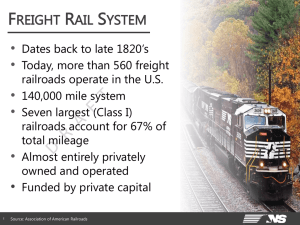

RAILROADS IN THE UNITED STATES

advertisement