Regional Workshop on Results Oriented M&E

advertisement

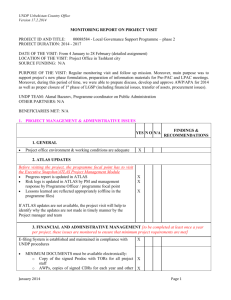

WORKSHOP REPORT (Final) Regional Workshop on Results Oriented M&E . Main Issues and Conclusions . . . . . . . . Cape Town, 28-29 November 2004 1 . The Evaluation Office organized a Regional Workshop on Results Oriented Monitoring & Evaluation for countries in the African region in Cape Town from 28 to 29 November 2004. This regional workshop forms an important part of the assessment of M&E practices and the build up towards a corporate policy on evaluation. Participants in the workshop included Deputy and Assistant Resident Representatives, Programme Advisers and M&E Focal Points from UNDP Country Offices as well as representatives from the Governments of Nigeria and Zimbabwe. The workshop had the following main objectives: 1. To mainstream results oriented M&E and to reinforce the links between M&E and development results. 2. To promote a dialogue on the evaluation function in UNDP and the UN system and to further refine evaluation methodologies. 3. To identify demands, practices and lessons learned on M&E for informing the formulation of corporate country policy on evaluation as well as a strategy on capacity building. 4. To interchange experience and practices on monitoring and evaluation among country offices, government and other stakeholders. In preparation for the formulation of a corporate country policy on evaluation, an assessment of M&E practices is in process, to ensure that the future policy is grounded in genuine practices and needs on the ground in country offices. Consultations are also being conducted at different levels. Some actions so far have included: o o o o o Outcome evaluation review November 2003 – March 2004 Sarajevo and Kuala Lumpur workshops February 2004 EvalNet survey July/August 2004, other EvalNet discussions Country evaluation workshop in New York November 2004 Internal assessment of country M&E practices in selected countries ongoing since September 2004 Some preliminary findings from this assessment were discussed at the Cape Town workshop. The attached concept note and agenda outlines the scope and background for the workshop in more detail. The following summary highlights key discussions, issues and conclusions from the proceedings of the workshop, while detailed presentations made and papers presented by participants are attached. 2 1. Opening Session Following opening and welcoming statements by Mr. Thulani Mabaso, on behalf of Mr. Isaac Chivore, OIC of UNDP South Africa, and Ms. Saraswathi Menon, EO Director, three rich presentations discussed the broader and increasingly complex backdrop and context for development at the national, regional and global level, and UNDP’s role in this picture. They further posed some challenges for the monitoring and evaluation function. Some of the key points are summarized below: The Deputy Chief of UNDP’s Regional Center in Johannesburg, Mr. Joseph Mugore’s presentation highlighted the following points with respect to Africa’s development context: High growth rates are observed but at the same time poverty is spreading and deepening. A number of externally defined national economic management schemes have been introduced over the years but national ownership has been questionable. To address this, there is, among other things, need for a strong state. The links between democracy, freedom and development need to be further explored and seen in relation to aid dependency. Involvement of civil society is important but NGOs are not always representative bodies. Genuine participation and ownership of the broader civil society and private sector would eliminate problems with capacity and absorption constraints. Consequently, with appropriate policies, delivery and implementation issues are less important. The MDGs are disputed goals, some say they would not be achievable in Africa, but in reality they would be achievable with an appropriate paradigm shift. Both resource gaps and capacity gaps exist but could be addressed with a paradigm shift. The President of IDEAS, Mr. Sulley Gariba’s keynote address raised the following points: UNDP has been key to introducing a people-centered approach to development. The MDGs have created an opportunity for a compact between developed and developing countries, and for an adequate distribution of roles. On monitoring and evaluation, there is a strong need to further involve citizens, civil society, legislative bodies and other that so far have not been sufficiently involved. There should be genuine interaction among various groups of stakeholders, ensuring that public policies and private sector relate to each other. A key question to ensure substantive accountability is who commissions evaluations. With changing participation in M&E, tools and capacity building approaches need to change as well. The scope of M&E needs to go beyond aid, and UNDP has already taken initiatives in this direction. Imbalances between national institutions and traditional, external development institutions