Deontology, Individualism, and Uncertainty: A Reply to Jackson and

advertisement

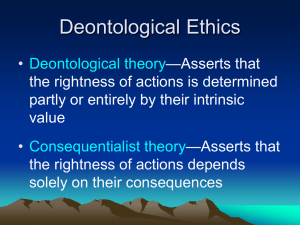

Deontology, Individualism, and Uncertainty: A Reply to Jackson and Smith Ron Aboodi, Adi Borer, and David Enoch 1. The Problem, and Two Examples Discussions of deontological moral theories typically focus on the advantages and disadvantages of deontological constraints, rules to the effect that some actions should not be performed – at least sometimes – even when performing them will maximize the good. And, of course, the jury is still out on whether deontological constraints can be defended. But in their recent paper "Absolutist Moral Theories and Uncertainty", Frank Jackson and Michael Smith1 emphasize not the general and well-known challenges to deontological constraints, but a more particular difficulty relating to what deontologists2 should say about cases of uncertainty. In their key example, a skier is about to cause the death of ten people by causing an avalanche. Jackson and Smith assume that whether or not it is morally permissible (and presumably also – given the possibility of saving the ten – morally required) to kill the skier (this is the only way of saving the ten) depends, according to a typical deontological theory, on whether or not he intends to kill the ten: If so, then he can permissibly be killed in self- (or other) defense. If not, then it is presumably impermissible to kill him, for presumably a 1 Frank Jackson and Michael Smith, "Absolutist Moral Theories and Uncertainty", Journal of Philosophy 103 (2006), 267-283; all page references in the text are to this paper. 2 Jackson and Smith put their challenge as a challenge not to deontology in general, but rather to absolutism (plausibly considered a particular instance of deontology). We explain why reading their challenge as a challenge to deontology in general is more interesting below, in footnote 5. deontological constraint forbids the killing of an innocent person, even in order to save ten innocent people from dying in an avalanche3. The problem, though, is that you don't know for sure whether or not the skier intends to kill the ten. In other words, the probability – p – of him being innocent (that is, of him not intending to kill the ten) is lower than 1, but higher than 0. The typical deontological view Jackson and Smith argue against forbids killing the skier to save the ten if p=1, and permits (and perhaps also requires) to kill the skier if p=0. But what does such a theory have to say about other values of p? The view according to which the constraint applies in all its force for any p>0 is highly implausible, for this view entails – in practical circumstances, where certainty is almost never present – the most extreme form of pacifism. The view according to which the constraint doesn't apply unless p=1 is a highly implausible understanding of deontology, for this view is – in practical circumstances, where certainty is almost never preset – extensionally equivalent with typical forms of consequentialism (without certainty, the constraint will just never apply). What else, then, can the deontological view say about cases with intermediate p? This is, of course, already a theoretically important question. But given that in the real world we hardly ever have certainty in such matters, this is also a practical problem. A deontological theory that has nothing to say about cases with 1>p>0 really has nothing to say about practically all real-life cases. The severity of the problem thus cannot be overstated. 3 We are not going to quibble over the details here: In the context of the theory of self-defense, it is highly controversial whether innocent aggressors can be justifiably killed. But nothing in Jackson and Smith's argument – or in our reply to it – depends on the details of the example of the target deontological theory. If you're not yet convinced, think about another example, one that is – unlike Jackson and Smith's skier example – entirely practical, and to which we will return below: The example of criminal punishment. Retributivists about criminal punishment – typically if not always deontologists – believe that there is a deontological constraint against punishing (or "punishing") the innocent, and so that at least sometimes it is wrong to "punish" an innocent person even when doing so promotes the good. But what do such theories have to say about the required burden of proof in criminal trials? If we are to require a certainty burden of proof, we will have a highly implausible theory of criminal punishment, according to which punishment is – in practical circumstances, where certainty is almost never present – never justified. If we say the deontological constraint against "punishing" the innocent only applies where there is no chance at all of guilt, we effectively take all content out of this deontological constraint. So what should a retributivist say about the appropriate burden of proof in criminal trials?4 2. The Threshold View Jackson and Smith consider several