Independence movements in the Caribbean: withering

advertisement

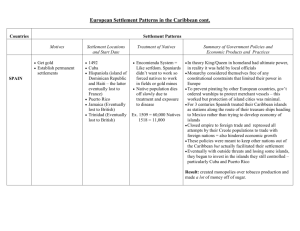

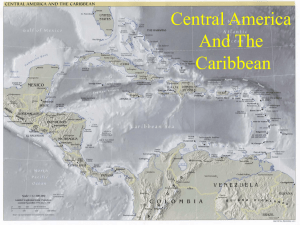

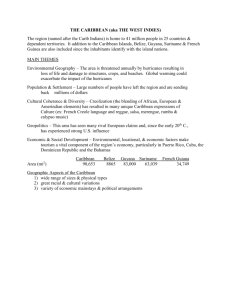

Independence movements in the Caribbean: withering on the vine? Peter Clegg *Paper prepared for the international workshop, “Island Independence Movements in the 21st Century,” University of Edinburgh, Scotland, 8-10 September 2011 Introduction A number of countries in the Caribbean region have yet to gain independent status. They still maintain constitutional relationships, albeit under different systems, with their original metropolitan powers, be it the United Kingdom (UK) Overseas Territories, the six countries linked to the Netherlands, the United States (US) controlled Puerto Rico and US Virgin Islands, or Guadeloupe, Martinique, Saint-Barthélemy and Saint-Martin which are part of France. There is also Nevis (of St Kitts and Nevis) which has hosted strong secessionist sentiments. However, at the present time none of the islands wish to stand on their own as sovereign states, despite politicians in several of them initiating moves towards independence in the fairly recent past. This paper evaluates these attempts and explains why they failed, as well as detailing briefly why independence on certain islands has never been a significant issue. Notwithstanding, many governments and political parties of the islands challenge the status quo, and thus there has been debate over the extent to which greater autonomy (even if not full independence) can be provided to them. While the metropoles have been generally willing to grant more autonomy, a situation is now developing whereby further change is increasingly unlikely, and in some cases there has been a moderate repatriation of powers. The paper thus also considers the nature of the political relationships in place, the reforms that are being undertaken in an attempt to re-energise and reorganise links, and why it is possible that an end point is being reached in the awarding of further autonomy. The United Kingdom Overseas Territories The collapse of the Federation of the West Indies precipitated a period of decolonisation in the English-speaking Caribbean, which began with Jamaica and Trinidad and Tobago in 1962. By the end of 1983, British colonial responsibilities in the Caribbean extended to only five very small Territories – in fact the five territories that remain under UK authority today. Bermuda located in the West Atlantic stayed also under UK control. Despite the trend towards self-rule, several of the smaller British territories were reluctant to follow suit. As a consequence, the UK authorities had to establish a new governing framework for them. This was required as the West Indies Federation had been the UK’s preferred method of supervising its Dependent (now Overseas) Territories in the region. In its place, the UK established constitutions for each of those Territories that retained formal ties with London. The West Indies Act of 1962 (WIA 1962) was approved for this purpose and it remains the foremost provision for five of the six OTs. The sixth, Anguilla, was dealt with separately owing to its long-standing association with St Kitts and Nevis. When Anguilla came under direct British rule in the 1970s and eventually became a separate Dependent Territory in 1980, the Anguilla Act 1980 (AA 1980) became the principal source of authority. The constitutions of the territories framed by WIA 1962 and AA 1980 detail the complex set of arrangements that exist between the UK and its OTs. Because, with the exception of Anguilla, the relationship between the territories and the UK is framed by the same piece of legislation, there are organisational and administrative similarities. Each 1 constitution allocates government responsibilities to the Crown (i.e. the UK government and the governor) and the OT, according to the nature of the responsibility. Those powers generally reserved for the Crown include defence and external affairs, as well as responsibility for internal security and the police, international and offshore financial relations and the public service. The Crown also has responsibility for the maintenance of good governance. Meanwhile, individual territory governments have control over all aspects of policy. However, ultimate control rests in the hands of the UK as the territories are constitutionally subordinate (Davies, 1995), and as a consequence they are considered to be ‘non-self-governing’ (Corbin, 2011: 2). Despite the many similarities, there are several differences in the local constitutions. The constitutions of Montserrat, British Virgin Islands (BVI), and particularly Bermuda afford greater executive and legislative autonomy than those of Anguilla, Cayman Islands, and Turks and Caicos Islands (TCI). To a large extent, this is due to the fact that the former three Territories were never dependencies of other colonies. They have been administered either as colonies in their own right, or as a part of wider groupings such as the Federation of the Leeward Islands, or (for Montserrat) as a part of the Federation of the West Indies. The differences in relative constitutional power and the associated level of political maturity have played a role in framing the attitude of territories towards independence. For example, both Bermuda and Montserrat have come quite close to gaining independence, although the TCI has also pushed for independence. Of the other territories (Anguilla, BVI, and Cayman Islands) there has been little serious demand for independence because of their political conservatism and/or dependence on ‘American money’ and ‘British security’ (Connell, 1997: 40). For the three Territories that have come closest to achieving independence, it was public disapproval, serious concerns over the standard of local governance, and/or natural disasters which have largely prevented the successful completion of the process. Montserrat In the case of Montserrat, then Chief Minister John Osborne who headed the People’s Liberation Movement (PLM), came out strongly for independence in the early 1980s. A key reason was Montserrat’s exclusion from participating in the US-led invasion of Grenada in October 1983 (Fergus, 1989: 146). Other members of the Organisation of Eastern Caribbean States (OECS) were involved in the planning and execution of the invasion but because Montserrat was a Dependent Territory it needed the green-light from