need to be leveled out. 3 The Country Director for UNDP Sierra Leone, Ms. Nancy Asanga made the following comments as a discussant: Important changes are under way in Africa, including a higher level of demand for ownership. Participation and capacity development of local partners are important, for development processes as well as for M&E specifically. With Sierra Lone as an example, the integration of M&E into the inter-agency Consultative Group process has proven successful. The EO Director, Ms. Saraswathi Menon, outlined the perspectives from the Evaluation Office as follows: At present, there is no UN system wide function for evaluation. The emerging UNDAF evaluation mechanisms will be an important step in this direction. The United Nations Evaluation Group (UNEG) is also working on common norms and standards for the future. Evaluation in UNDP has achieved institutional ownership, but a requisite independence of the function has been retained at the substantive level. There has been an important modernization of evaluations, going to a more upstream, results based model, but there is still some way to go in terms of establishing a culture of assessment and fully engaging senior management, in order to ensure that M&E is utilized to its full potential in strategic management and decision making. One of the key issues in this regard will be to ensure that adequate capacity is in place at all levels. In moving towards an evaluation policy, three key questions need to be asked, for which input from the COs is welcomed: Further defining the purpose and role of evaluations, achieving balance between accountability, learning and management needs; establishing the right balance between compliance and optional approaches; and setting the appropriate objectives for evaluations, i.e. whether we are evaluating for processes or results. Key issues raised during the plenary session included: Broad overview of shifts in development and evaluation paradigms- from concern with inputs and activities to focus on results and development effectiveness Sea change in the South- greater demand for accountability and results by both government and civil society. Key challenges for M&E is how to promote and support development effectiveness, ownership and capacity development and meet the need for “professionalization” of the field and greater and more effective coordination and harmonization Tensions between aid effectiveness and development effectiveness High growth rates in Africa over the last few decades but this has not translated into higher human development indices. In some cases paradox of high growth rates and fiscal discipline alongside deepening poverty. Value of national planning –allows setting agendas in programme countries but SAPs and PRSPs have eroded and replaced this function and in most cases 4 weakened already weak states in setting the national development agenda Policy choices rather than growth or democracy on their own determine and/or influence poverty reduction. Emerging global and national consensus on what constitutes developmenthuman development, human security and lately MDGs. UNDP key contributor in shaping fundamental shifts in development thinking to human centered development and a more multidimensional notion of what constitutes development (human poverty , human security etc) Compact between developed and developing countries on the need to forge partnerships, policy coherence and promote country ownership. Fundamental questions for M&E are: What to evaluate, who commissions evaluations, who evaluates and how to evaluate ( methods and approaches) Bridge asymmetrical relationships and broaden constituencies beyond Ministries of Finance e.g. new independent public evaluation institute. Emerging trends point to the need for evaluations to target and mobilize citizen participation and parliaments which offer potential for strengthening accountability. Outcome based evaluations entail need for partnerships 2. Approaches to M&E at Country Level Two strong presentations of actual case studies were made by the Uganda and Tanzania country offices as follows (copies of presentations are attached): (i) Ms. Rose Ssabatindra, M&E Focal Point, UNDP Uganda; “Using M&E to assess progress towards the MDGs and PRS(P).” This presentation introduced the PEAP, Uganda’s version of the PRSP, and discussed the use of RBM approaches and strategic M&E in the public sector reform programme. UNDP plays an important role, among other things in leading one of the MDG working groups. (ii) Mr. Amon Manayema, Leader, Poverty Unit, UNDP Tanzania; “Monitoring and Evaluation of Poverty Reduction Strategies in Tanzania.” This presentation discussed the comprehensive system of working groups and surveys around Tanzania’s PRSP, and how this has strengthened the collaboration between Government and donors on strategic issues. Both presentations pointed to the opportunities and potential for greater national ownership , coordination and harmonization , reduced transaction costs as well as the development of mutually agreed ( governments, sub national entities , citizen groups, donors ) comprehensive national M&E frameworks and tracking systems with clear and specific target setting, bench marking and focus on development results. Both also pointed to the complexities and process heavy systems now in place to monitor PRSPs/PEAPs, the parallel reporting systems and noted how budget/resource needs , ( a short term horizon ) often detracts from the focus on development results and national ownership. 