possible deontological replies, and reject them all. We will not address all of them in this reply. Rather, we are going to limit ourselves to just what seems to us the initially most promising deontological attitude towards uncertainty, and Jackson and Smith's most interesting argument against it. 4 Here's one possible reply to this question: "Retributivism (although not necessarily retributivists) is mute on how high standards of proof ought to be; …" (Jeffrey Reiman and Ernest van der Haag, "On the Common Saying that It Is Better that Ten Guilty Persons Escape than that One Innocent Suffer: Pro and Con", in Crime, Culpability, and Remedy (Paul, Miller and Paul eds.) (Basil Blackwell, Oxford, 1990), 242-3. We do more to place this argument in the context of Jackson and Smith's paper in a footnote5. One of the possible solutions Jackson and Smith consider is the one they call "the threshold version of absolutism" (275)6. We take this to be the obvious thing for the deontologist to say: In the skier example, for instance, there is a certain threshold 5 Throughout, Jackson and Smith make the mistake of modeling deontology (or absolutism – we return to the distinction between the two shortly) in very consequentialist-friendly ways. For instance, they consider understanding deontology as (just about) a consequentialist theory that places infinite negative value on constraint-violations, or just very large finite value on such violations. But this will not do, of course, because deontologists don't have to play the consequentialist value-game at all; they are, after all, deontologists. Also, Jackson and Smith choose to argue just against absolutist moral theories – theories, that is, according to which there are some constraints it is never justified to violate. But this restriction reflects a surprising – and disappointing – choice, for hardly any (secular) contemporary deontologist is an absolutist. Contemporary deontologists are typically "moderate deontologists", deontologists who believe that deontological constraints come with thresholds, so that sometimes it is impermissible to violate a constraint in order to promote the good, but if enough good (or bad) is at stake, a constraint may justifiably be infringed. By restricting their target theories to just absolutist theories, Jackson and Smith lose just about all initially plausible targets. And indeed, some of Jackson and Smith's arguments do not work against moderate deontological views (in particular, their argument against the "Big Bad Number" view (273-5) essentially relies on the target view being absolutist and not moderately deontological). But some of what Jackson and Smith say can be abstracted from these worrying problems. The problem mentioned in the previous section is, of course, a serious cause of concern for any deontologist, and the problem they raise for the threshold view – the problem discussed throughout most of this reply – is also generalizable in this way. 6 It is perhaps worth saying that the thresholds relevant here are different from the ones mentioned in footnote 5: Here these are probability-thresholds; there, they are thresholds regarding how much good (or bad) can justify infringing a deontological constraint. value for p, such that when p (the probability that the skier does not intend the deaths of the ten) is over that threshold value the deontological constraint applies in all its force, whereas when the value of p is below that threshold, the constraint doesn't apply at all. Let's call this threshold value "moral certainty". Our deontologist says, then, that if we know to a moral certainty that the skier intends the deaths of the ten, it is morally permissible (and perhaps also required) to kill him in order to save them, but if our (justified) confidence in the skier's murderous intentions does not rise to the level of moral certainty, we ought not to kill him even to save the ten7. Applied to the example of criminal punishment: The analogous threshold version of retributivism holds that we are only allowed to punish someone if we are confident to the point of moral certainty that she is guilty. If our confidence level is lower than moral certainty, we shouldn't punish, even if "punishing" promotes the good. Perhaps the traditional burden of proof in criminal trials – beyond a reasonable doubt – is meant to capture something like this view. 3. 