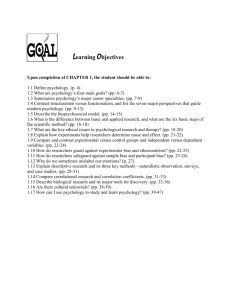

Questions to be Answered in this Section

advertisement