5 The discussion following the presentations addressed, inter alia, the potential for UNDP to build national capacities of government entities and citizen groups to build credible M&E systems that track higher end development results ( e g. MDGs ) ( In the absence of such an approach there may be risk of marginalization and/or lack of alignment with national M&E frameworks of government and donor partners.) 3. Group-work: Assessment of Current M&E Practices at the Country Offices Participants formed three working groups and each was asked to address one of three predesigned questions to assess the current M&E practices in the country offices and their linkages with those of other partners, including national governments and institutions. The following is a summary of key points presented by the groups to the plenary: Key Issues – Group 1 The group discussed the following topic: How do M&E instruments link up with overall government strategies? The topic was discussed at three levels and in three categories - the M&E instruments, problem/challenges and solutions that are summarized below. Some observations under the instrument category were: Some countries have an audit system at national and local levels Household Surveys and National Census exist Monitoring Institutions exist Regular Reviews and Reporting are undertaken UNDAF and MDGs are good instruments PRSPs / National Development Plans/ MTEF are available for M&E NDRs and MDG Reports are a source of evaluative evidence Public Hearings by Parliament and Parliamentary Committees could contribute to M&E Problems / Challenges: Different UNDP & Government Review and Reporting Cycles Different Government and donor agency mechanisms (who is driving ?) Poor capacity Poor harmonization within the UN system Not all national plans have and M&E component UNDP can only realistically and strategically link with certain government systems COs do not “reach out” sufficiently Who owns the process? Are we concertedly building ownership? 6 Authenticity of baseline data? – gap between the development status quo and the desired outcome Poor “inclusion” i.e. development effectiveness (poor ownership resulting in UNDP building M&E systems for itself). Solutions: Joint/Consensual UNDP/Government decision-making meetings ensuring government is driving the process Joint assessments at programme design stage and joint evaluations during and after implementation Use of ROAR as an instrument for programme management between UNDP and Government – increased collaboration through pro-active engagement based on empowering government leading to better harmonization Build credible self-assessment systems through harmonizing national and local indicators with MDGs Setting mutual agreed and realistic targets using proxy indicators aligned to MDGs Investing in capacity building to address specific M&E problems by agreeing on common problems, instruments and systems Outcome instruments to be brought “in line” with existing PRSP and budget support indicators Bring “visibility” of the M&E function closer to the Country Level. The discussion also focused on clarification of how the ROAR could be used as an instrument for harmonization. The group members explained that the ROAR is more of an instrument for management actions, not an M& E instrument per se. Key Issues – Group 2 The group discussed the following topic: In the broader context of the national development situation (e.g. MDGs, Governance Reform, HIV/AIDS, PRS(P), Direct Budget Support by bilateral and multilateral donors), how does UNDP’s result-based M&E practices reconcile the tension between institutional compliance and assessing development results? Key issues presented by the group were: RBM tools need to introduce accountability and oversight. The ATLAS Project, Country Programme outcomes, SRF, MYFF and Core Results should also introduce accountability oversight. Country Office Monitoring and Evaluation Team to be established under the leadership of a member of a senior management for Learning/Information sharing and enhancement of knowledge. The arrangement to result in effectively undertaking reporting, accountability, and oversight functions. 