7 Jackson and Smith's Argument against the Threshold Version The term "moral certainty" has a substantive part to play neither in Jackson and Smith's official statement of the problem, nor in our suggested solution. All that matters is that there is some threshold as described in the text. We use the term "moral certainty" only to simplify the wording later on. But note that Jackson and Smith seem to be using it in a way that renders true the judgment that it is morally permissible to kill the skier whenever we lack moral certainty that he is innocent (that is, that he does not intend to kill the ten). We, on the other hand, use it to render true the inverse judgment: namely, that it is morally impermissible to kill the skier unless we know to a moral certainty that he intends to kill the ten. We think that our use of the term is more in line with commonsensical intuitions as well as deontological tradition. And seeing that nothing hinges on this point here – both Jackson and Smith's argument and our reply can be stated without using the term "moral certainty" at all – there can be no objection to this choice of words on our part. Enter Jackson and Smith again, this time with the two-skier example. Assume two symmetrical skiers, X and Y, each in a position identical to that of the skier in the one-skier example with which we started: each, that is, about to cause an avalanche that will kill ten (different) people. And assume that we know to a moral certainty that X intends the deaths of "his" ten, that we know to a moral certainty that Y intends the deaths of "his" ten, but – as is surely possible8 – that we do not know to a moral certainty that both intend the deaths of the relevant ten. It then follows from the threshold version just described that we should (or at least that it is permissible to) kill X, that we should (or at least that it is permissible to) kill Y, but that it is impermissible to kill X and Y – for we do not know to a moral certainty that both intend to kill the (respective) ten, so the deontological constraint against killing the innocent applies. So the threshold version violates, at the very least, Agglomeration – the requirement that if one ought to Φ and one ought to Ψ then one ought to (Φ-and-Ψ). And as if this is not bad enough, the threshold version may be committed here to a highly implausible moral dilemma: For there is no way in which a conscientious agent can both, say, shoot X, shoot Y, and avoid shooting-X-and-Y. So the threshold version has highly implausible implications, and should therefore be rejected. 4. 8 A Way Out Suppose that moral certainty lies at a probability of 95%. And assume that the probability of X being innocent (that is, not intending the death of the ten) is 4%, and that the probability of Y being innocent is 4%. The probability that at least one of them is innocent is then roughly 8% (1-(.96*.96). In such a case, we know to a moral certainty that X intends the death of the ten, we know to a moral certainty that so does Y, and we don't know to a moral certainty that both do. In order to explain our way out, it may be useful to start with a simple example. Assume, then, a deontological theory according to which all and only deontological constraints are grounded in rights of individuals. According to such a deontological theory, for instance, the deontological constraint against killing innocent people is grounded in the right innocent people have not to be killed. And in order to avoid the accusation of having nothing to say in the real world, where 1>p>0, assume a threshold version of such a deontological theory, so that we are not allowed to kill a person (even in order to maximize the good) if we don't know to a moral certainty that she is liable to lethal self-defense (because, for instance, impermissibly attacking others). How will such a deontological theory fare in the face of Jackson and Smith's two-skier example? Unproblematically, it seems to us. X has a right not to be killed when innocent, but we know to a moral certainty that he intends to kill the ten, and so it is permissible – indeed, given the other features of the example, probably morally required – to shoot X. Similarly for Y. How about shooting-X-and-Y? Well, X-and-Y – presumably the mereological sum of X and Y – is not a right-bearing creature (perhaps rights can be had by entities other than individual persons, like maybe a family, or a nation; but surely to attribute a right to a mereological sum of persons is a category mistake). So there is no deontological constraint that directly requires that we not shoot X-and-Y. So the question whether we know to a moral certainty that both intend the deaths of their respective ten is simply morally irrelevant. Of course, there is no harm in aggregating duties: If we ought to shoot X, and we ought to shoot Y, then we ought in this case to shoot X and Y; and if we want, we can put this point by saying that we ought to perform the complex action of shooting-X-and-Y. But this way of putting things should not stop us from seeing that this complex action is normatively epiphenomenal: Its normative status is completely determined by the normative status of the more simple actions of which it is composed. So according to the kind of theory sketched here, in the two-skier example we ought to shoot X, and we ought to shoot Y, and (in a normatively epiphenomenal sense) we ought to shoot X-and-Y, and this result is not problematic, even though we do not know to moral certainty that both X and Y are attempting murder. Or consider a sort-of-contractualist deontological moral theory, according to which an action is impermissible (under a deontological constraint) iff