the UK government which was not forthcoming. As Fergus noted, this outcome ‘embarrassed Osborne’ and highlighted his inferior position in relation to his OECS colleagues (1989: 146). Despite strong opposition amongst some in Montserrat, there was a belief that a formal move towards independence should then take place. However, three events damaged severely Montserrat’s quest. First, in 1989 a serious banking scandal was uncovered which implicated most of the islands’ banks in money laundering (Fergus, 1990: 57). In response, the UK government re-wrote Montserrat’s constitution to ensure the Governor would in future have supervisory power over the island’s international financial affairs (Fergus, 1990: 58). These developments undermined the credibility of the government and Chief Minister Osbourne, and strengthened the UK’s hand over the territory. Second, and also in 1989, Montserrat suffered considerable damage as a result of Hurricane Hugo. To ameliorate the situation, significant aid was provided, causing Osbourne himself to admit that with greater dependence on the UK for the foreseeable future, independence was not really an option (Davis, 1995: 43). Third and perhaps most importantly were the devastating effects caused by the eruption of the Soufrière Hills Volcano which began in July 1995. By December 1997, almost 90 per cent of the resident population of over 10,000 had been relocated at least once, while over two-thirds had left the island. Much of the infrastructure had been destroyed or put out of use, while the private 2 sector had collapsed and the economy had become largely dependent on British aid (DFID, 1999). Montserrat still receives considerable UK assistance: for 2010-11, this amounted to £20 million (Caribbean Insight, 2010a: 10). Bermuda In Bermuda the first talk of independence came in the mid-1960s. In the 1968 general election, the Progressive Labour Party (PLP), strongly supported by black Bermudans, called for independence. However, the election was lost to the United Bermuda Party (UBP) which enjoys the support of most white Bermudans. However, once in power ‘… the UBP began to contemplate the possibility of independence, when Britain dissolved the sterling area and broke monetary ties to Bermuda’ (Connell, 1997: 42). Nevertheless, the issue remained on the back-burner until disaffection among young blacks led to race riots in December 1977, sparked off by the execution of two men found guilty of the 1973 assassination of Governor Richard Sharples. The subsequent Royal Commission appointed to enquire into the unrest recommended that Bermuda should be brought to early independence in part to provide full emancipation and a sense of belonging to black Bermudians (Davies, 1995: 13). However, in both political parties, there was significant opposition to independence and it was not an issue in the elections held between 1980 and 1993. Notwithstanding and rather unexpectedly Sir John Swan of the UBP (and the first black premier back in 1983), announced that a referendum would soon be held. Swan highlighted the profound changes to the international political economy that were occurring, for example the creation of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), and local developments including the closure of the British and US bases. Under these circumstances Swan felt that the country needed to decide its constitutional future (Connell, 1997: 43-44). A referendum on independence was duly held on 15 August 1995, but over 70 per cent of the electorate voted against. Swan resigned and the issue was left to one side for almost a decade. However, the independence debate was re-opened in 2004. The PLP took the initiative after being emboldened by election victories in 1998 and 2003. A Bermuda Independence Commission was established which published its findings in September 2005. While the report did not recommend or oppose independence, it concluded that Bermuda could afford the associated costs but raised questions over nationality and race, amongst others (Bermuda Independence Commission, 2005). In March 2007, Premier Ewart Brown declared that independence was ‘inevitable’, but a July 2007 opinion poll recorded 63 per cent of respondents opposed to independence, 25 per cent in favour and 12 per cent undecided (Jane’s, 2009). So even though Bermuda has a decently sized population of just below 70,000; a high GDP per capita figure of US$91,477 (2007 figure) (Bermuda Department of Statistics, 2009: 7); and a large part of the population who feel somewhat marginalised, the status quo of substantial autonomy on the one hand and a degree of political, legal and economic security via the UK on the other remains the preferred system of governance. The will of the people has so far thwarted the drive to full independence. 3 Turks and Caicos Islands In the TCI, there have been two occasions when the issue of independence has been raised, but local government corruption and maladministration have stopped any progress in its tracks. The first time was between 1976 (when the TCI gained its first separate constitution) and 1980. During this period, the mildly populist People’s Democratic Movement (PDM) led by the charismatic James (JAGS) McCartney was interested in seeking full internal selfgovernment (Connell, 1997). However, the UK government was unwilling to allow such reform unless the TCI then moved to independence. The PDM duly accepted this and it was agreed that internal self-government would be granted in early 1981, with independence following soon after (Connell, 1997: 41). However, the PDM lost the 1980 election in part because its leader died in a plane crash just before and the party had been tarnished by ‘… widespread allegations of corruption and ineptitude’ (Thorndike, 1987: 261). The result was that the opposition Progressive National Party (PNP) won the election and it felt that the TCI was not yet ready for independence. Ironically it was under the PNP’s watch that any chance for independence during this period was ended with the imprisonment in the US of former Chief Minister Norman Saunders and two other PNP members on drugs related charges in 1985, and then the imposition of direct rule from London in 1986 after further serious allegations of corruption and subversion of the state by members of both political parties came to the fore (Cichon, 1989; Report of the Commissioner Mr Louis Blom-Cooper QC, 1986). It was not until 1988 that self-government was