Module 9 –D Vital Signs: Blood Pressure

Learning Supplement

Vital Signs – Blood Pressure

Introduction

Blood pressure is a measure of the pressure exerted by the blood on the walls of an artery as it flows through the arteries. Blood flows throughout the circulatory system because of pressure changes. It moves from an area of high pressure to an area of low pressure. The heart as it contracts forces blood under high pressure into the body.

Because blood moves in waves, there are two blood pressure measures:

1. Systolic pressure – the pressure of the blood as a result of contraction of the ventricles, that is the pressure of the height of the blood wave.

2. Diastolic pressure – the pressure when the ventricles are at rest. Diastolic pressure is the minimal pressure exerted against the arterial walls at all times.

The difference between the systolic and diastolic pressure is the pulse pressure.

The average normal blood pressure range of an adult is: systolic varies from

100 – 140 mm. Hg. Diastolic ranges from 60 to 90 mm. Hg.

Physiology of Blood Pressure

Blood pressure reflects the relationship of cardiac output, peripheral vascular resistance, blood viscosity, and artery elasticity. a. Cardiac Output – the volume of blood pumped by the heart (stroke volume) during 1 minute (heart rate). CO = HR X SV.

The blood pressure (BP) depends on the cardiac output (CO) and peripheral resistance (R): BP = CO X R

When volume increases in an enclosed space, such as a blood vessel, the pressure in that space rises. Thus, as cardiac output increases, more blood is pumped against arterial walls, causing the blood pressure to rise. Cardiac output can increase as a result of an increase in heart rate, greater heart muscle contractility, or an increase in blood volume. b. Peripheral Vascular Resistance – Blood circulates through arteries, arterioles, capillaries, venules, and veins. Arteries and arterioles are surrounded by smooth muscle that contracts or relaxes to change the size of the lumen. The size of arteries and arterioles changes to adjust blood flow to the needs of local tissues. For example, when more blood is needed by a major organ, the peripheral arteries constrict, decreasing their supply of blood. More blood becomes available to the major organ. Peripheral vascular resistance is the resistance to blood flow determined by the tone of vascular musculature and diameter of blood vessels. The smaller the lumen of a vessel, the greater the resistance to blood flow. As resistance rises, arterial blood pressure rises. As vessels dilate and resistance falls, blood pressure drops. c. Blood volume – the volume of blood circulating within the vascular system affects blood pressure. Most adults have a circulating blood volume of 5000 ml. Normally the blood volume remains constant. If the volume increases, more pressure is exerted against arterial walls

and elevates blood pressure. When circulating blood volume falls, as in hemorrhage blood pressure falls. d. Viscosity – the thickness of blood affects the ease with which blood flows through small vessels. The hematocrit or percentage of red blood cells in the blood, determines blood viscosity. When the hematocrit rises and the blood flow slows, arterial blood pressure increases. The heart must contract more forcefully to move the viscous blood through the circulating system. e. Elasticity – as pressure in the arteries increases, the diameter of the vessel walls increases to accommodate the pressure change. When the vessel wall lose their elasticity and are replaced by fibrous tissue that cannot stretch well, there is greater resistance to blood flow and blood pressure rises. When a given volume of blood is forced through the rigid arterial walls, the systemic pressure rises. Systolic pressure is more significantly elevated than diastolic pressure as a result of reduced arterial elasticity.

Each of the above factors affects the other. As arterial elasticity declines, peripheral resistance increases.

Factors Influencing Blood Pressure

1. Age

2. Stress and emotions

3. Gender

4. Medications

5. Disease

6. Body position and exercise

Hypertension / Hypotension

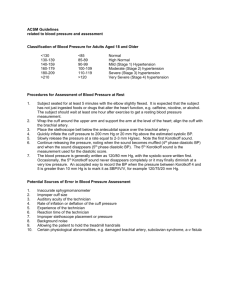

Normal blood pressure is classified as systolic BP <120 mm. Hg. and diastolic BP

<80 mm.Hg. Prehypertension is BP 120-139/80-89.

Hypertension is an elevated blood pressure. Hypertension is diagnosed in adults when two or more diastolic readings on two different visits is 90 mm. Hg. or higher or when the systolic reading is 140 mm. Hg. Hypertension is a contributing factor to myocardial infarctions and strokes. It is often asymptomatic. It is associated with increased viscosity and decrease in elasticity in the arterial walls.

Hypotension is a lowered blood pressure. It is present when the systolic pressure falls to 90 mm. Hg. or below. Hypotension occurs because of the dilation of vessels, the loss of a substantial amount of blood volume, or the failure of the heart to pump adequately.

Both of these abnormalities in blood pressure can be life threatening and should be reported to the doctor immediately.

