Annex III RAPEX Injury Severity Table

advertisement

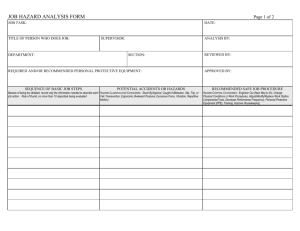

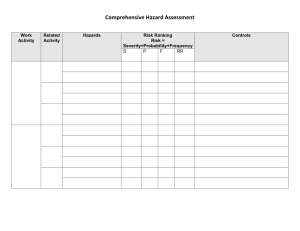

PARTICIPANT INSTRUCTIONS FOR CASE STUDIES Workshop on product risk assessment 20 April 2012, Tel-Aviv, Israel Attached are participant instructions on the case studies, to be discussed at the OECD workshop on product risk assessment, on 20 April 2012, in Tel-Aviv, Israel. Participants are invited to review them and carry out their own risk assessments prior to the workshop. The information would then be shared and discussed at the workshop. Contact: Ewelina Marek; Tel: +(33-1) 45 24 13 68; E-mail: ewelina.marek@oecd.org Peter Avery; Tel: +33 1 45 24 93 63; E-mail: peter.avery@oecd.org N.B. This document and any map included herein are without prejudice to the status of or sovereignty over any territory, to the delimitation of international frontiers and boundaries and to the name of any territory, city or area. DSTI/CP/CPS(2012)3/ADD PARTICIPANT INSTRUCTIONS FOR CASE STUDIES 1. Thank you for participating in the OECD Consumer Product Risk Assessment Workshop. 2. The workshop will provide participants who are actively involved in risk assessment with an opportunity to critically evaluate their own risk assessment practices in the light of practices used by other consumer product regulators and those used in other areas. 3. The workshop includes small group work which will focus on how the risk of certain hazards might be assessed. This is intended to be a very practical ‘hands on’ approach. It would be helpful for participants to review the two case studies (ethanol burners and sky lanterns) and carry out their own risk assessments prior to the workshop, using the Australian and European (RAPEX) approaches. We would then share and discuss the results at the workshop. 4. Instructions for carrying out the assessments are summarised below. Task 1 (using the Australian approach) Please read the Ethanol Burner case study on page 4 of this document. Follow the steps Australia would use to undertake this risk assessment, as outlined in Annex I of this document. Record your responses to each of the steps on the Risk Assessment form contained in Annex II. In undertaking this assessment you will need to refer to the RAPEX injury severity table, contained in Annex III of this document. Please note that the risk assessment form will automatically generate a risk assessment rating based on the responses you have entered, if you clicked on ‘enable macros’ when you opened the document you are reading now. If the form does not appear to work please email ruth.mackay@accc.gov.au – we are able to provide you with a manual version. Identify any tables or tools you would use in your own organisation to help undertake such an assessment. Identify any additional steps you would undertake to in the assessment. 5. Please bring your completed risk assessment on this scenario to the workshop in Israel. If possible, please send an electronic version to the OECD secretariat (ewelina.marek@oecd.org), in advance of the meeting. Task 2 (using the EU RAPEX approach) Please read the sky lantern case study on page 6 of this document. 2 DSTI/CP/CPS(2012)3/ADD Follow the steps the European Commission would use to undertake this risk assessment, as outlined in Annex IV of this document. Please note that for this exercise you will need the EU RAPEX Risk Assessment Guidelines along with its tables. These are available in the document at: http://ec.europa.eu/consumers/safety/rapex/docs/rapex_guid_26012010_en.pdf The presentation of the guidelines begins on page L 22/33. It is also possible to carry out an analysis via an on-line tool, which is available at: http://europa.eu/sanco/rag/public/index.cfm?event=home&CFID=1734987&CFTO KEN=2f22fb417085e209-859FBF87-D3B3-DB9440F068D85D241C13&jsessionid=2202237f1edd3c302697TR. Identify any tables or tools you would use in your own organisation to help undertake such an assessment. Identify any additional steps you would undertake in the assessment. 6. Please bring your completed risk assessment to the workshop in Israel. If possible please send an electronic version to the OECD secretariat (ewelina.marek@oecd.org), in advance of the meeting. 3 DSTI/CP/CPS(2012)3/ADD CASE STUDY ON LIQUID ETHANOL BURNERS FOR MOOD LIGHTING 7. Mood lighting products that burn liquid ethanol fuel have become increasingly popular over recent years. There are portable versions for indoor or outdoor domestic use on a table or bench-top. Some products are built into furniture such as coffee tables. Examples of the product are shown below. Source: http://www.recalls.gov.au/content/index.phtml/itemId/1010543 http://www.recalls.gov.au/content/index.phtml/itemId/1007032 , 4 April 2012 Source : http://www.recalls.gov.au/content/index.phtml/itemId/999479 , 4 April 2012 4 DSTI/CP/CPS(2012)3/ADD 8. Originally available in specialist heater and barbeque retail stores, these products are also now being sold in some major department and grocery stores. 9. These products burn with a blue flame that is often poorly visible under high levels of background lighting. Some marketing images may make the flame appear redder and more visible than is often the case. 10. There have been incidents in which a consumer, because of the invisible flame, has attempted to refuel or light the device while it is still burning. This has in some cases caused the flame to ‘flash’ or for the fuel to ‘spatter’, sometimes giving the impression of an explosion. 