someone can reasonably object to its performance9. According to such a view, so long as we know to a moral certainty that X intends the deaths of the ten, X cannot reasonably object to us shooting him, and so we are allowed to shoot him. Similarly, of course, for Y. How about shooting X-and-Y? Well, we know that X can't reasonably object to us so acting, and the same goes for Y. Who else could object? If X-and-Y were a morally significant entity, perhaps X-and-Y could object. But, of course, X-and-Y is not a morally significant entity. So no one can reasonably object to the action of us shooting X-and-Y10. And again, this is simply because shooting X-and-Y is normatively epiphenomenal on the actions of shooting X and of shooting Y. What these examples show, we think, is that Jackson and Smith's argument can be rejected in the following way: The normative status of the complex action shooting-X-and-Y is completely determined by the normative status of the more basic 9 This is very loosely based on Scanlon's contractualism. See Scanlon, T. M., What We Owe to Each Other (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1998). 10 This point is an analogue of the much-discussed issue of aggregation in Scanlon's theory. In that theory one can only reasonably reject principles on individualist grounds. See, for instance, Sophia Reibetanz, "Contractualism and Aggregation", Ethics 108 (1998), 296-311; F. M. Kamm, "Aggregation and Two Moral Methods", Utilitas 17 (2005), 1-23. actions shooting-X and shooting-Y. Though we can talk about the complex action as well, it is normatively epiphenomenal, and so no deontological constraint applies to it, and so the question of uncertainty at this level doesn't even arise. When we shoot both, there is no particular person whom we kill while lacking moral certainty of his murderous intentions11. And this is sufficient to show that our action does not violate the relevant deontological constraint. Jackson and Smith consider and quickly reject something like this suggestion (278). They say that the threshold version cannot deal with the two-skier example by saying that only the status of each action counts, because then whether or not we are allowed to shoot X-and-Y will depend on whether we're using two bullets (one for X and one for Y, in which case each shooting is allowed, and so so is the complex action) or just one powerful bullet to kill both (in which case this is the basic action, and it is wrong, because it violates a deontological constraint). It is important to notice that this reply doesn't apply to the line of thought sketched earlier. We do not claim that what matters is the number of actions performed. We claim, rather, that what matters is the nature and grounds of the relevant deontological constraint. Under the assumption (of which more shortly) that the relevant deontological constraint has something to do with X's moral status, or with Y's moral status, and that the mereological sum X-and-Y has no similar moral status, our solution holds. So what 11 At one point Jackson and Smith put their target theory thus: R'': "it is absolutely forbidden to form the intention to kill someone you believe with degree of belief p* or above to be innocent." (280) But, contrary to their suggestion, and in line with the thought in the text, R'' is not exposed to the twoskier problem. If a potential shooter follows R'' in the two-skiers case, there is no particular someone whom she believes sufficiently confidently to be innocent. Of course, she is sufficiently confident that at least one of X-and-Y is innocent. But this is not in violation of R'', as X-and-Y is not a "someone". do we say about the one-powerful-bullet-for-both-skiers example? Jackson and Smith are right in insisting that there cannot be a morally significant difference between killing both X and Y with one bullet and killing both, each with his own bullet. And we already know that we are allowed to kill both with two bullets (because we are allowed to kill each, and because there is no entity X-and-Y which is a right-bearer, or can object to actions, or some such). So it is also morally permissible to kill both with one powerful bullet. This action is permissible, because it doesn't violate any deontological constraint: there is no one person whom we kill even though we lack moral certainty of his intending to kill others. The thing to say, then, about the two-skier example is that – at least for what are arguably the most plausible deontological theories (more on this restriction shortly) – what matters are actions towards X and towards Y. So long as there is no one person whom we kill when lacking moral certainty that they intend the deaths of the ten, the probability that at least one of the relevant group of persons is innocent is not relevant to the applicability of the relevant deontological constraint12. 