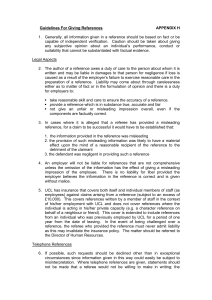

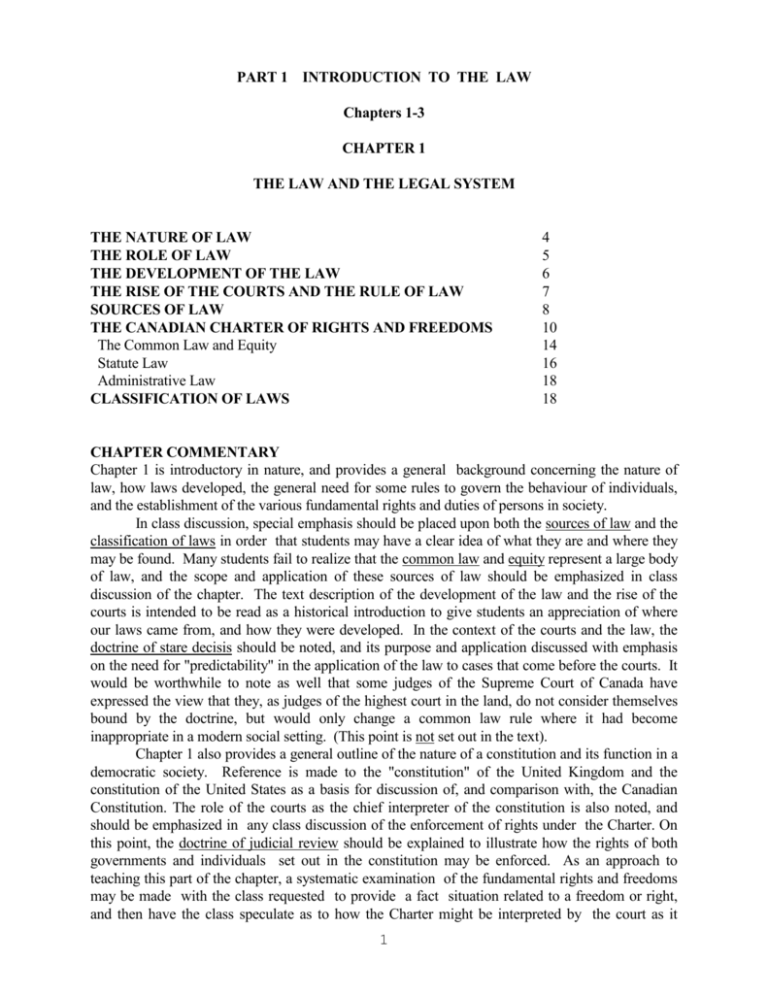

chapter commentary

advertisement