies, University of Cambridge Richard Gale, Sociology, University of Birmingham Ato Quayson, Postcolonial Literature, University of Toronto Clare Alexander, AHRC DMI large grant & Sociology, London School of Economics Shahzad Firoz, AHRC DMI large grant & Sociology, London School of Economics Rajinder Dudrah, Drama, Music & Screen Studies, University of Manchester Eleanor Nesbitt, Religions & Education, University of Warwick Pnina Werbner, Anthropology, Keele Avtar Brah, Sociology, Birkbeck College, University of London Tariq Mehmood, Writer& Film-maker; AHRC Moving Manchester, University of Lancaster Virinder Kalra, Sociology, University of Manchester Anandi Ramamurthy, Film & Media Studies, University of Central Lancashire Georgie Wemyss, Centre for Research on Nationalism, Ethnicity & Multiculturalism, Surrey University Rehana Ahmed, AHRC DMI large grant & Postcolonial Literature, Open University 8 Paper Abstracts: Session II: Writing Five British-Asian Cities Writing British-Asian Bradford Seán McLoughlin, Religious Studies, Leeds Whether for its mela, said to be ‘Europe’s biggest Asian event’, or for the burning of Salman Rushdie’s novel, The Satanic Verses (1988), the story of ‘Brad-istan’, as it is sometimes dubbed locally, has been consistently documented, perhaps more than any other centre of the South Asian diaspora world-wide. Over a period of forty or more years, the iconic status of Bradford has been very publicly inscribed: ‘a miniature Lahore’ (Bradford Telegraph and Argus, 9 July 1964); a ‘Black Coronation Street’ (Sunday Mirror, 4 June 1978); and ‘the Mecca of the North’ with Ayatollahs of its own (Ruthven, 1991: 82). My argument here is that, beyond the headlines, a body of writing about Bradford now exists that is worthy of a new sort of reflection. Considered individually, works some will have read many years ago and perhaps forgotten, provide only snapshots of a British-Asian city from particular perspectives at particular moments in time. However, considered together, such snapshots can also begin to map, in broad outline, the emergence and changing shape of ‘Brad-istan’. My intention is to present a historical retrospective of sorts, based upon a close reading of a small selection of the many writings about the city. I want to dwell on the detail of these accounts and allow them to speak more on their own terms, and of their own contexts, than would normally be the case. Moreover, as we shall see, as well as pioneering the study of ‘British-Asian’ cities in the diaspora per se, many of the authors that have written about Bradford have made definitive contributions to their own academic disciplines or genres of literature. I shall first be re-examining the pioneering work of two anthropologists, Badr Dahya (1974) and Verity Saifullah Khan (1977). Taken together, their writing represents some of the earliest accounts of the social, economic and political functions of Pakistani ‘ethnicity’ as migrants settled in Britain during the 1960s and early 1970s. My second snapshot revisits Tariq Mehmood’s political novel, Hand on the Sun (1983), which is a unique account of resistance to the realities of racism in the 1970s. Set against actual events in Bradford, it provides much of the context for the emergence of a militant and politically ‘black’ Asian Youth Movement in 1978. Snapshot three focuses on Bradford Council’s trailblazing, but ill-fated, experiment in multicultural policy-making during the early 1980s. My main interest here is the insightful assessment of these new policies advanced by travel writer, Dervla Murphy (1987). Finally, a monograph by Philip Lewis (1994 / 2002), interfaith adviser and scholar of Religious Studies, provides my fourth and final snapshot. Set against the impact of local-global events such as the Rushdie Affair, as well as recent ‘race riots’ and 9/11, more than a decade after its first publication Islamic Britain remains one of the pre-eminent studies of the contemporary valency of religious identity amongst South Asian Muslim diasporas. As my narrative unfolds, account by account, I further contextualise the particular significance of each of these snapshots, adding my own extended analysis of the sum of their parts by way of conclusion. However, one of my overall arguments, worth anticipating here, is that unless we have a better understanding of social and historical change in ‘British-Asian’ cities like Bradford, we can not properly evaluate the reality of their contemporary dilemmas. While Bradford has, for example, often been represented, and presented itself, as an icon of ‘the multicultural society’, former chief of the Commission for Racial Equality, Herman Ouseley, has identified the city as 9 representing, ‘a unique challenge to race relations’ (2001: 1). The publication of Community Pride Not Prejudice: Making Diversity Work in Bradford, is an overdue admission of the failure of ‘multicultural’ policies in the city. However, set against the political context of a revived government emphasis on ‘integration’ under the banner of ‘community cohesion’ and ‘citizenship’, one of my main concerns with Ouseley’s report is that, read alone, it is in danger of decontextualising the emergence of Bradford as a particular sort of post-colonial, trans-national, ‘British Asian’ city, that has been in the