Cross Cultural Negotiation Handout

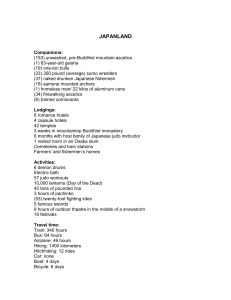

advertisement