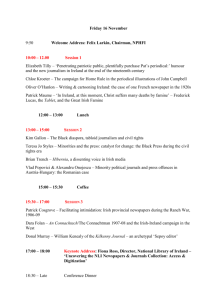

*Ireland from St

advertisement