returned to the Territory. In the mid-2000s, under the premiership of Michael Misick of the PNP, the issue of full internal self-government and independence was revisited. In April 2006, Misick stated that the PNP saw independence from the UK as the ‘ultimate goal’ for the islands (Caribbean Net News, 2006). However, once again any possibility of moving towards independence was ended by serious allegations of corruption and mismanagement. A detailed picture of the state of affairs was revealed by a Commission of Inquiry led by Sir Robin Auld, who recommended the institution of criminal investigations in relation to Misick (who resigned as premier in March 2009 after the Commission’s interim report was published) and three of his former cabinet ministers (TCI Commission of Inquiry, 2009). In August direct rule from London was once again introduced, and the UK government is now undertaking the difficult process of rebuilding the TCI’s political reputation. However, it is clear that when selfgovernment is returned, there will be a ‘greater British presence’ in the TCI (Caribbean Insight, 2010b: 11). Constitutional revision So for Montserrat, Bermuda and TCI, the quest for independence has so far been thwarted. However, that does not mean that the relationship between the UK and the OTs is static. First, constitutional review is an ever present concern. For Bermuda, for example, there have been constitutional changes in 1968, 1973, 1979, 1989, and 2003. More recently, in 2001, the UK government set in motion a constitutional review process for the OTs. However, the government had clear lines beyond which reform was not possible, particularly in relation to its reserved powers, the independence of the judiciary and the impartiality of the civil service (Foreign Affairs Committee, 2004: 7). So in the constitutions agreed recently for the BVI, the Cayman Islands, Montserrat, and the TCI (now partially suspended), only limited new responsibilities were devolved to the territories. Second, the relations between the UK and the territories can be very fractious. Recent examples of serious disagreement include the UK’s decision to impose legislation to decriminalise homosexual acts between consenting adults in private (2001); the implementation of the European Union’s Savings Tax Directive 4 (2005); and the acceptance by Bermuda of four Guantánamo detainees without the UK government’s prior knowledge (2009). These and other issues have negatively impacted on relations but have not reignited the debate about independence because overall the constitutional link with the UK retains its popularity. Nevis Although a majority of this paper is concerned with island territories that remain under the control of their original ‘colonial’ power, this section deals with an island that is part of a larger sovereign state: Nevis which is part of St Kitts and Nevis. The tensions between Nevis and St Kitts go back as far as 1882 when the British united them (with Anguilla) for administrative purposes (Midgett, 2004: 45). In the modern era serious problems began with the awarding of Associated Statehood to St Kitts-Nevis-Anguilla in 1967, and the latter’s messy departure from the three island state soon after (Byron, 1999). Anguilla’s concern about being part of a unitary state dominated by the government in St Kitts was shared by Nevis. In addition, geography, Nevis’ somewhat different economic structure, the fact that there were separate political parties on each island, and the perception that St Kitts had longneglected the interests of Nevis, were factors in increasing secessionist feeling (Griffin, 1998; Midgett, 2004). In 1977, the Nevis Reformation Party (NRP) organised a non-binding vote on secession that gained overwhelming support (Midgett, 2005: 78). However, in the period leading up to St Kitts-Nevis independence in 1983, secession for Nevis was not pursued. One reason was the UK government’s opposition to Nevis following the route taken by Anguilla; rather it favoured St Kitts and Nevis becoming independent as a single state (Midgett, 2004). A second was the replacement in 1980 of the much disliked (at least in Nevis) St Kitts-Nevis Labour Party (SKNLP) government by a coalition involving the St Kitts based People’s Action Movement (PAM) and the NRP. The PAM and NRP worked relatively well together, and the NRP had a key role in shaping the new ‘quasi-federal constitution that was unique in its allocation of powers and institutions’ (Byron, 1999: 271). With the new constitution in place and the PAM/NRP coalition continuing in power, the secessionist issue remained relatively dormant. However, the issue was to return to the fore in the 1990s. There were several reasons for this. First, the relationship between St Kitts and Nevis became more fractious with the Concerned Citizens Movement (CCM) winning power in Nevis in 1993 (and again in 1997) and the SKNLP regaining power in St Kitts in 1995. Thus, the generally good relationship between the two islands under PAM/NRP dissipated. Second, electoral politics in Nevis became more competitive and so to gain advantage the rhetoric against St Kitts was heightened. Third, the Nevis economy grew strongly in the 1990s and so its economic viability improved. Fourth, and perhaps most crucially, there was a strong reaction in Nevis against the creation of a Federal Office on the island and the introduction of new federal legislation affecting its offshore financial sector. Both of these developments, rightly or wrongly, were perceived by the CCM in particular as threatening Nevis’ autonomy and economic development (Byron, 1999; Premdas, 1998b). In June 1996, in response to the two Federal initiatives, the Premier of Nevis Vance Amory invoked Section 113 of the 1983 Constitution which provided for the session of Nevis (Byron, 1999: 275). However, two hurdles had to be overcome before secession could be achieved. First, at least two-thirds of the Nevis House of Assembly had to be in favour, and despite the somewhat equivocal attitude of the NRP (there were sharp divisions in the party about the merits of secession) the motion was passed with sufficient support (Midgett, 2004: 61). Second, a referendum on Nevis’s succession had to be held. When it took place on 10 August 1998 61.7 per cent voted in favour and 38.1 per cent voted against (Byron, 1999: 278). Turnout was a low 58 per cent (Midgett, 2005: 81). Although there was a 5 majority in favour, the required two-thirds majority