12 Jackson and Smith (276-7, fn 10) draw an interesting analogy between their problem for deontology and one version of the lottery paradox: In this version, a threshold view of (perhaps justified) belief is seen not to be able to adequately deal with a case of a conjunction of many propositions, each above the threshold; the conjunction itself can still be below it. And then a threshold view of (justified) belief arguably leads to inconsistency. Interestingly, we do not think that an analogous reply to the one in the text works for the case of belief: For the reply in the text relies on the fact that not any conjunction of normatively significant factors or classifications is itself an independently normatively significant factor or classification (shooting-X is normatively significant; shooting-Y also is; shooting-X-and-Y is not, except insofar as some significance follows from the simple actions of which it is composed). But precisely this claim doesn't work for beliefs. The conjunction of any two propositions is itself a proposition, and one about which we can most sensibly ask whether we should believe it. 5. Intending and Foreseeing But how can this be so? Isn't it still true that on our suggested way out your action – say, shooting X and Y with one powerful bullet – will amount to an intentional killing of someone whose innocence is not ruled out to a moral certainty? And isn't this precisely what the deontological constraint was supposed to rule impermissible? To see this worry more clearly, think of criminal punishment again. Our suggested solution, when applied to the criminal punishment case, reads something like this: If we "punish" an innocent person (or one in whose guilt we lack moral certainty), this person is entitled to complain, to object to us doing so, her right has been violated. But if we make sure never to punish someone unless we know to a moral certainty that they are guilty, no one is entitled to complain on account of us not knowing to a moral certainty that all those we consider punishing are guilty. The moral permissibility of the general punitive policy is just the by-product of the moral permissibility of each of its (normatively significant) components. But this, of course, raises the following worry: Suppose that beyond-areasonable-doubt denotes moral certainty, the threshold distinguishing between where the deontological constraint applies in all its normative force and where it doesn't. Then the policy of punishing people when their guilt has been proved beyond a reasonable doubt is – according to our analysis here – morally permissible. But with sufficiently many criminal trials, this policy is virtually bound to lead to the "punishment" of innocents. Indeed, the only way to avoid such cases is, it seems, to avoid punishing altogether. But if we do punish – say, after proving guilt beyond a reasonable doubt – the situation is not merely the analogue of the two-skier example, where we lack moral certainty that they are both guilty. Rather, in the criminal punishment case we know – to a moral certainty, easily – that we will punish some innocent people. But then how can our suggested way out possibly work in the criminal punishment case? Surely, if we know that a criminal punishment policy will lead to the punishment of the innocent, and if there is a deontological constraint against punishing the innocent, we shouldn't endorse this policy? We suggest that the deontologist rely here on the distinction between intending and foreseeing (or on some closely related distinction). If we decide to punish someone we know to be innocent (or just don't know to a moral certainty that she is guilty), we intend her "punishment" (say, as a means for deterrence). And so we violate the relevant deontological constraint. But if we adopt a policy that – we know – will result in the punishment of innocents, their punishment is not intended but merely foreseen. To see how this helps, think of other deontological constraints. Deontologists who believe in a constraint against harming people typically do not believe in a constraint against acting in ways that foreseeably harm people. Of course, that an action foreseeably harms someone is a morally relevant feature of that action, but it doesn't render it a violation of a deontological constraint against harming people as usually understood. To be a violation, the action has to intentionally harm someone. Similarly, then, for the case of punishment. The fact that implementing just about any criminal punishment policy foreseeably leads to the punishing of innocents is morally relevant. But this alone doesn't suffice for a violation of the constraint against punishing the innocent. What would be necessary for this is a case of intentionally punishing an innocent person. But implementing a criminal punishment policy that is bound to lead to the punishment of some innocents does not amount to intentionally punishing an innocent person (certainly not so long as we require proof to a moral certainty – beyond a reasonable doubt – of guilt as a precondition for punishment)13. Getting back to the question at the beginning of this section, then: that you cannot rule out to a moral certainty that your action in the two-skier case (shooting both with one bullet) will amount to an intentional killing of an innocent person is something you foresee, not something you intend. The deontological constraint doesn't apply.14 13 For the suggestion that it's a crucial part of justifying punishment that the foreseen cases of punishing innocents are merely foreseen and not intended, see Alan Wertheimer, "Punishing the Innocent-Unintentionally," Inquiry 20 (1977): 45-65, at 53-4. 