Fat Embolism - developinganaesthesia

advertisement

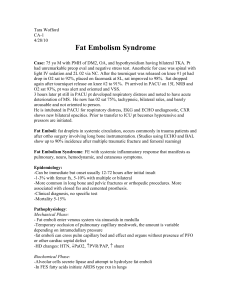

FAT EMBOLISM Introduction Fat embolism was first described in 1862 at autopsy by Zenker. In 1873, von Bergmann made the first clinical diagnosis of fat embolism. Fat embolism most commonly occurs in the setting of long bone (in particular femoral shaft) and pelvic fractures. The diagnosis is essentially a clinical one in the first instance and so the clinical setting will be the most important factor in making it. Clinically silent fat embolism is probably extremely common. Clinically significant fat embolism (“fat embolism syndrome”) whilst uncommon is an important condition to recognize, as it is associated with significant morbidity and mortality. Fat emboli are widely disseminated, but the lungs and CNS appear to be the most affected. Pathophysiology There are 2 current theories about the genesis of fat embolism: 1. Mechanical ● 2. Embolization of fat from medullary bone into venules. Biochemical ● Stress response with increased levels of catecholamines and corticosteriods leading to increased mobilization of fats that overwhelm normal transport mechanisms resulting in fat globules coalescing. The venous embolisation to the lungs may be explained by the mechanical theory whilst the biochemical theory may help explain CNS involvement. Microemboli may pass through the pulmonary into the systemic circulation. Causes Fat embolism syndrome is caused by: 1. Traumatic causes: ● 2. Long bone, (especially shaft of femur fractures) and pelvic fractures are by far the commonest causes. Non-traumatic causes: Rarely non-traumatic causes may be seen. Conditions that have been implicated in non-traumatic cases include: ● Diabetes ● Pancreatitis ● Burns ● Lipid infusions. ● Cardiopulmonary bypass. Complications 1. Respiratory ● 2. CNS ● 3. Hypoxia Depressed or altered conscious state. Release of free fatty acids from fat globules that result in toxic metabolites may result in: 1 ● Myocardial depression ● Vascular endothelial damage leading to hypotension ● An ARDS type syndrome. Clinical Features Classically the syndrome has been described as a triad of hypoxia, neurological disturbance and petechiae, however the syndrome can be more widespread than this and it should be remembered that fat globules are widely disseminated. Symptoms generally appear around 12-72 hours after injury. 1. CVS ● 2. 3. Persistent unexplained tachycardia will often be the first symptom. Respiratory ● Tachypnea and dyspnea will commonly occur early. ● Progressive hypoxia Neurological CNS disturbance disproportionate to any hypoxia is characteristic. 4. 5. ● Cerebral agitation and confusion are commonly seen. ● In more severe cases depression of conscious state may occur progressing to coma in some cases. Petechiae ● A petichial rash may develop later in the progression of the syndrome. This is thought to be due occlusion of dermal capillaries by fat globules and is unrelated to any platelet dysfunction. ● Typically the petichiae appear over the upper body, including the head, neck, chest, axillae, conjuntival and oral mucosa. ● Petichiae resolve spontaneously within 5-7 days. Progressive systemic involvement: ● In severe cases symptoms may progress to an ARDS type syndrome. ● Thrombocytopenia. ● Hyoptension. ● Anemia Investigations There are no specific diagnostic tests for fat embolism. Investigations therefore will largely be directly to ruling out other diagnoses and establishing how unwell a patient is. Blood tests ● FBE ● U&Es/ glucose ● CRP ● ABGs. CXR ● This will be normal in the majority of cases. ● There may be bilateral pulmonary alveolar infiltrates ECG ● The commonest finding will be sinus tachycardia Fat globules ● Contrary to some reports fat globules in urine, sputum or wedged PA catheter blood (detected by specific staining techniques) is not diagnostic. This is a common finding in trauma and so not helpful in making a diagnosis of fat embolism. CT scan CTPA ● This cannot make the diagnosis of fat embolism, but may need to be done when large pulmonary embolism needs to be excluded. CT scan brain ● This needs to be considered for any acutely confused patient to rule out alternative diagnoses for CNS symptoms. Management There is no specific treatment for fat embolism and so management is entirely supportive. 1. ABC issues ● The most important initial considerations will be management of the patient’s conscious state and oxygenation. ● 2. Early operative fracture fixation ● 3. Serious cases will require intubation and ventilation. Early operative fracture fixation reduces the incidence of fat embolism syndrome. Any patient suspected of having fat embolism syndrome should be referred to ICU. Prognosis ● Overall mortality ranges from 5 to 15%. 1 ● Multiple fractures are more likely to result in fat embolism syndrome. ● Mortality is increased in patients with significant co-morbidities. References 1. Up to date Website, September 2006 Dr J. Hayes August 2007