making for at least half a century now. Representing others through text & performance: British Bangladeshis in London’s ‘East End’ John Eade, Sociology & Social Anthropology, Roehampton / Surrey This chapter will explore the ways in which people seek to represent the British Bangladeshi ‘community’ through writing texts and acting out those texts through public performance. I will begin by placing the locality – the ‘East End’ – in the broader context of London as a global city and urban sociology. I will then outline the contradictory character of dominant discourses about the ‘East End’ as Other – a place where the west London middle class were careful to tread and wrote about through certain interconnected negative tropes (poverty, criminality, immigration etc) co-existing with positive tropes of strong community, family and kinship ties. While London’s vast suburban hinterland has been largely ignored in most textual representation – reflecting most observer’s view of suburbs generally as ‘boring’ (see Hanif Qureshi’s journey from Beckenham to Barons Court in The Buddha of Suburbia – and the ‘West End’ has been celebrated by the tourist industry, the ‘East End’ has been explored in much greater detail by an array of writers (novelists, playwriters, poets, academics, missionaries, social reformers, community representatives, politicians, organisations and urban planners). This wealth of textual representation would seem to exhaust the possibility of gaps and silences. However, many gaps and silences remain and this will be as much a focus in my analysis of a particular representational process as the utterances and performances. To demonstrate these general reflections I will reflect on the meeting which we held at the Kobi Nazrul Centre and the exchange between the baul singer, the Centre’s Director and the three journalists. The exchange involved a performance in front of ‘insiders’ (Bengalis) and ‘outsiders’ (the rest of us) where certain themes were established. The exchange between the singer and the director could be interpreted as engaging implicitly with the issue of authenticity and who had the right to represent the 'community'. It could also be seen as a performance shaped by the intersection of gender, generation and class as well as ethnicity. In a broader perspective we can place the exchange within two different performative traditions - the hybrid tradition of baul singing in the Bengal cultural region and a more recent hybridised mode of using Bengali music to speak about racism and anti-racism in Britain. The media representatives gave another performance which revolved around what they could and could not do in terms of journalistic writing and the community constraints on them. Through these different performances we also see the mutual engagement of performer and the audience in the event and how the performers adapt to the audience’s reactions across the insider/outsider boundary. Integral to the event was the ways in which people used language – English, standard Bengali and Sylheti – to communicate with each other and to signal the boundary between ‘us’ and ‘them’. Implicit too was the power of language and the status of English as the dominant mode of discourse during the meeting and within British society generally. However, what did not emerge from this encounter was the significance of Islam as another dominant discourse. This 10 absence was a product of my own selection of contributors – secular Bangladeshi Muslims – in the desire to set a boundary around what would be acted out at the meeting. A different group might well have voiced Islamist critiques of the baul tradition and secular anti-racist politics. This critique would have reflected what I and others have written about as the glocal process of Islamisation. So, having established the key themes though this vignette I will place the event in the wider context of the history of the East End and the development of the Bangladeshi community in the locality from the 1960s/1970s first generation to the anti-racist struggles of the late 1970s and the 1980s to the process of Islamisation from the late 1980s onwards, which have engaged the second and third generations. I will then pull the two sections together through an examination of particular texts by certain writers performing for different audiences, specifically academics, novelists and community activists. Through this analysis I will explore further the limits of representation, the tension between different claims to authenticity inherent within identity politics and the ways in which writing undermines claims to be a ‘real insider’ as places change within the cosmopolitan global city. Writing British-Asian (Greater) Manchester Virinder S. Kalra, Sociology, Manchester Normative accounts of Manchester write the city in two halves which represent a social, economic and to some extent cultural divide. The North, South split of the conurbation is demonstrated in multiple genres of writing: academic, literary and policy. South Manchester is produced through a dominant narrative of vibrancy, in the economic and cultural sphere, with Rusholme and the Curry Mile an iconic space in which the City Council can celebrate multiculturalism. It is this road where the entrepreneurs, that are so central to Pnina Werbner’s