Billy Bunter the Bold

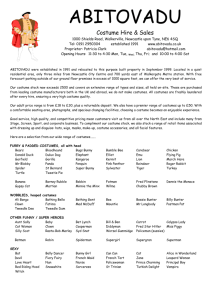

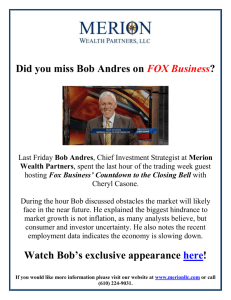

advertisement