7 Country Office monitoring and evaluation processes and systems should link with government/NGOs/CBOs and other partners. The M&E regime does not dovetail well into the new corporate tools and processes being introduced. There is need for the Bureau and EO to work on this. There is need for the M&E function to be supported by the audit function. The presentation provided a base for intensive discussions and views on the structure of M&E in the office. Various models were presented including DRRs' functions having M&E office functions, Senior National Officer heading M&E functions in the office, integrating functions in staff job descriptions. The meeting left the arrangements to the individual country offices. Key Issues – Group 3 The group discussed the following topic: What are the most significant challenges for CO to mainstream results-oriented M&E? The following were identified as major challenges for country offices to mainstream results-oriented M&E: How to harmonize different systems and tools of various partners including the national governments Shift of monitoring and evaluation paradigm resulting in complexity of M&E concepts as it relates to looking at results and the need for a common understanding Internal and external capacity building Keeping all stakeholders/partners at the same level of understanding. Internal and external capacity building. Developing evaluation culture in CO. Time required for results to be evident. Developing M&E capacities of staff (day to day monitoring) M&E model – dedicated M&E person. Make sure M&E is demand – driven making budgeting for M&E mandatory. Resource mobilization for ECD. Elaborate mechanism for M&E follow-up. Ownership of the M&E process. Soft intervention M&E methodologies/indicators. Linking country offices based results into global M&E framework. 8 4. Wrap-Up of Day 1 Proceedings: Main Issues and Conclusions A presentation was made by Ms. Fadzai Gwaradzimba, Senior Evaluation Advisor, EO, summarizing the main issues and conclusions discussed during Day 1. The text of the presentation is attached. Some of the main points highlighted were: The presenters formulated key challenges for M&E and development work globally, regionally as well as at the country level. There is a “sea change” taking place in the South, in terms of ownership and policy development, and UNDP is challenged to keep up with this change. The weakening of the state is a key issue to be addressed. Important policy choices lie ahead, among other related to the relationship between democracy and development. Some gaps do exist in the current M&E tools and systems. Some key questions include: What capacity exists within our current network? How does UNDP support national processes and systems? There is a need to close the gaps between national and international agendas and capacities. 5. Networking for capacity building in M&E: The case of the Niger Network Presenter: Jean-Charles Rouge, M&E Specialist, UNDP Niger The session focused on how ReNSE has been contributing to sustainable evaluation development capacity (ECD) in Niger and the extent to which UNDP’s involvement in ReNSE activities has increased its comparative advantage in the field of national ECD and M&E of PRSPs. Key issues: Regional Context: Development evaluation practices in Africa changed during the 1990’s Lack of development effectiveness despite large amounts of capital inflows in LDCs Inadequate “parachute” approach to evaluate development interventions: need to adopt an “ownership” approach, focusing more on knowledge transfers to national counterparts and national capacity building o Increased need to have national M&E expertise to fully participate in evaluation missions o Increased need to organize existing national expertise in order to strengthen its capacities Constitution of national M&E communities in Africa UNICEF led the way in helping the creation of several national & regional M&E networks/associations: Kenya (1997), Rwanda (1998), AfrEA (1998), Niger (1999). Today, more than 20 networks are active at national level and registered as AfrEA members. 9 Using Internet and ICT to foster evaluation capacities: With little funding available, ICTs were the primary tools used to build these networks. A critical mass of people having access to Internet allowed them to start concrete ECDoriented activities for their communities. Niger Community of Practices at CO level is a key corporate priority that should be linked to M&E as there is knowledge and experiences at the country level (as in the case of ReNSE). This needs to be harnessed and shared as best practices. The Africa Evaluation Guidelines have been amended in accordance with the Nairobi Conference of 2002 to promote the African network in accordance with the guidelines. It is generally felt that this tool is very useful for the quality control of evaluation. Given so many stakeholders and participants in the network, the diversity of involvement does lead to diversity in needs but this is not a problem as it is outweighed by a diversity of expertise. The diversity of expertise is illustrated by the fact that the Steering Committee for the network is made up consultative firms, academia, donor community etc. From the beginning, ReNSE has been open and inclusive as possible for anyone interested in M&E. Although it poses management challenges, each time an action plan needs to be validated it is done in