Paper (MS Word) - Hunter College

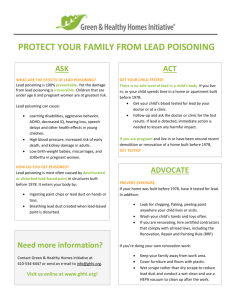

advertisement

Trends in Lead Exposure in New York City: Challenges and Implications for Public and Environmental Health Policy and Practice Working Draft June 9, 2000 To Be Presented at: The Second Annual Seminar on Comparative Urban Projects Centro Interdipartimentale di Studi e Ricerche sulla Popolazione 3 la Società Università degli Studi di Roma “La Sapienza” and Hunter College City University of New York Rome, June 19-23, 2000 Susan Klitzman DrPH, Associate Professor Environmental and Occupational Health Sciences Urban Public Health Program, School of Health Sciences Hunter College 425 East 25th Street New York, New York 10010 212-481-5155 sklitzma@hunter.cuny.edu Childhood Lead Poisoning Prevention at the Crossroads Over 8000 years after lead was first discovered, it still remains a significant environmental health threat today. Lead has been mined, produced and used around the world for over 4000 years1. It had widespread usage during the Roman era – especially for pipes, roofing, eating and cooking materials and maritime applications2 The Romans were also among the first to recognize the dangers of lead poisoning (during smelting) some 2000 years ago.3 In the United States, knowledge of the health hazards of lead can be traced back to the 19th century4. Today, lead poisoning is considered to be totally preventable condition: the cause is clearly defined; the source is exogenous to the individual (unlike intrinsic, or genetic causes of disease); and exposure is the result of human activity (unlike naturally occurring contaminants or dangers, over which humans can exert little control). In spite of our long-standing knowledge of the dangers of lead, significant efforts to monitor and control it in New York City (as well as in the United States) are relatively recent . For example, it was only in 1970 that the New York City Department of Health (DOH) first established a childhood lead poisoning prevention program. Since that time, New York City has experienced dramatic declines in the incidence of childhood lead poisoning5 . The trends are consistent with national data6. This public health success did not occur spontaneously or through ‘natural’ market forces, but rather, was the result of concerted and sustained advocacy on the part of public health, housing, environmental, academic, community, and legal organizations and government agencies at the national, state and local levels – often in the face of fierce opposition from lead-using and producing industries3,7. Despite overall population declines in lead poisoning, many children continue to be at risk for high-dose lead exposure. Children who are very young, poor, African and Caribbean American, Latino, living in large urban areas and living in older housing, both in New York City as well as in the nation, are disproportionately affected6. Currently, the major remaining source and pathway of lead exposure to young children is ingestion of dust and paint chips from deteriorating, lead based paint, especially in older, dilapidated urban housing.8 Earlier this year, the U.S. Surgeon General set a national goal to completely eliminate elevated blood lead levels (defined as 10 micrograms per deciliter – μg/dL) in children by the year 20109. Attaining this goal will require that residential lead paint hazards are controlled before a child becomes lead poisoned. This may appear to be a simple and logical concept, but it is one which has been fraught with significant economic, political, and 1 legal obstacles in its implementation. Given the significant progress which has been made to date, and the challenge before us in the coming decade, this is an opportune time to analyze the factors responsible for success and to reflect on the new strategies which will be needed to achieve the Surgeon General’s goal. Lead in the environment Lead is a naturally-occurring metal, which is still mined in several states throughout the U.S. (as well as throughout the world). It can combine with other chemicals to form lead compounds and lead salts. Lead and lead compounds have been used in the past (and in some cases are still being used) in many common industrial, commercial and consumer products both in the United States and around the world. These products include: paint, gasoline, batteries, ammunition, metal products (e.g. solder, sheet metal, pipes, brass and bronze products), ceramic glazes, medical equipment (e.g. radiation shields for protection against X-rays, fetal monitors, surgical equipment), and scientific equipment (e.g. circuit boards for computers) and military equipment. Some of the properties which have rendered it commercially important include: high density, low melting point; ease of fabrication and casting; acid resistance; chemical stability in air, water and soil; and electrochemical reaction with sulfuric acid10. Because of its widespread usage by human beings, lead is now ubiquitous in our environment. Small amounts can be found in air, water, soil, dust, food and in living organisms (plants, animals and humans)10. Exposure is concentrated, however, in older urban centers in the United States – owing to such factors as higher concentrations of traffic, and older, dilapidated housing containing peeling lead-based paint. The main pathways through which humans can be exposed to lead are from breathing in or ingesting lead-containing dust or fumes. Exposure to lead has been shown to damage the nervous, hematopoietic, endocrine, renal and reproductive systems of the body10. Toxic effects become more pronounced with increasing concentrations of lead in the bloodstream.. Over the years, research has documented adverse effects of lead at levels previously thought to be safe11. Children are especially vulnerable to lead-induced health effects for several reasons. Children under age 5 absorb more lead through the gastrointestinal tract (50% relative absorption) than adults (15% relative absorption)12.Also, who have nutritional deficiencies (such as zinc, calcium and iron deficiency) may be at increased risk because these deficiencies may exacerbate absorption and toxicity of lead10. Toddlers also have a greater frequency of normal hand-to-mouth activity and thumb-sucking, which puts them at greater risk of ingesting leadcontaminated dust and dirt13. That very young children consequently have higher blood lead levels than older children and adults has also been well-documented through epidemiologic surveillance . 2 The Epidemiology of Childhood Lead Poisoning Historic Trends: Over the past 3 decades, there has been a dramatic decline in both the magnitude and severity of childhood lead poisoning in New York City. In 1970, when DOH first organized a childhood lead poisoning prevention program, 2,649 cases of childhood lead poisoning were diagnosed at the then-current action level of 55 μg/dL. In 1998, there were 1072 newly diagnosed cases at the action level of 20 μg/dL, a reduction of about 60% (see Figure 1). Between 1998 and 1999, the incidence declined another 15% – to 895 cases14. 1. Krysko WW, Lead in History and Art, Verlag: Stuttgart, 1979. 2. Lansdown R and Yule W, Lead in history in The Lead Debate: The Environmental, Toxicology and Child Health, London: Croon Helm, 1986. 3. Kitman JL, The secret history of lead. The Nation, 270(11), March 20, 2000: 11 - 44. 4. Stewart MD, Notes on some obscure cases of poisoning by lead chromate manifested chiefly by encephalopathy, Medical News 1, 1887: 676-681. 5. Klitzman S and Leighton J, Decreasing childhood lead poisoning in New York City: 19701998, Journal of Urban Health, 76(4),: December 1999: 542-545. 6.US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Update: Blood lead levels – United States, 1991 - 1994, MMWR 46(07), February 21, 1997: 141-146. 7. Markowitz G and Rosner, “Cater to the children”: The role of the lead industry in a public health tragedy, 1900-1955, AJPH, 90(1): January 2000, 36-46. 8. President’s Task force on Environmental Health Risks and Safety Risks to Children, Eliminating childhood lead poisoning: A federal strategy targeting lead paint hazards, February 2000. 9. US Department of Health and Human Services, Healthy People 2010, March 2000. 10. Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry, Toxicological Profile for Lead (Update), July 1999. 11. US Centers for Disease Control, Preventing lead poisoning in young children, October 1991. 12. Chamberlain A, Heard C, Little P et al. Investigations into lead from motor vehicles. Harwell, United Kingdom: United Kingdom Atomic Energy Authority. Report no. AERE-9198. 1979. The dispersion of lead from motor exhausts. Philos Trns R Soc Lond A 290: 557-589, 3 1978. 13. Schroeder SR, Hawk B, Psychosocial factors, lead exposure and IQ. Monograph of the American Association of Mental Deficiencies, 1987, S:97-137. 14. New York City Department of Health, Lead Poisoning Prevention Program, unpublished data, 2000. 4