was not achieved and so the move to secession was lost (Premdas, 1998b: 449). In her analysis of the referendum, Byron (1999: 279) lists several factors that proved decisive including the international community, including CARICOM, not supporting secession and private sector interests in both Nevis and St Kitts highlighting the economic risks. In addition, NRP-held areas tended to be less in favour of change (Midgett, 2005: 78). All these factors are still pertinent today and that is why the debate over secession has remained relatively quiet despite continuing tensions between Nevis and St Kitts. The islands of the Dutch Caribbean The Charter of the Kingdom of the Netherlands, which still largely underpins relations between the Netherlands and its territories, was agreed in 1954 and laid out the arrangements for a federal state, comprising three self-governing autonomous countries of supposedly equal standing: the Netherlands, Suriname and the Netherlands Antilles (consisting of Aruba, Curaçao, Bonaire, Saba, St Eustatius and St Maarten). Despite changes in the membership of the Kingdom (see below), the original provisions of the Charter remain largely in place, in part because any reform requires the consent of all parties. In principle, although not always in practice, the countries of the Kingdom are autonomous in relation to internal matters, while the Kingdom oversees defence, foreign affairs, Dutch nationality, and extradition. The Charter stipulates also areas of communal responsibility, which require the partners to co-operate, for example in the areas of human rights and freedoms, the rule of law and good governance. Ultimately, however, the Charter allows for higher supervision – in essence a tool of last resort – by the Dutch Crown to impose its authority (De Jong, 2005). Aruba exits the Netherlands Antilles When the Charter was signed, it was expected that the Caribbean countries would seek their independence at some time in the future, and as a consequence the Netherlands agreed to give them a significant measure of autonomy. Indeed, by the early 1970s the Netherlands wanted to ‘rid itself of its last colonies in a decolonising world’ (Hoefte and Oostindie, 1991: 74). One consequence was that Suriname gained its independence in 1975. However, the island countries of the Netherlands Antilles were reluctant to follow suit despite strong encouragement from the Dutch government. So it was the metropolis, not the former colonies, pressing for independence (Hoefte and Oostindie, 1991: 93). Nevertheless, Aruba was questioning its position within the Netherlands Antilles and its links with Curaçao. Many Arubans felt Curaçao was damaging their interests with its ‘suffocating tutelage and administrative inefficiency’ (Hoefte and Oostindie 1991: 75). Moreover, racial tensions between mainly Euro-Amerindian Arubans and black Curaçaoans played their part (Oostindie and Klinkers, 2003: 122). A key figure at this time was Betico Croes, leader of the Movimiento Electoral di Pueblo (MEP), who began to lobby The Hague for a change in policy that would provide a new status for the country. Eventually it was agreed that Aruba could attain separate status as a country within the Kingdom, but only if it moved towards independence within a decade (Oostindie and Klinkers, 2003: 126-27). The specific link between status aparte and independence was made so to deter other islands who wanted a separate status but not independence. As Oostindie and Klinkers argued, ‘The Hague nurtured a deep apprehension of an outcome where all six islands would enjoy separate relationships with the Netherlands’ (2003: 127). In 1986, Aruba gained its separate status but then reneged on its promise to move to independence. The Hague acquiesced and thus the country remained part of the Kingdom. Indeed, it has been argued that independence was never the real objective. Rather, ‘[i]t was purely a strategy to dislodge the island from Curaçao’ (Oostindie and Klinkers, 2003: 129). 6 The end of the Netherlands Antilles In the early 1990s a broad political consensus emerged that the Netherlands Antilles and Aruba would be better off remaining part of the Kingdom, primarily owing to their relatively good economic performance, as well as the ready support of the Netherlands. Therefore the temporary nature of the provisions of the Kingdom became permanent, and the Dutch Government in turn felt that a stronger role for the Kingdom was needed to more effectively oversee good governance in the territories. However, there was strong opposition to this from the islands, and no reform was possible (De Jong, 2009: 27). So the Dutch Government employed its financial assistance to the region to effect changes at the local level in areas such as the organisation of the Antillean Government, prison conditions, police operations and criminal investigations (De Jong, 2005: 95). However, this rather piecemeal approach was not a substitute for proper reform. As well as problems in Kingdom relations, the operation of the Netherlands Antilles was questioned. The government structure consisted of two tiers: the national level and the island level, with elections held every four years. However, as the island elections took place during the mid-point of the national government there was little time for stable government and effective policy-making. Furthermore, after Aruba left the Netherlands Antilles, the territory was out of balance and dominated by Curaçao, the largest island by far. Curaçao felt that its interests were not being met because of the demands of the smaller islands, while those islands felt that Curaçao dominated the Antillean Government (De Jong, 2009). As a result of these structural problems, a number of serious difficulties manifested themselves in the Netherlands Antilles, including corruption involving prominent political figures, a substantial public debt, a high murder rate, significant levels of drugs-trafficking, inadequate environmental safeguards, and widespread social dislocation. There was also increasing public concern in the Netherlands about the situation in the Antilles; in part because of allied alarm about the poor level of integration of young Antillean migrants in the Netherlands, caused to an extent by their native language being Papiamento and not Dutch. Faced with such problems, the Dutch Government made several attempts to negotiate with the islands to improve standards of governance, but until recently all