anthropological account of Manchester, ‘The Migration Process,’ also find their businesses’ homes. A further textual representation is offered through the novel, ‘Curry Mile’ written by parttime writer, full-time local authority worker, Zahid Hussain. ‘Curry Mile,’ was published by a South Manchester based Black and Asian writers publishers called Suitcase Press, in turn funded by the Arts Council. In the Northwest, cultural policy in this area has written extensively about Asian exclusion from the arts. Yet Wilmslow Road is also the site where a visual arts project, managed by the Asian Visual Arts company, Shisha and art a South Asian lesbian and gay group (Sphere) can `mix-it-up'. Indeed, it is the ways in which academic, policy and cultural texts entwine to create a normative account of the sheen and shine of multicultural Asian Britain that creates a blurring, at the level of production as well as creation, of the various genres of writing about Asian Manchester. Similar narrative harmonies are present in the writing of the Northern part of Greater Manchester, but here the story is somewhat different. Rather than the optimism of the multicultural city, with its entrepreneurs and hybrid cultures, there is a story dominated by accounts of urban and social decay, civil unrest and endemic racism. Oldham is only 8 miles from the City of Manchester and a seamless urban sprawl merges their geographies. Nonetheless, Oldham has primarily been written from a policy perspective in terms of local and central government reports on riots and social deprivation. Indeed, the Ritchie report that followed the 2001 civil disturbances and its follow up is replete with stories of decay and decline. Academic work on these areas, such as that by Kalra (2000), also paints a picture of industrial decline and subsequent under-employment. Recent government statements depict these areas as ripe for Islamic extremism, further serving to create narratives of marginalisation. The shine of Rusholme is lost in the grime of the post-industrial landscape of inner-city Oldham with its apparent lack of economic success and irresolvable communal strife. 11 These dominant modes of writing the North and South of Greater Manchester belie the continuities that emerge from a focus on other types of writing, particularly those in vernacular languages. Rochdale, another town of Greater Manchester, is also home to the writer of the first Urdu novel about the journey to England, Hamara Safar, by Hashmi. South Manchester may be home to the only British based Pakistani satellite channel, but its’ staff is drawn from the North. Oldham and Rochdale are part of the Urdu newspaper and literary circuit with each town producing its own media in the form of free newspapers. The Pakistani community centres in Manchester and Oldham both play host to Urdu poetry which also writes the city in vernacular context. Breaking the North, South divide of Manchester is clearly possible in the way in which Rusholme is a regional centre for festivals such as Eid. Local mainstream media regularly reports on Eid, sometimes in celebration at others in terms of nuisance to residents or police harassment. Perhaps more fundamentally, the diversity and fluidity of Manchester, ossified in textual representations, belies the easy labelling of a British Asian City or of any ethnically marked identity space. For example the publication in the 1980s of the Pakistani Workers Association, Pekaar, was produced in South Manchester but its political message and campaigning work stretched way beyond the bounds of the city. This local focus with broader concerns is something that was prevalent in the event that was organised by the Writing the British Asian City project in Indus 5 restaurant in South Manchester. The participants, rather than producing something distinctively local about Manchester as a cityscape, evoked cross-cultural, cosmopolitan concerns. The glocal nature of Manchester can be seen in the shift of Pnina Werbner’s work from a local account of Pakistani entrepreneurs in the book The Migration Process to an overt concern with transnational political mobilisations, ostensibly with the same group of people, in the book, Imagined Diasporas amongst Manchester Muslims. In this second text the Manchester locality is almost incidental to the concerns that are being expressed. From the academic commentators through to the poetic performances the city was a site from which to make more general comments about Asian Britain. The writers and commentators present were using the city as an exemplary from which to push out from its boundaries or representing Manchester as a transnational rather than local space. These forms of writing are perhaps more aptly seen as part of an emergent South Asian or Asian Muslim transnational cultural sphere, in which writing the local becomes a conscious act, rather than an intrinsic part of the textual production. From the Belgrave Road to the Golden Mile: the transformation of Asians in Leicester Pippa Virdee, History, De Montfort From a reputation for racism in the 1960s and 1970s Leicester became a model of successful multiculturalism in the late 1980s and 1990s, one which has attracted – and continues to attract national and international attention. Analysis of the so-called ‘Leicester model’ has