THE ACCESSIBILIY OF POSTSECONDARY EDUCATION TO

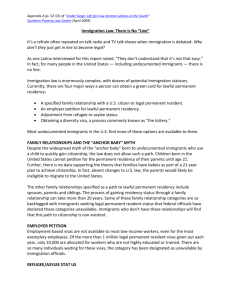

advertisement