14 There is nothing unique here in treating intentions as themselves foreseen and not intended. Discussions of the paradox of deontology and related issues often invoke scenarios where you foresee that (intentional) violations of a deontological constraint will follow your refusing to violate it now. We cannot discuss here in full some possible complications. For instance, perhaps the deontologist can help herself to the distinction between an ex-ante and an ex-post perspective on things. In terms of an entitlement to complain, in the punishment example no one is entitled to complain ex-ante, though of course the innocent person who is wrongly punished (despite proof beyond reasonable doubt) is entitled to complain ex-post. Armed with this distinction, perhaps the deontologist no longer needs also the intending-foreseeing distinction to get the desired results here. Nevertheless, we use the intendingforeseeing distinction in the text, for the following reasons: First, though some other distinction may do the work here, it seems like there are going to be cases where nothing but the intending-foreseeing distinction will do. (Consider, for instance, the distinction between someone employing a criminal justice policy merely foreseeing the conviction of some innocents as a side-effect, with someone intending such wrong conviction as a means for making the system more efficient). Second, as we say in the text, the intending-foreseeing distinction (or some distinction very close to it) is one deontologists probably need anyway, regardless of the discussion of uncertainty. And third, we suspect that the ex-ante – ex-post distinction derives its normative weight – if it has such normative weight from something very much like the intending-foreseeing distinction. Of course, the moral significance of the intending-foreseeing distinction is neither uncontroversial nor unproblematic15. But there is good reason to believe that any deontological theory needs something like this distinction anyway, even regardless of its attitude towards uncertainty16. So by relying on this distinction here the deontologist doesn't lose any further points17. If, in other words, you don't believe the intending-foreseeing distinction can be defended conceptually and normatively, most likely you weren't a deontologist even before reading Jackson and Smith. 6. How General Is Our Way Out? So this is how we suggest to save the threshold version of the deontological theory from Jackson and Smith's argument: The things that really count are the violations of individual constraints, or the violations of individual rights; and while aggregative and future violations are foreseeable, they are not intended, and so do not already constitute a violation now18. But it is important to note that this way out does not apply to all deontological constraints, and so nor is it available to all deontological theories. The second part of 15 For discussion and references, see David Enoch, "Intending, Foreseeing and the State", Legal Theory 13 (2007), 69-99. 16 Ibid., appendix. 17 Jackson and Smith consider intentions in the context of an attempt to amend the target theory by saying that what is morally forbidden is not in the first place actions but rather intentions. They rightly reject such a way of attempting to deal with uncertainty. But their reasons for doing so do not apply to the way intentions are used in the text here (as a part of employing the intending-foreseeing distinction). 18 And notice that this line of defense applies to absolutist theories – those Jackson and Smith explicitly argue against – just as it does to more reasonable deontological theories. this way out – relying on the intending-foreseeing distinction, or on some distinction very close to it – does seem to be one all deontologists can help themselves to (again, not because such distinctions are unproblematic, but rather because deontologists need them anyway). But the first part of this defense is not as universally available. Let us elaborate. What our solution relies on is the assumption that the relevant deontological constraints are grounded in individualistic patient-based considerations. In other words, we assumed – as is most clear in the examples of deontological theories we used in section 4 – that the relevant deontological constraints are grounded in thoughts about what individual people are entitled not to have done to them. Without this assumption, we no longer have a way of establishing our main claim in reply to Jackson and Smith, namely that – in the two-skier example – what