focused primarily on the role of local political leadership, the relatively prosperous and diverse nature of the local economy and the entrepreneurial skills of certain migrant groups (Singh 2003). Valerie Marett (1989) offers an historical study of Leicester in the ‘crisis’ period of East African Asian migration in the 1960s and early 1970s. Though the community was discouraged from entering Leicester the East African Asians still chose to settle down in the city and consequently played a pivotal role in the transformation of Leicester during the 1970s and 1980s. In the grand narrative Leicester is a city of East African Asians, home to one of the largest Gujarati communities in the UK, and a model of successful multiculturalism. Beyond this narrative Leicester is a city which is segregated, communalised and shortly to become the first minority white city. How do these identities, sometimes conflicting, feature in the writings of 12 Leicester? Surprisingly there is little written on Leicester outside the genre of racial and political history. Yet the city has a strong cultural identity and is one of the most vibrant. The Belgrave Road serves as a metaphor in the history of Leicester; from derelict and abandoned to economic prosperity and from all-embracing to exclusive. Writing British Asian Birmingham – Towards a Spatial Historiography Richard Gale, Sociology, Birmingham A regional, ‘second city’ with global aspirations, a service-sector economy of which the heritagetrail is founded upon pride in an industrial past, an increasingly buoyant node in an emerging network economy of which 40 percent of the metropolitan area is within the top 10 percent most deprived areas on a national scale: Birmingham is a city which is all too easily characterised in terms of paradox and contradiction. Such contradictions also find expression in the widely discrepant accounts of the British Asian presence in the city: for instance, the narration of Birmingham as a conduit for ethnic entrepreneurial success jostles uneasily with its portrayal as a racialised city in which examples of ‘success’ arise against a backdrop of structured exclusion from the formal labour market (Henry et al 2001; Ram et al, 2002, 2007). As this chapter seeks to show, however, at least some of the paradoxes that characterise the city generally and its British Asian communities specifically are a function of the differences of perspective of different authors, corresponding in turn to the varied paradigms and narrative traditions within which these authors write. Emblematic of this is that Birmingham has been home to two distinct and not infrequently opposed academic ‘schools’, the Cultural Studies approach of Birmingham University’s erstwhile Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies (CCCS), and the Weberian urban sociology of John Rex and his collaborators, both of them profoundly influential in shaping the trajectory of research around ‘race’ and ethnicity in Birmingham, Britain and beyond. Drawing on recent developments in critical urban studies, and in particular, the work of Henri Lefebvre (1991), Dolores Hayden (1995) and Leonie Sandercock (1998a, 1998b, 2003), this chapter develops a spatial historiography of writing on ‘British Asian Birmingham’, interrogating the varied ways in which constructs of space and South Asian ethnicity have been articulated together in different genres of urban writing – geographical, sociological, ethnographic and creative. The premise of the present chapter is that, whilst each of these genres of writing is inevitably partial, a critical juxtaposition of the different notions of ‘urban space’ upon which such writings rest, enables a much fuller account to emerge of the complexity and ‘dynamic tension’ that characterise at root South Asian experiences in and of Birmingham in the post-war period. Following a short introductory section on the history of South Asian settlement and community construction in Birmingham, the chapter is divided into three principal sections, each examining the notions of space – latent and manifest – that are brought to bear in different genres of literature. Part one examines the writing of urban geographers (Jones, 1970, 1976; Woods, 1979), revealing how cartographic representations of Birmingham’s ‘minorities’ have served to codify the locales of South Asian settlement in the city predominantly in terms of areal measurement and ‘segregation’. In the first section, I examine the urban sociological contribution, and in particular the seminal work of John Rex, as reflected in a series of major studies of ‘race relations’ in Birmingham written between the 1960s and 1980s (Rex and Moore, 1967; Rex, 1976; Rex and Tomlinson, 1979; Ratcliffe, 1981; Rex, 1988). Here, I consider the usefulness – as well as the excesses – of sociological theory building around ethnicity, class and urban systems. In particular, I examine how attempts to recast the Chicago School ‘concentric zone’ model of the city within a Weberian class perspective enabled issues of ‘race’, economic stratification and urban location to be addressed relationally, but in ways that arguably invested too much importance in the ‘status defining’ role of the housing market. 