Shrimp Hatchery & Nursery Operations in Bangladesh Report

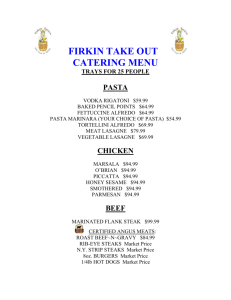

advertisement