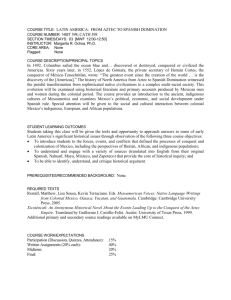

Epistemic Disobedience and the Decolonial Option

advertisement