13 In the following section, I trace this critique out further through an engagement with ethnographic writing on South Asians in Birmingham, focusing particularly on the work of Dahya (1974) and Desai (1963), as well as the responses of the CCCS collective to Rex’s work (Hall, 1980; CCCS, 1982; Solomos and Back, 1995). In the following section, I move on to consider work straddling the period between the late 1970s and early 1990s, during which Birmingham’s economy underwent major economic restructuring, exploring the ways in which different authors have laid differential stresses on the constraining and enabling potential of the ‘new’ Birmingham economy for South Asian and other minority groups. Here, I also address the emerging literature on emerging ‘hybrid’ cultural forms in Birmingham, such as Dudrah’s recent work on bhangra (2002; 2007), and how these forms stand in a relation of ‘dynamic tension’ to other prominent strands of South Asian identity, such as the religious. In the final section of the chapter, I conclude by reviewing the scope for developing ‘alternative histories’ of South Asians in Birmingham, to encompass ‘moments’ that have so far been muted or eclipsed in existing accounts. Here, I consider how such alternative histories might be usefully facilitated by recent archival initiatives undertaken under the auspices of Birmingham City Council’s ‘Connecting Histories’ project, as exemplified in the collation and use of the Indian Workers Association archives (Dar, 2007). However, in a return to the core premise of the chapter, I make a case for the reflexive engagement with such archival materials, which are by definition not less selective or paradigmatically inscribed than materials used in extant accounts. Session III: Disciplines, Perspectives, Themes Migrants and Multiculturalism: Discourses of ‘Brit-Asian’ in the Social Sciences Shailaja Fennell, Development Studies, Cambridge The image of the South Asian migrant both reflects and reconfigures the changing face of the city in post-war Britain. The earlier political economy of labour market requirements of the 1960s has given way to debates around political allegiance and cultural differences in the 1990s. The movement from studying the ‘outsider’ migrant to engaging with notions of belonging provides a fertile area to understand how Brit-Asian has been constructed in social science analysis and to re-examine the conversations that abounded in that academic space. The shifting premises for migration are located in the global circuits of capital where the need for cheap labour which formed the backdrop to migration theory has been replaced by worries about control and containment of labour. Capitalist accumulation models have been replaced by cultural theories while the South Asian worker has transformed from the industrial worker to the taxi driver and from the newsagent to the restaurateur. It is in this context of the replacement of economic imperatives by cultural frameworks that the discourse of race sees a replacement of the term migration by the diaspora and with it the attendant concerns with multiculturalism. Postcolonial geographies of space and gender have been made an important contribution to broadening social science analysis of the South Asian presence in Britain as have theories of gender and race that have provided us with the tool of cultural imaginaries to traverse the lives and livelihoods of Brit-Asians. The intention of the chapter is to address the shifts in the terrain within which social science discourses have taken place, particularly to interrogate the move from work to word. This chapter will examine theories of migration that emerged in the early models of international development within British academic discourses (starting with the classic work of Arthur Lewis 14 and the Manchester school). The chapter will then examine the language of migration and the migrant that emerged in official documents and the manner in which labour markets were regarded by local council officials and other ‘outsiders’. The implications of the industrial workplace for communities of South Asians and how they constructed their own identity provide the first set of ‘insider’ readings that are available in the UK, from oral history archives and early labour union records. The chapter will then move on to analysing the shift from the migrant literature to that of multiculturalism, with a particular focus on how the move from work to word has impacted of the nature and space for ‘outsider’ and ‘insider’ commentaries. The chapter will conclude by returning to the world of social science theorising and draw out how shifts such as work to word, and migrant to multicultural have impacted on the academic sphere, and more generally on how the current intellectual concept of the cityscape/global city sits alongside the everyday lives and the emergent identities of being Brit-Asian. History, memory & the postcolonial: decolonising British Asian histories William Gould, History, Leeds & Irna Qureishi, Oral Historian This chapter will survey a collection of oral histories on the five cities on the one hand and broader survey histories in the academy on the other, looking primarily at the power dynamics inherent in the ‘doing’ of history. How have such histories ignored the voice of the unofficial – the common man, women or the family? The notion of silenced histories of British