a formal meeting where decisions are made through consensus. The ReNSE has increased the demand for evaluations within government and improved the M&E culture. Evaluation expertise has increased due to the efficacy of the database. More than 60 people work on the database. There is a specific relationship between ReNSE and the PRSP secretariat. Before this, there was a lack of analyses for the M&E component in the PRSP – now, ReNSE is providing expertise in terms of the Log frame development for the PRSP. The Ministry of Economics and Finance in Niger has commissioned ReNSE to help elaborate on their own evaluation standards and to develop an evaluation manual. The co-ordination of ReNSE is a priority task for UNDP Niger – in the new CEPAP specific support to ReNSE is elaborated. Currently, there is debate whether it should be a formal network or is it sufficiently manageable as it is (i.e. informal). Sustainability of ReNSE is a key and UNDP is not the only partner as SWISS and Aide et Action have dedicated specific funds for the network. 10 6. Practices in Monitoring and Evaluation in UNDP: Findings and key issues emerging and overview of country evaluations (ADRs) Presenters: Knut Ostby & Fadzai Gwaradzimba, Evaluation Office The presentation on M&E practices focused on sharing findings on M&E practices at the country level based on recent assessments and several exercises including reviews of outcome evaluations conducted in some countries. The objective was to facilitate an assessment o what was seen to be working and what has not been working, assess why certain things are working, how they working and who the partners that contribute or need to be engaged to move forward in the future. The presentation on the ADR focused on its purpose, its position in UNDP M&E Architecture, scope of the assessment and the process involved. The strength, key lessons, emerging challenges and future direction of ADR were highlighted. The above issues have therefore called for the formulation of new cooperate policies on M&E, improved guidelines, norms and standards, capacity building, better ways of linking M&E to RBM and national Development results and better us of M&E results. Key issues raised during discussion: A question was raised on the timing of the ADR. It was suggested that the ADR should be undertaken at a period when its outcome would contribute and add value to follow-up activities in the Country Office (E.g. The UNDAF Process, formulation of new country programme). There is a need to enhance the consultative process between the Headquarters, Country Offices and other stakeholders in the design and formulation of strategies for the ADR process. Otherwise it will be seen to be a Headquarters driven process. On the design of new M&E policy, emphasis was made on the need to engage other development partners in the development of the broader policy framework. On the continued use of M&E tools by Country Offices that are no longer mandatory, a suggestion was made to look at the broader functionality of some of these tools since new instruments have not been developed and tested to replace the old ones. 7. Experiences with Outcome Evaluations The scale and complexity of national capacity building processes make the development and application of M&E methods and instruments particularly challenging. The purpose of this session was to reflect on different dimensions of outcome and other types of 11 evaluations undertaken by country offices, to review different approaches used, and from the experience of participants, to identify key considerations to take account of in monitoring and evaluating results. Three case studies were presented and key issues are highlighted below: 1) Mali: Outcome Evaluation Applied to Decentralization, presented by Djeidi Sylla, Senior Policy Adviser for M&E, UNDP Mali: The outcome evaluation was very time consuming, 3 months in total, therefore the timeframe needs to be given careful consideration in the overall planning; Partners need to be made aware of M&E issues at the outset of programme intervention and outcome evaluations should include consultations with the widest range of partners - as the outcome depends on their contribution; In Mali, partners did not effectively participate in the evaluation process, and the exchange of information took place only with some difficulty. The above issues have critical implications in terms of how the outcome evaluation feeds into the development agenda of Mali, especially since the outcome is seen as part of the Mali national development process. 2) Zimbabwe: UNDAF Joint Mid-Term Evaluation, presented by Bernard Mokam-Mojuye, DRR, UNDP Zimbabwe: There was a need to redirect the CO development programme to respond to humanitarian challenges in 2002; A joint UN evaluation in all the thematic areas was critical. UNDP had to ensure that there was UN ownership; The outcomes to be achieved with the government were not clear, which posed a major challenge. UNDP Zimbabwe faced two specific problems: Their was lack of understanding of what exactly the different agencies wanted to find out; and secondly, the agencies did not want to rock the boat, as the evaluation had the potential to bring out issues that could not be easily managed. 