efforts had failed. However, in 2004 attitudes changed owing to the worsening levels of violence and drugstrafficking in the Netherlands Antilles that created a growing image of a failed state, and all parties agreed that the Antillean construct should be disbanded and a new set of relationships established (De Jong, 2009). During 2004 and 2005, referendums were held in the islands and all but St Eustatius voted for the dissolution of the Netherlands Antilles, and that was sufficient to bring the Antilles to an end. Full independence was an option on the ballot papers, but there was little support for it. In the Curaçao referendum, for example, only five per cent voted for independence. After a period of initial negotiations it was agreed in October 2006 that Bonaire, St Eustatius, and Saba (BES) would become part of the Netherlands as special-status municipalities, despite objections about the requirement to adopt gay marriage, abortion and euthanasia. This meant that the islands would be overseen by the Netherlands while retaining local government functions, and would become ‘partially integrated jurisdictions’ (Corbin, 2011: 3). Then in November, the two larger territories, Curaçao and St Maarten, signed an agreement with the Dutch Government to become autonomous islands within the Kingdom, a similar status to that of Aruba. However, there was a pact that the Kingdom would oversee the public finances and the rule of law of the two islands. It was also agreed that the public debt of the Netherlands Antilles and of the island governments would be largely forgiven (The Annual Register, 2007: 159; De Jong, 2009). The path towards implementation was not a smooth one, but eventually on 10 October 2010 the Netherlands Antilles was dissolved. 7 Separation not independence So for territories of the Dutch Caribbean separation from each other rather than independence from the Netherlands has been the key concern over the last three decades. The subsequent process of reform has been very protracted and divisive, and the degree of autonomy awarded to each island after the dissolution of the Netherlands Antilles has been strictly limited, despite what many of them originally wanted. However, it is worthwhile to note that, in the end, The Hague acceded to something it had resisted for many years – the islands enjoying separate relationships with the Netherlands. But now, except for some likely tweaking of the new arrangements, further reform is off the agenda unless the idea of independence is resurrected. Brief mention should be made here of the new coalition government in Curaçao as it relates to the independence issue. The second largest party in the coalition Pueblo Soberano (PS) is a pro-independence party and was strongly opposed to Curaçao’s new status, while the junior member Movishon Antia Nobo (MAN) also voted against the adoption of the new constitution. (In the 2010 general election, the PS won 19 per cent of the votes while the MAN received nine per cent.) Subsequently, concerns were raised about the government promoting the idea of independence despite the majority of people being against it. In response, prime minister and leader of the Movementu Futuro Korsou (MFK) Gerrit Schotte stated that Curaçao was not ready for independence and that it would be 10 to 15 years before it was (The Daily Herald, 2010). Puerto Rico and US Virgin Islands The current status of the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico was established in 1952, under Law 600 which stipulates the responsibilities and powers for both the territory and the US. After the USA took control of Puerto Rico following the Spanish-Cuban-American War of 1898 and until 1952, the territory was an unincorporated territory that was ‘foreign to the United States in a domestic sense’ as it was neither a state of the USA nor a sovereign republic (Pantojas-Garcia, 2005: 164). Despite this, Puerto Ricans were granted US citizenship in 1917. Hence, they are US citizens by statute, and can move freely to the USA. Nevertheless, the period up to 1952 witnessed significant opposition to US control, and the independence issue was at its most potent. There were a number of terrorist attacks in both the US and Puerto Rico and wide scale detentions in Puerto Rico (Political Parties of the World, 2009: 636). The Partido Popular Democrático (PPD) favoured independence at this point but with the start of the Cold War swung behind Commonwealth status. The Partido Independentista Puertorriqueño (PIP) was then formed in 1946 to continue the advocacy of independence, but the option became increasingly unpopular amongst the local population. As the Cold War came to an end the question of Puerto Rico’s status re-emerged as a key issue, and two attempts were made via referenda to resolve it in the 1990s. However, none were successful due to a lack of consensus on the way forward. Neither statehood (compete annexation to the US federal system as a state) nor remaining a commonwealth had majority support. Independence was also an option but scored less than five per cent of the vote on each occasion. The electorate shied away from independence for several reasons including the substantial trade benefits and monetary transfers accrued from Puerto Rico’s relationship with the USA, and the reluctance to relinquish their US citizenship as there is significant circular migration between Puerto Rico and the US. Duany calls Puerto Rico ‘the nation on the move’ (2007: 55). Moreover, once in office, neither party gave priority to changing Puerto Rico’s political status (Israel Rivera, 2009: 51). Recently, the status issue has again taken centre stage. One reason is that the territory is in the midst of its worst economic crisis in modern history. The result has been worsening social conditions with high and increasing unemployment, significant poverty, 8 drugs-trafficking and a high murder rate. So there is unease in Puerto Rico that the lack of agreement over the status issue is causing a dangerous degree of stagnation to set in. A second and related reason is that funding caps have been placed on federal programmes, such as health care and housing, due to Puerto Rico’s commonwealth status which puts it as a disadvantage to other parts of the USA. Furthermore, because the US has signed a number of free trade agreements with other competitor jurisdictions in the region (such as Mexico and the Dominican Republic), Puerto Rico has lost its privileged trading