Asians also encompasses literary forms and genres, and the problems of English as the dominant medium of expression and presentation. The British Asian presence since the end of empire in the subcontinent has not been well documented by academic history, shy as it is to accommodate local oral histories, or historical memory. As a result, the oral history tradition around British Asians has tended to be dominated by popular histories or ‘surveys’ on the one hand (for example, Visram, Ansari), and by social science disciplines, which provide a kind of structural historical background to their field research on the other. The disciplines of oral history have been a stronger part, importantly, of the writing of academic histories in non-European contexts, and particularly where oral traditions have been so important to how history has been imagined. Much of this work has offered a challenge to the European Enlightenment traditions of positivism and textual representation – seeing them as an intrinsic mechanism of colonial power and expansion. An element of ‘othering’ (Abu-Lughod) takes place when one (colonized) world is represented for another (colonizer). British museum collections (British Museum, V&A) have also preserved and represented the authoritarian voice of Indian history. Tipu Sultan’s tiger, Maharaja Ranjit Singh’s golden throne, and Emperor Shah Jehan’s wine cup are among the V&A’s most prized Indian artefacts. Does this explain why the lacuna of the British Asian voice (particularly early migration experience) has been filled by oral history accounts generated from within the community? Oral history sources however help us to understand the ‘incredible variance’ in how these facts are perceived by different witnesses, languages and cultures (Young). The chapter will go on to explore how and why British Asians have been marginalised to the periphery of mainstream British histories. As a result, their narratives are ambiguously positioned in relation to the British state and establishment, reflecting ambivalent ‘British’ identities. Has this process produced parallel ‘subaltern histories’ in Britain too? Our treatment of the core cities (covered by the framework of the project) epitomise a kind of meta-history of Britain’s cities – covering issues which rarely feature in mainstream accounts and local histories, which tend to push the historical narratives of British Asians into the realm of public policy. The marginalisation of British Asians to the fringe of British history is also gendered. Texts on British Asian migration histories usually leave out the experience of women. They usually also omit histories of emotion and feeling and history of the family. Most accounts present a male 15 perspective, particularly with stories of pioneers (seamen, soldiers, mill workers). In turn, this is reflected back again in public policy, through race relations policies or the official celebration of ‘difference’ and multiculturalism. What does this tell us about the politics of ‘writing’ history around the ‘British Asian’ presence? To what extent are the historical silences linked to the British concentration upon and celebration of, a lost imperial past – something tied up with a concentration on the key moment in the process of decolonisation (see for example, Paul Gilroy) and the skewing of a British historical consciousness towards the ‘greatness’ rather than the injustices of imperial power. There has been however, a recent resurgence in the interest, for example in the links between British Asians, and events on the colonial past – the celebration for example of Indian independence and the discussion of partition. This was much more marked in 2007 than in 1997 - something which indicates a shift in the relationship between Europe and the Indian subcontinent. Recent debates in ethnography have helped oral history to flourish (first person narratives, life stories, or the idea of the creative historian or fieldworking historian). Ethnographers are now more acutely aware now of what difference who they are makes to what they see and experience, for example, the pros and cons of being a halfie (Abu Lughod), suggesting a notable power shift in ‘speaking from’ rather than ‘speaking for’. Has this contributed to the recent growth of British Asian writing, and what implications does this have for the emergence of more nuanced ‘British Asian’ historical narratives? The British Asian City and Cultural Production: Ananya Jahanara Kabir, English, Leeds and Aki Nawaz, Nation Records This chapter will examine the importance of cultural production within the British Asian communities/ cities that have been studied through the network. (nb: the phrase 'cultural production' is used to cover the range of self-expressive, self-consciously cultural practices that emerge from the communities under discussion. They can be proclaimed as straightforwardly 'insider' productions; alternatively, more complex relationships between author/ producer, audience and community may be triangulated. The work of analysis needs to attend to these complexities). It will focus on those cultural productions that have been on 'display' in the workshops organised by different steering committee members. In each workshop, certain 'products' were showcased by inviting appropriate community