3) Zimbabwe: Outcome Evaluation on HIV/AIDS, presented by Nancy O’Rourke, Adviser, UNDP Zimbabwe. UNDP is now using a multi-sectoral and multi-level response to HIV/AIDS; UNDP needs to find it’s niche within HIV/ AIDS; There has to be greater clarity on how UNDP works with it’s partners, gain visibility and contribute to added value; There is a need for additional capacity for undertaking outcome evaluation. 12 Key Issues raised during discussion: ROAR is not seen as an integrated system; Culture of learning from the Zimbabwe experience should be encouraged; The Government finally agreed with the UN on the Governance and Human Rights issues. Capacity building of Government departments is essential; The UNCT worked very well. The harmonization of interventions should be encouraged; Outcome evaluations require managing politically sensitive issues with government. We can open a Pandora’s box without being able to effectively address issues. Effectiveness is dealing with achieving the objective, which requires looking at relevant facts. Relevance, on the other hand, is the usefulness of the intervention at a particular time. 8. Contributions for the UNDP Evaluation Policy – Group Work UNDP’s evaluation policy is under development by the Evaluation Office, in close collaboration with country offices and headquarters units, to meet the need for an overarching approach to evaluation in UNDP. Given the country experiences, the current trends in M&E and the proceedings so far at the workshop, the participants were asked to comment on the implications for the future monitoring and evaluation policy. The participants divided into three working groups and discussed three sets of issues related to this subject, as follows: 1. Concept, purpose and participation; 2. Planning, capacity and learning; and 3. Evaluability, evaluative evidence and monitoring The three groups made presentations to the plenary, summarizing their deliberations. Group 1 – Concept, purpose and participation: Group 1 stressed the fundamental Government ownership of the development process and hence of evaluation. The potential to use M&E to shape policy in collaboration with Government was pointed out. In addition to Government, other important partners include the UN agencies, where harmonization of the M&E systems is an issue. For partnerships with donors, private sector and CSOs, partnership dimensions include funding, consultancies, use of M&E findings, participation (CSOs) and how to process the M&E information. For improvement of the M&E function, a key need will be to enhance the Information, Education and Communication (IEC) dimension. This will support achievement of development outcomes, and help engage stakeholders. The extent to which M&E efforts 13 are aimed towards a high strategic level tends to be limited. Constraints include a lack of medium to long term planning, and a low priority given to M&E efforts. The lack of understanding of M&E concepts and the capacity with UNDP and Government to conduct evaluations at the outcome level are also limiting factors. There is also a need to strengthen the linkages between UNDP’s RBM process and national planning processes. Finally, it was noted that there is a need for institutional learning, but that UNDP still has a long way to go to assign an adequate priority for this important area. Limited resources are not matching learning requirements, and time management for learning is poor. Group 2 – Planning, capacity and learning Group 2 highlighted the range of tools available to COs in strategic planning. A core entry point is the comprehensive process around the UNDAF results matrix. This process takes a string point in country priorities and targets, including MDGs, and goes through an overall UN country team planning process to lead to individual agency country programmes and CPAPs. In UNDP, this in turn links to the MYFF and SRF processes, and through annual work plans the goals are linked to the Atlas results/project tree. This comprehensive system of planning and monitoring also facilitates evaluation, learning and are key to capacity building, allowing UNDP and other agencies to offer support to host governments in this regard. The groups stressed the importance of working with the host government as the main partners for all parts of these efforts. Other dimensions of learning include exchanges among UNDP’s country office. These offices are each other’s best support in terms of capacity and sharing of lessons learned. Exchanges have included methodologies as well as people with expertise to offer, or with a need to learn. Group 3 – Evaluability, evaluative evidence and monitoring To strengthen evaluability, Group 3 stressed the need for a clear understanding of the problem, for a comparative and objective analysis. The parameters of intervention need to be