position in the US market and its economic competitiveness has been negatively impacted. In addition, because the US Congress has ended the schemes which granted federal tax exemption to US corporations for earnings gained in Puerto Rico, the Territory’s status is now much less important to them (Israel Rivera, 2009: 54). The consequence is that plans are now being put in place for a new vote on Puerto Rico’s status (Caribbean Insight, 2011: 9), and there is a stronger sense than for a while that the status issue can be resolved with statehood being a distinct possibility. Independence will not be chosen. In contrast to Puerto Rico, political status is not an issue in the US Virgin Islands, including St Thomas, St Croix and St John. The lack of a strong distinct national identity, the dominance of the English language, its small size, the limited population (112,000 compared with four million for Puerto Rico) and its narrow productive base (mainly tourism) make it very difficult for the islands to move to either statehood or full independence (Israel Rivera, 2009). Indeed, when a referendum was held in 1993 on the status issue, a large majority (80 per cent) voted for continued or enhanced territorial status with the US. Only five per cent voted for independence (Israel Rivera, 2009: 48). At present the islands are an organized non-incorporated territory, governed by a US Congressional Organic Act, and overseen by the US Office for Insular Affairs. This legal and administrative structure means that the US Virgin Islands has less political and economic autonomy than Puerto Rico. Guadeloupe and Martinique Unlike the British, Dutch and US territories, the French Overseas Departments in the Caribbean are fully part of France, and therefore ‘integrated jurisdictions’ (Corbin, 2011: 3). However, the political and economic considerations facing the Départements d’Outre-Mer (DOM) are similar. The law of assimilation of 19 March 1946 under Article 73 of the French Constitution granted Guadeloupe and Martinique (along with French Guiana and Réunion) the administrative status of Département so that all territorial institutions operate like their metropolitan equivalents in France (Daniel, 2005: 60). In addition, laws and regulations enacted in Paris apply automatically to the DOM. A Préfet nominated by Paris represents the state and has responsibility for foreign relations, defence, law and order and the provision of the national service. A Conseil Général manages the Département. Also, locally elected deputies and senators represent each DOM in the French parliament. With this system, and as far as Paris was concerned, ‘… the question of their constitutional status was closed’ (Bishop, 2008: 67). Greater autonomy versus independence Assimilation, however, came under attack particularly from left-wing groups in the 1960s and 1970s. Led by Aimé Césaire who had been a strong supporter of départementalisation and his Parti Populaire Martiniquais (PPM), there were demands for greater local autonomy. It was argued that départementalisation was merely perpetuating old colonial structures and leading to economic stagnation. Others on the left went further and called for independence and several groups were formed to push for this change (Oostindie and Klinkers, 2003; Miles, 2001). Guadeloupe witnessed the most militant pro-independence action with violence occurring periodically in the 1970s and early 1980s. Paris was also the 9 focus of Caribbean independentist terrorism (Miles, 2001: 50-51). The greater militancy on the part of some Guadeloupeans at this time and indeed later has much to do with the less radical and nationalist brand of party politics in the département which means voices of opposition often find alternative (and more aggressive) avenues of protest (Bishop, 2008: 140-143). Nevertheless, it remained the case that a majority of citizens in both Guadeloupe and Martinique wanted to retain their link with France. The support for continued départementalisation was strengthened with a commensurate weakening in the independence forces when in 1982 French President François Mitterand introduced greater decentralisation into the system by creating a new level of government – the Région – with a directly elected body, the Conseil Régional, whose main role was to promote social, economic, cultural and scientific development of the Région (Mrgudovic, 2005: 73). In principle, each region was to cover a few départements. For geographical and political reasons it was impossible to incorporate the four DOM within a single region. Thus four overseas regions were established; one for each DOM. Martinique, Guadeloupe, French Guiana and Réunion became then a Département and a Région. The Région operated on the same geographical territory, same population and same electorate as the Département (Mrgudovic, 2005: 73-74). Although the reform caused significant problems for the DOM in terms of overlapping activities, increased administrative costs and local political rivalry it awarded Guadeloupe and Martinique an important ‘cultural right to difference’ which helped to neutralise ‘all but the most hardline of oppositionist parties’ (Miles, 2001: 50). The limits to reform Aware of the bureaucratic tensions in the DOM, Prime Minister Lionel Jospin and his socialist government established a new programme for the territories in 2000 entitled (Loi d’Orientation pour l’Outre-Mer or LOOM). This gave members of the Conseil Général and Conseil Régional in each DOM an opportunity to discuss and submit to the Prime Minister any proposal regarding an evolution of their status, including a move towards independence (Mrgudovic, 2005: 75). However, the changes suggested were rather moderate, and focused on administrative reform. Notwithstanding, with the defeat of the Socialists in the 2002 French parliamentary elections, the LOOM process was halted and the Conservatives introduced a new decentralisation reform. Again, the reforms requested by the elected representatives of Martinique and Guadeloupe were limited; the most radical being the reunification of the Conseil Général and the Conseil Régional within a single elected assembly. The results of voting held in December 2003 were unexpected as the change was rejected in both territories (Daniel, 2009: 75). Voters were concerned that, if any change was made, their social and economic advantages emanating from the French state might be threatened. While the administrative structures