members/ practioners/ cultural producers. These productions were both witnessed by the workshop participants and made the subject of academic discussion. I am interested in analysing these double dynamics of the cultural product that is both performed and analysed, participated in and commented upon. The insider-outsider axis will thus be stretched to reflect on the workshop as a methodological space for the network. Issues of vernacularity and multiple voices, the body in performance, somatic memory and the relationship between the space of the workshop (always deliberately chosen as representative of the community under scrutiny) and the practice(s) and production(s) in question will be examined thereby. With food, music, sport, dance and performative poetry comprising, together with the more obviously visible 'novel in English', the full range of cultural productions displayed and discussed, the very notion of 'writing' the British Asian city will be interrogated and critiqued. Does 'writing', and its attendant politics of publishing and marketing, not close us off from the most vital and dynamic spaces of cultural production and contestation? The necessity of a nuanced literary critical mode of analysis, that is attentive to issues of genre, voice and symptoms of anxiety, self-assertion and pleasure within the text (broadly defined) will accordingly be foregrounded. Yet it will be argued that, for a project such as ours, this literary critical mode is most productive in conjunction with the other disciplinary perspectives the network brought together. 16 Writing Religion in British-Asian Diasporas Seán McLoughlin, Religious Studies, Leeds & John Zavos, South Asian Studies, Manchester In this paper, we explore the variety of approaches and themes which characterise how religion has been written in constructions of the South Asian presence in Britain. In postcolonial as in colonial contexts, religion has been projected by a variety of differently positioned agents insiders and outsiders, academics and non-academics - as a critical if not the defining element of South Asian identities at home and abroad. At the same time, historical and anthropological as well as religious studies approaches to the subject matter all emphasise the dynamic development and transformation of religious beliefs, practices, institutions and identities through time and across space, not least in contexts of migration, diaspora and trans-nationalism. Our intention here is to analyse something of these key processes of religious, social, cultural and historical change since the 1960s, as well as their representation in and through various forms of writing during the same period. In theoretical terms, during the 1970s and 1980s, accounts of migration from South Asia to Europe and North America were dominated by Sociologists, Anthropologists and others working largely within paradigms of race and ethnicity, with their respective emphases on the significance of social structure and cultural agency. During the last decade, however, accounts of diasporic South Asian popular and youth cultures inspired largely by Cultural Studies’ accounts have also emerged. However, none of these literatures provides a sufficient basis for thinking about the category of religion in its multi-local diasporas, not least in terms of the overwhelming persistence and continuing world-wide significance of ‘tradition’ in the face of cultural ‘translation’. Against this context, we reflect firstly on those in Religious Studies who pioneered the empirical study of religion and migration from South Asian to the UK from the 1980s onwards, paying special attention to the Community Religions Project at the University of Leeds (Knott 1986; Barton, 1986; Bowen, 1988; Kalsi, 1992; Lewis 1994). At the same time we argue that important recent theoretical developments in Religious Studies (Asad, 1993; McCutcheon, 1997; Flood, 1999; Fitzgerald, 2001) are beginning to impact the empirical study of religion in the South Asian diaspora. Taking this agenda forward, we explore the work of a number of scholars – mainly anthropologists and scholars of religion (for example, Baumann, 1999; Nye 2000; Leslie, 2003; Nesbitt, 2004; Knott, 2005; Mandair, 2006) - who have sought to locate empirical accounts of the diasporic reconstruction and public recognition of religion in terms of a broader set of questions concerning cultural reproduction and power – debates which have dominated the social sciences and humanities in recent decades. Only against such an exploration will it be possible to explore the problems and potentials of religion as a field for the elaboration of diasporic consciousness in the context of its growing significance as an identity marker in South Asian multi- and trans-localities. Moving between vignettes from the five city events and the dominant and demotic ‘texts’ that ‘write’, construct or perform the category of religion, we explore what we see as four key processes: i) migration, settlement and reconstruction / institutionalisation in urban environments; ii) public recognition by the local state; iii) multi-local and trans-local political networks, movements and imaginaries; iv) the more demotic and resistive interstices of syncretic traditions including the persistence of folk religious formations. 17