clear, and baselines, indicators and benchmarks need to be S.M.A.R.T. Partnership arrangements and the role of various partners should be clearly identified from the design stage. A stronger body of evaluative evidence would be enhanced by an effective participation of stakeholders. The size and nature of the sample needs to be adequate, and establishment of proxy measures as well as comparative analysis could broaden the coverage. It is important not only to draw on own sources, but also to use external reports and surveys from government, civil society, private sector etc. When undertaking monitoring, it is important that the purpose and overall goals are understood, i.e. that it covers both a learning and an accountability dimension. The RBM approach to monitoring helps performance assessment as well as strategic management. 14 In the case of monitoring as well as evaluation, it is important to budget the required resources at the programming stage, to ensure sufficient quality and coverage of M&E later on. Summary of Concluding Points and Issues from Group Work and Plenary Discussion: UNDP should build on opportunities from emerging trends and support national institutions as well as networks to drive M&E and accountability processes. It should support transformation of a multiplicity of institutions into single credible and independent evaluation entities that can provide oversight and accountability over public policy. M&E systems are not only in need of strengthening for UNDP and Government, but also vis-à-vis NGOs, other civil society groups and private sector. To strengthen evaluative evidence, there has to be effective partnerships and participation of stakeholders to address questions of perception and subjectivity. Engagement of other agencies as source of information for validation needs to be taken more seriously for comparative analysis. Capacity considerations are critical. Our group talked about monitoring and evaluation for our office and government – but what is missing is our These have a bearing on outcomes. M&E capacities exist in the South. Asymmetries between international and national knowledge systems must be bridged. The evaluation function should be brought closer to the country level, and a comprehensive strategy for M&E capacity building should be developed. The issue of resourcing the M&E function needs to be addressed. There is a need for robustness and better alignment in M&E tools and methods. On evaluability, one has to have a clear conceptual understanding on the planning part – on what to do, problems to be addressed, objectives, clear parameters and consider options; benchmarks and good indicators (SMART). The question on how to evaluate “soft assistance” (advocacy capacity upstream work) should be addressed. Whilst looking at monitoring, we need a clear understanding of the purpose of the monitoring system and the purpose of the collection of data or information. If these are clear, then the rest gets simpler. RBM is helpful in this respect. UNDP can add value through designing and conducting ‘real-time’ evaluations of human development issues through new approaches, including participatory methods and local knowledge sharing and learning. Evaluation utilization is critical, to ensure that we build on best practices and strengthen development effectiveness. A strategy is needed for dissemination of M&E results. 15 9. Wrap-up Session: Moving forward, summary of key issues emerging from the workshop Ms. Saraswathi Menon, EO Director, made concluding remarks at the end of the twoday workshop. She noted that some myths had been shattered during the workshop: The first has to do with what was recently mentioned by a member of DAC --- that only donors are interested on M&E given that they are fund givers. The second was that capacities do not exist in our offices and nationally to the level we want. She noted that this workshop demonstrates clearly that there is much more going on than we know. A third myth related to the idea that we need to develop our own M&E system before we can share it with partners. This is a wrong approach since UNDP can never develop an M&E system unless it reaches out and shares its ideas early with external partners. Ms. Menon concluded that, based on the demolition of these myths, UNDP needed to look ahead through a specific prism: What are the key issues? And what are the actions? UNDP needs to focus on development effectiveness, otherwise it will not be able to do relevant monitoring and evaluation. This can not be a ‘stand alone’ process --- but needs to be intrinsically linked to the organization’s substantive work. On some specific issues, she called for further feedback from participants as follows: M&E Support: EO needs to create a much more responsive support system for undertaking M&E --- which could be done through working with the Regional Centers. This needs to be discussed with the Bureau. EO will need to work on this more systematically --- and needs feedback on the kind of support country offices want to get