Assessment of Blood Pressure

Blood pressure can be measured either directly or indirectly.

The direct method requires the insertion of a thin catheter into an artery that is connected to electronic monitoring equipment. The monitor displays constant blood pressure readings. This is used mainly in intensive care units.

The indirect method is more common and measures blood pressure by auscultation or palpation. Auscultation is more common.

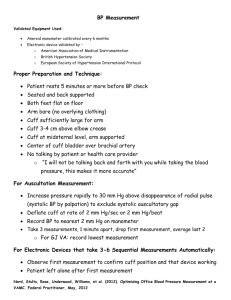

Equipment

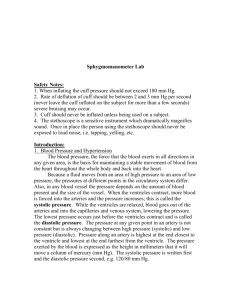

The two main equipment items are a sphygmomanometer and stethoscope.

1. A sphygmomanometer comprises a pressure manometer, a cuff that encloses an inflatable rubber bladder, and a pressure bulb with a release valve to inflate the cuff. The original sphygmomanometers were mercury

(that’s why BP is recorded as “mm. Hg..” ) The aneroid sphygmomanometer or the electronic are the most common in use now. The aneroid manometer has glass-enclosed circular gauge containing a needle that registers millimeter calibrations. A metal bellows within the gauge expands and collapses in response to pressure variations in the inflated cuff. The needle should fall as pressure is released and should always be at zero when the cuff is deflated.

Cuffs used with the sphygmomanometer come in several sizes. The size is selected according to the circumference of the patient’s limb being used to assess the blood pressure. The width of the cuff should be 20% greater that the diameter of the extremity on which it will be used. It should be long enough to encircle the extremity completely. An improperly fitting cuff causes inaccurate blood pressure readings.

Before using a sphygmomanometer, the nurse should check all the parts to be sure they are working correctly.

2. Stethoscope – used to hear the sounds on which you base your blood pressure measurement. Be sure the earpiece tips point toward the nose, not the back of the head. Have the environment quiet.

Auscultation

Auscultation of blood pressure begins with the patient in a comfortable position and the arm unrestricted by clothing. Using the aneroid sphygmomanometer, the nurse should be focused on the gauge. The most common site used is the brachial artery.

The indirect method of auscultation works on a basic principle of pressure. Blood flows freely through an artery until an inflated cuff applies pressure to the artery partially obstructing blood flow. After the cuff pressure is slowly released, turbulent blood flow blood flow vibrates the walls of the artery producing sounds. When all the pressure is released, the sound disappears.

After applying the diaphragm of the stethoscope over the brachial artery, the nurse will first hear no sound. Then,

1. The first sound is a clear rhythmical tapping corresponding to the pulse rate that gradually increases in intensity. Onset of this sound is the systolic

pressure.

2. This sound increases in intensity, finally tapering off.

3. As the cuff is further deflated, the sounds become more muffled and low

pitched.

4. Finally, the point at which no sound is heard, is the diastolic pressure.

Palpation

The indirect palpation method is used for patient’s whose arterial pulsations are too weak to create audible sounds. The only reading available through palpation is the systolic pressure.

Both methods must be documented appropriately and as soon as the reading are obtained.

Alternative Sites

If the upper arms are not available for assessing blood pressure, then the lower extremities may be used. The popliteal artery behind the knee is used on the leg.

Alternative Devices

Electronic devices are available to automatically assess blood pressure. Once the blood pressure cuff is applied, the nurse can program the device to obtain and record blood pressure readings at preset intervals. Alarm parameters can be set. These are used when repeated and frequent blood pressures are needed, as in a postoperative patient. Automatic devices are more sensitive to interference and are susceptible to error.

Common Errors in Measurement of Blood Pressure

Error

Bladder or cuff too wide

Bladder or cuff too narrow

Cuff wrapped too loosely

Deflating cuff too slowly

Deflating cuff too quickly

Stethoscope that fits poorly or impairment of examiner’s hearing, causing sounds to be muffled

Inaccurate inflation level

False low reading

Effect

False high reading

False high reading

False high diastolic reading

False low systolic and false high diastolic reading

False low systolic and false high diastolic reading

False low systolic reading

Procedure for Assessing Blood Pressure

Refer to Harkreader, Procedure 7-5, pp. 132-134.

IV. Learning Activities

1. Practice with a partner taking blood pressure by auscultation and palpation.

2. Practice assessing blood pressure on several different people in lab – comparing lying, sitting, standing.

3. With an instructor or another student, use the doubled-eared stethoscope and take the B/P on several students.

4. Document appropriately.