is of moral significance are only the actions against each skier, not the complex action against both. But not all deontological theories offer this kind of support for their deontological constraints. Think, for example, about a deontological theory according to which we ought not to lie (even to promote the good). And assume that the rationale offered for this constraint has nothing to do with the rights or interests of the one lied to, but rather with the wholeness of the soul of the potential liar. Now construct an analogue of the two-skier example: Say, I'm pretty sure of two statements X and Y that they are true; about each, I am confident to a moral certainty that they are true, but about their conjunction I am not. Am I allowed to make these statements? Here too, as in Jackson and Smith's original example, it seems like it is permissible to make statement X, it is permissible to make statement Y, but it is impermissible to make both. But now our line of defense no longer applies: If the rationale of the constraint against lying has nothing to do with the one lied to, then the statement X- and-Y is a perfectly legitimate candidate for moral relevance, and the moral theory has to give an independent answer as to the permissibility of stating it. Or consider a patient-based view that nevertheless allows for unproblematic aggregation. According to one example of such a view, if you impose a 0.5 risk on me of being (unjustifiably) killed, I have, as it were, half a reasonable objection at hand; and if there are two people in my situation, then together we have a full reasonable objection, and so the relevant action is wrong. According to such a view it's quite possible that X-and-Y have available to them together a reasonable objection that neither has on his own, and then it's no longer true that the moral status of shootingX-and-Y is normatively epiphenomenal, and then our way out fails, and this deontological theory is again vulnerable to Jackson and Smith's argument. So in order to take advantage of our reply to Jackson and Smith the deontological theory has to be not only patient-based, but also individualistic, that is, it must disallow the kind of aggregation above19. And notice that the kind of aggregation it must rule out is subtly different from the kind of aggregation more commonly discussed. The issue of aggregation is usually brought up when there is no uncertainty, but rather (certain) relatively small harms to a number of individuals, and the question is how to weigh 19 We want to – and think we can – remain silent on the following interesting question: Is what's important here the number of individuals whose rights (say) are violated, or the number of rights violated? Assume a constraint against lying. If what's important here is the number of people whose rights are violated, then if I contemplate telling two distinct lies – L1 and L2 – to the same person, the category L1-and-L2 is a relevant category (the person lied to can complain about each lie, but also about both). If what matters is the number of violations, then each of L1 and L2 is a violation, and L1and-L2 is epiphenomenal. Different deontological theories are going to answer this question differently, and their answer will determine whether they can be defended against Jackson and Smith's argument by employing the defense in the text. this against a (certain) significantly greater harm to one individual. In our case, though, the aggregation is of probabilities, or of expected harm20. So there is room in logical space for a view that rules out aggregation in the more common sense, but allows for the aggregation of probabilities in the specified way. Such a view too, however, cannot utilize our solution to the problem raised by Jackson and Smith (and is arguably implausible anyway21). Let us not overstate this point. For our solution to apply, it is not necessary to assume any specific deontological theory. What is required, though, is that the relevant deontological theory be one that grounds constraints in individual patients (for instance, in what rights people have, or in what they are – individually – entitled to object to, or something of this sort). So Jackson and Smith's argument retains its force against some possible deontological theories (at least, our argument in this paper doesn't show otherwise). But individualistic patient-based deontological theories are off the hook. And seeing that these are arguably the more plausible deontological theories anyway, this result is not without interest. Indeed, Jackson and Smith's argument can be seen – given our reply – as an argument for the claim that if you're going to be a thresholddeontologist, the deontological constraints you believe in had better be grounded in patient-based, individualistic considerations. 7. 