of Guadeloupe and Martinique remained unchanged, Saint-Barthélemy and Saint-Martin, two islands administratively attached to Guadeloupe, used their right under the decentralisation reform to revise their status. Both islands expressed a wish to escape Guadeloupe’s management and become two distinct territories ruled by Article 74 of the French Constitution. During the local referendums that took place, both electorates voted clearly in favour of this new status that would allow them legislative speciality, more local power and a more direct link with Paris (Mrgudovic, 2005: 80; Corbin, 2011: 3). They are now known as French overseas collectivities (Collectivités d’Outre-Mer or COM). The political and legal assimilation of the DOM has taken place along with enormous injections of money from mainland France and increasingly from the European Union (EU), which has produced high levels of development. Financial transfers from Paris and Brussels 10 are spent on social security, health care, education, tax breaks, and public employment. It is interesting to note ‘…that the most anti-European, autonomist left-wing elements of the Antillean political elite are the very same people who have … wielded terrific sums of EU money and legitimised the decentralised French state by their participation in its machinations’ (Bishop, 2008: 127). In other words, even though some of the rhetoric might be against France and the EU, Antillean politicians realise that gaining funds and managing them effectively are key to their electoral success. However, because they are in reality so closely aligned with the status quo, these Antillean politicians are unable to properly address concerns about an economic model that does not allow the DOM to achieve self-sustained development despite good rates of growth. Indeed, growth is paradoxically derived from a considerable decline in the productive capacities of the territories (Bishop, 2008: 125). Thus, the significant monetary transfers provided have actually impeded economic development. Some of these structural problems, exacerbated by the effects of the global financial crisis, were the cause of widespread protests in the DOM during the early part of 2009. Workers demanded action over low wages (in comparison with mainland France rather than the rest of the Caribbean) and the high cost of living, which is, in part, caused by the high level of imports from France (Caribbean Insight, 2009: 6). Agreement was reached on a number of issues, but the protests re-opened the debate about the DOM’s relationship with France. In Martinique it was agreed that a referendum should be held on whether the département should have greater autonomy and become an autonomous territory governed by Article 74 (rather than Article 73) of the French Constitution. The vote took place in January 2010 and against expectations almost 80 per cent of voters said no. In a follow-up vote two weeks later, voters agreed to the less significant reform of merging the Conseil régional and Conseil général into a single body. The French government accepted the results of both votes and suggested that this now concluded the debate over Martinique’s constitutional relationship with France. In Guadeloupe, meanwhile, it was decided that a referendum was not appropriate. Rather, it was felt that a period of reflection and consensus-building was needed after the violent protests and civil unrest. This was reinforced in the elections for the Conseil régional in March 2010. Victorin Lurel’s left-wing coalition retained power with an increased share of the vote, while two parties led by key figures who organised the labour unrest, gained only three per cent between them. Thus, at the time of writing (May 2011) in Guadeloupe and Martinique there is little appetite for independence and even the quest for greater autonomy is rather muted. Conclusion Across the island territories considered in this paper, any impetus there has been in relation to gaining independence has been diminishing for some time. Driven by local competitive party systems and/or charismatic political leaders Aruba, Bermuda, Montserrat, TCI and particularly Nevis have come closest to achieving independence. But, despite the continued enthusiasm of some of their politicians, the people have shown little appetite for re-visiting the issue. The key factor is that most citizens feel that the existing systems of governance are still better than independence despite the tensions that come to the fore from time to time. This is certainly true for those islands that remain under European or US control. In many respects, the territories have a privileged position in the international system. Their citizens have a final guarantee against autocracy and economic collapse; many territories receive sizeable monetary assistance that has helped them in creating relatively high levels of development; and nationals possess the citizenship of their metropolitan powers. In the case of the British, Dutch and French territories, they also have the freedom of movement across 11 the EU. Even for Nevis the implications of independence from St Kitts are substantial and therefore secessionist feeling is perhaps more rhetorical than actual. Nevertheless, even though independence is not on the agenda, constitutional change certainly is. Indeed, the last several decades have seen a continual process of reform and revision to improve the links that bind the islands to their sovereign centres. However, even here there is caution in starting a process which could then lead to independence or at least less protections and preferences from the metropole. Perhaps the most notable development has been the attempt by some of the islands particularly those formerly part of the Netherlands Antilles and France to break-away from their neighbours and establish more direct links with their metropolitan power. Thus inter-island antipathy and rivalry, and insular particularism, seem to be the primary motivators for change. References The Annual Register (2007) The 2007 Annual Register: World Events. Key events and developments from 2006 (Oxford: ProQuest). Bermuda Department of Statistics (2009) Facts and Figures 2009. Available at www.gov.bm/portal/server.pt/gateway/PTARGS_0_2_980_227_1014_43/http%3B/ptpublis her.gov.bm%3B7087/publishedcontent/publish/cabinet_office/statistics/dept___statistics___ additonal_files/articles/facts_and_figures_2009_0.pdf (accessed 31 March 2010). Bermuda Independence