from the regional centre. Further, country offices were asked to provide the EO with their assessment of consultants that were recommended by the Evaluation Office. Focus on knowledge management issues: There is now the EVALNET. Country offices were asked to indicate how useful they find it, and to what extent they rely on it for credible information. Ms. Menon posed the question whether there is a need to go beyond EVALNET – for instance through the RR NET registry? The Evaluation Resource Centre (ERC) – country offices are expected to upload theirr evaluations onto this site. It is not intended to simply post plans but for the COs to draw lessons. The question is whether the COs are able to do this? Are there other suggestions? Codification should be considered – if the EO were to distribute the presentations from this workshop, would it be too much to ask the COs to write it up in 4-5 pages to facilitate circulation? The COs would need to think about what it is that they would like the EO to codify. On capacity development – The EO would want to see what the UNEG comes up with. UNFPA, for instance, has done more than UNDP in this area and they have an interesting way of dividing capacity-building. 16 Methodology – the Evaluation Office is in the process of developing a methodology centre that will try to get a group of academics to work on specific issues. Suggestions from country offices on key issues were requested. Key Issues Emerging From the Workshop Key issues that emerged from the deliberations, including next steps that the country offices expect to carry forward in collaboration with EO, may be summarized as follows: Capacity and resources: There is a need to foster M&E culture within country offices and to allocate more funding towards M&E activities in order to overcome the current lack of evaluative evidence. The participants agreed to give priority to supporting the learning process of M&E by strengthening their learning plan, innovating new approaches and making it “everybody’s business” -- as opposed to creating a ‘focal point’, although a suggestion was made that the DRR could be assigned to oversee M&E activities. Crisis countries: It was recognized that M&E is specifically difficult to undertake in a crisis country; some restructuring is needed where M&E has to be at the centre of UNDP’s interventions in crisis countries. Monitoring: It needs to be taken much more seriously, particularly among government and other national development agencies [“It should not be just a talk show”]. Findings, decisions and agreements need to be followed up more rigorously in terms of their implementation, and relevant bodies, desk officers, supervisors expected to work in M&E have to be better targeted in future. Promoting the culture of learning: (i) M&E profile of individuals need to be reviewed to enhance the effectiveness and use of evaluations; (ii) Evaluation reports should be used to enhance UNDP’s posture on M&E – rather than treating it only as a programme issue;; (iii) There should be more concerted effort to undertake outcome evaluations; (iv) EO could collaborate with OHR to deepen the culture of M&E. Explore relationship between RBM tools and national framework: Countries that have developed an M&E system need to review what is lacking in terms of the implementation of the plan. M&E needs to be more closely linked to the instruments of the MYFF intermediate outcomes or core results. UNDP needs to develop “more space” for informal discussions to strengthen M&E practice: Currently the “space” for discussions is lacking despite the many UNDP networks. Future corporate M&E events need to include UN agencies and more government partners. More engagement with government representatives is critical to fully integrate UNDP’s M&E systems with those of government. There are issues with regional variations that need to be addressed. Also, given that 17 quality of evaluations is generally poor, there is a need to set basic minimum standards. EO support to Country Offices for introducing results-oriented instruments and approaches: In a number of countries, UNDP is undergoing an ambitious process of change (e.g. UNDP Tanzania dialoguing with government on setting up a results based monitoring system within the government; while some other countries are trying to work out the best modality for introducing results-oriented tools and instruments, procedures and on how to assess progress). The country offices of Mali, Niger, Tanzania and Uganda specifically expressed a desire to partner with the Evaluation Office to improve their M&E initiatives. Dissemination of best practices: In spite of lack of capacity in general, there are many excellent practices in the Africa region, and in other regions as well. Also, strong expertise and capacities exist in a number of COs and their partners. What is lacking is codification and dissemination of these best practices and knowledge. There is a special role for EO to facilitate an improved process for such codification and dissemination in future. 18