20 Remaining Problems If all that matters is expected value (see some discussion in the final section, below), then the two kinds of aggregation are effectively one. 21 On such a view, for instance, and given plausible background assumptions, a deontological constraint against punishment would entail that no criminal punishment system (bound as it is to lead to the punishment of some innocents) is morally permissible. With regard to a wide range of deontological theories, then, a threshold version of the view can satisfactorily deal with Jackson and Smith's argument. But the problem raised in Jackson and Smith's paper can be seen as a particular instance of the following family of problems: How should moral theories – deontological or otherwise – deal with uncertainty? We hope to have more to say about this wider issue on other occasions. Here, though, we wish to conclude by hinting at some of these related problems. One rather predictable difficulty – one anticipated and set aside by Jackson and Smith (276) – is another problem for threshold views. It is the problem of finding a non-arbitrary way of placing the relevant threshold. But we are not convinced this is a genuine problem, and a special one in this context (rather than an instance of the most general problem of vagueness), and so let us not say anything more about it here. But consider another problem. Jackson and Smith's paper deals with uncertainty about the nature of one's action or its results. But what if our ignorance runs deeper than mere uncertainty? What should we say of cases in which one of the things we don't know is the very distribution of probabilities over the relevant possibilities?22 Perhaps we can often deal with uncertainty by estimating the expected value of possible actions. But what can we do when – because of such deeper ignorance – we cannot even estimate expected values?23 22 There are well-known reasons to think that not all cases of such deeper ignorance are somehow reducible to cases of usual probabilistic uncertainty. See, for instance, Donald A. Gillies, Philosophical Theories of Probability (Routledge: 2000) 37-49. 23 Notice that this is a problem for consequentialists as well as for deontologists. This is an important point, because the problem Jackson and Smith focus on is not, of course, a problem for And what should we say if the ignorance involved is not of the relevant (nonmoral) facts (like whether the skier intends to kill the ten) but rather of moral facts? Suppose I know that the skier is in fact an innocent aggressor. And suppose that – having read much of the literature on self-defense – I am just not sure whether killing an innocent aggressor is morally permissible. How should a moral theory deal with this kind of uncertainty? 24 On the one hand, both in this case and in the skier case I end up not knowing for sure whether or not I should kill the skier. On the other hand, there does seem to be a morally relevant difference between factual and moral ignorance or uncertainty. But what is it? Return now to non-sophisticated, probabilistically quantifiable uncertainty about non-moral facts. Is it really plausible to say that only expected value counts? In Trolley, you have to decide whether to divert a runaway trolley from a track on which it is about to kill five, to another on which it will kill one. In Trolley* the situation is similar, except the trolley, if not diverted, is expected with probability of 0.5 to kill ten (and with probability of 0.5 not to kill anyone). In Trolley**, the undiverted trolley will for sure kill 5, but if diverted it will kill 10 with probability of 0.1 (and will kill no one at all with probability of .9). In Trolley*** there are 5 on the original track, but on the other track there are 10, each with an independent probability of 0.1 consequentialism at all, and so one may get the impression that consequentialism faces no serious difficulties in dealing with uncertainty. The point in the text shows that this is not so. 24 For some discussion, see Ted Lockhart, Moral Uncertainty and Its Consequences (New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000); Jacob Ross, "Rejecting Ethical Deflationism", Ethics 116 (2006), 742-768. For a discussion of this point in the context of a discussion of moral responsibility and blameworthiness, see also Gideon Rosen, "Culpability and ignorance", Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society, 103 (2003), 61–84; Alexander A. Guerrero, "Don't Know, Don't Kill: Moral Ignorance, Culpability, and Caution", Philosophical Studies 136 (2007), 59-97. of dying if the trolley is diverted onto that track. If only expected value counts in cases of uncertainty, there is no morally relevant difference between Trolley, Trolley*, Trolley**, Trolley***, and numerous other probabilistic versions of Trolley. But is this a plausible claim? So it is not at all clear how moral theories – deontological and consequentialist alike – should take uncertainty into account. This topic deserves much more research than it has hitherto received. The fact that Jackson and Smith's argument against deontology can be dealt with does not take anything away from the importance of drawing the attention of moral philosophers to this interesting host of issues.