Commission (2005) Report of the Bermuda Independence Commission 1995. Available at www.bermudaindependencecommission.bm/portal/server.pt/gateway/PTARGS_0_2_3191_ 341_1824_43/http%3B/ptpublisher.gov.bm%3B7087/publishedcontent/publish/bic/dept___b ic___reports_docs/articles/report_on_the_bermuda_independence_commission__august_200 5_4.pdf (accessed 3 January 2011). Bishop, M. (2008) Dependency and Development in the Eastern Caribbean: A Comparison of the Political Economies of two Anglophone Micro-States, and two French Départements d’Outre-Mer, PhD Thesis (Department of Politics: University of Sheffield). Byron, J. (1999) Microstates in a Macro-World: Federalism, Governance and Viability in the Eastern Caribbean, Social and Economic Studies, 48, 4, 251-286. Caribbean Insight (2009) French Caribbean, 32, 9, 2 March (London: Caribbean Council). Caribbean Insight (2010a) Montserrat, 33, 4, 25 January (London: Caribbean Council). Caribbean Insight (2010b) Turks and Caicos, 33, 6, 8 February (London: Caribbean Council). Caribbean Insight (2011) Puerto Rico, 34 12, 4 April (London: Caribbean Council). Caribbean Net News (2006) Independence ‘ultimate goal’ for Turks and Caicos, says Chief Minister. Available at www.caribbeannetnews.com (accessed 28 July 2007). Cichon, D. (1989) British Dependencies: The Cayman Islands and the Turks and Caicos Islands, in S. Meditz and D. Hanratty (Eds) Islands of the Commonwealth Caribbean: a regional study, pp. 561-583 (Washington: Library of Congress). 12 Connell, J. (1997) Bermuda: Aberrant or Exemplary Case?, The Round Table, 341, 37-50. Corbin, C. (2011) Self Governance Deficits in Caribbean Dependency and Autonomous Models, Overseas Territories Report, X, 2, March 2011. Available at www.normangirvan.info/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/otr-march-2011.pdf (accessed 14 April 2011). Daniel, J. (2005) The French Departements dóutre mer. Guadeloupe and Martinique, in L. De Jong and D. Kruijt (Eds) Extended Statehood in the Caribbean: Paradoxes of quasi colonialism, local autonomy and extended statehood in the USA, French, Dutch and British Caribbean, pp. 59-84 (Amsterdam, Rozenberg Publishers). Davies, E. (1995) The Legal Status of British Dependent Territories: The West Indies and North Atlantic Region (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press). De Jong, L. (2005) The Kingdom of the Netherlands. A not so perfect union with the Netherlands Antilles and Aruba, in L. De Jong and D. Kruijt (Eds) Extended Statehood in the Caribbean: Paradoxes of quasi colonialism, local autonomy and extended statehood in the USA, French, Dutch and British Caribbean, pp. 85-123 (Amsterdam, Rozenberg Publishers). De Jong, L. (2009) The Implosion of the Netherlands Antilles, in P. Clegg and E. PantojasGarcia (Eds) Governance in the Non-Independent Caribbean: Challenges and Opportunities in the Twenty-First Century, pp. 24-44 (Jamaica: Ian Randle Publishers). Department for International Development (1999) An Evaluation of HMG’s Response to the Montserrat Volcanic Emergency, Volume 1, EV635, December (London: The Stationary Office). Duany, J. (2007) Nation and Migration: Rethinking Puerto Rican Identity in a Transnational Context, in F. Negrón-Muntaner (Ed.) None of the Above: Puerto Ricans in the Global Era, pp. 51-63 (New York: Palgrave Macmillan). Fergus, H. (1989) The Montserrat Independence Issue: Will Conservatism Continue to Prevail?, Caribbean Affairs, 2, 2, 143-151. Fergus, H. (1990) Constitutional Downgrading for Montserrat – Tampering with the Constitution?, Caribbean Affairs, 3, 2, 56-67. Foreign Affairs Committee (2004) ‘Overseas Territories: Written Evidence’, HC 114, House of Commons, March (London: The Stationary Office). Griffin, C. (1998) The Quest for Secession in Nevis: Just Another Political Game?, Journal of Eastern Caribbean Studies, 23, 1, 75-89. Hoefte, R. and Oostindie, G. (1991) The Netherlands and the Dutch Caribbean: Dilemmas of Decolonisation, in P. Sutton (Ed.) Europe and the Caribbean, pp. 71-98 (London: Macmillan). 13 Jane’s (2009) Bermuda Sentinel Country Risk Assessment 2010. Available at www.janes.com (accessed 3 January 2011). Israel Rivera, A. (2009) US Non-Incorporated Territories in the Caribbean: Factors Contributing to Stalemate and Potential Political Change in Puerto Rico and the US Virgin Islands, in P. Clegg and E. Pantojas-Garcia (Eds) Governance in the Non-Independent Caribbean: Challenges and Opportunities in the Twenty-First Century, pp. 45-60 (Jamaica: Ian Randle Publishers). Midgett, D. (2004) Pepper and Bones: The Secessionist Impulse in Nevis, New West Indian Guide, 78, 1 and 2, 43-71. Midgett, D. (2005) The Nevis Secession Vote: The Search for Explanations, Journal of Eastern Caribbean Studies, 30, 4, 77-85. Miles, W. (2001) Fifty Years of Assimilation: Assessing France’s Experience of Caribbean Decolonisation through Administrative Reform, in A. Gamaliel Ramos and A. Israel Rivera (Eds) Islands at the Crossroads: Politics in the Non-Independent Caribbean, pp. 45-60, (Jamaica: Ian Randle Publishers). Mrgudovic, N. (2005) The French Overseas Territories in Change, in: D. Killingray and D. Taylor (Eds) The United Kingdom Overseas Territories: Past, Present and Future, pp. 65-86 (London, Institute of Commonwealth Studies). Oostindie, G. and Klinkers, I. (2003) Decolonising the Caribbean: Dutch Policies in a Comparative Perspective (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press). Pantojas-Garcia, E. (2005) The Puerto Rican Paradox: Colonialism Revisited, Latin American Research Review, 40, 3, 163-176. Political Parties of the World (2009) (London: John Harper Publishing). Premdas, R. (1998) Identity, Ethnicity and Culture in the Caribbean (Trinidad and Tobago: University of the West Indies). Report of the Commissioner Mr Louis Blom-Cooper QC. (1986) Allegations of Arson of a Public Building, Corruption and Related Matters, December (London: HMSO). The Daily Herald (2010) Editorial – Reassurance, 28 September. Available at www.thedailyherald.com/editorial/32-editorial/8697-editorial-reassurance.html (accessed 3 January 2011). Thorndike, T. (1987) When small is not beautiful: the case of the Turks and Caicos Islands, Corruption and Reform, 2, 3, 259-265. Turks and Caicos Islands Commission of Inquiry 2008-2009, Report of the Commissioner The Right Honourable Sir Robin Auld. Available at http://www.fco.gov.uk/en/newsroom/latest-news/?view=News&id=20700728 (accessed 9 September 2009). 14