11. Some reported injuries include: A man received burns to fifty per cent of his body and was admitted to intensive care after attempting to ignite an already lit device. A man narrowly avoided burns but caused a fire and significant property damage to his house when attempting to light an ignited ethanol burner. A woman received minor burns to both of her hands and also caused significant damage to her house and property when attempting to light an ethanol burner. 12. The manuals for these devices sometimes provide unclear safety instructions for lighting the flame. Products often have no warning labels. However, the German standard DIN 4734-1:2011 requires product to be labelled “Filling in operation and in the warm state is not allowed”. 5 DSTI/CP/CPS(2012)3/ADD CASE STUDY ON SKY LANTERNS 13. Sky lanterns are hot-air balloons made of a paper outer shell with a solid flammable material fixed at the lower opening. Sizes of 75 up to 100 cm are not unusual. Once the burning material is ignited, a sky lantern can reach flying heights of up to 500 metres and can move, during its approximate 20 minutes flight, several kilometres away from its starting place. In the ideal case, the flame extinguishes after the burning material has been used up, and the sky lantern sinks to the ground. Source: http://www.muensterschezeitung.de/nachrichten/nrw/art1544,597332. 7 July 2009 Source: http://wiesbaden.eins.de/articles/757312-lokales-das-wars-mit-den-party-himmelslaternen. 6 August 2009 14. There were a number of incidents reported which resulted in up to EUR 230 000 (USD 300 000) in harm and damage. Where the use of sky lanterns is prohibited, penalties of up to EUR 38 000 (USD 50 000) can be imposed. In cases when its use is permitted, detailed user instructions and warnings must be provided with the lantern. 15. The use of sky lanterns may cause the following hazards: Fire could be caused by a sky lantern landing on flammable ground before the flame is completely extinguished, 6 DSTI/CP/CPS(2012)3/ADD Fire could occur due to collision of a flying sky lantern with buildings, trees or other objects, A flying sky lantern could catch on fire (e.g., due to wind) – burning parts could fall on flammable material, A sky lantern could catch fire when started, posing a risk for the person igniting the lantern and for bystanders, A landing sky lanterns could cause a distraction/nuisance to car drivers, A sky lantern could collide with aircraft, causing a nuisance to pilots, Metal parts of sky lanterns (e.g. the frame) could be eaten by cattle – resulting in internal injuries, Fallen lanterns could cause environmental pollution. 7 DSTI/CP/CPS(2012)3/ADD ANNEX I ACCC PRODUCT SAFETY NOMOGRAPH INSTRUCTIONS 8 DSTI/CP/CPS(2012)3/ADD 1. Define scope of risk assessment 2. Assess severity of injury Hazard Assessment Estimate probability of hazard occurring Select one of the six defined probability levels between ‘Remote’ and ‘Almost inevitable’ for the hazard, injury and population specified for the assessment. Enter the selected level in the nomograph tool, including a short explanatory statement. This estimate is based on the premise that the consumer is in possession of the product. In practice, the data necessary to support this estimate is sometimes weak and the result is at times subject to uncertainty. Factors to consider in the estimate include: Is every unit delivered inherently unsafe or does the hazard occur in only a subset of products? Does the hazard occur with almost every use or in only rare circumstances? Does the hazard occur with new product or only after use and/or ageing? Is the product used frequently (e.g. daily) or rarely (e.g. annually)? What is known about the rate of failure or injuries? 4. Determine potential for hazard recognition Assess severity of injury Select an EU RAPEX injury severity level between 1 and 4 based on the tables in Annex III. Enter the selected level in the nomograph tool (Annex II), including a short explanatory statement. For types of injury not explicitly addressed in the tables, use the general RAPEX injury criteria also defined in Annex III. The severity level should be based on the estimated maximum potential injury for the specified population, but neglecting extremely unlikely injury scenarios that are not supported by injury data. 3. Estimate probability of hazard occurring Define scope of assessment The first step is to clearly specify the hazard and the affected population. Depending on the nature of the assessment, the assessor may choose to perform multiple assessments for multiple hazards or population groups with different capacities to tolerate injury, to recognise and avoid hazards and with different access to the product in question. The assessor may choose to complete separate assessments for infants, children, elderly, general consumers or other groups. However, this will often not be necessary for many product safety problems in which the affected population is determined by the nature of the product and the hazard under assessment. Estimate the potential for hazard recognition Select one of the five defined recognition levels between ‘Highly improbable’ and ‘Almost inevitable’ for the hazard, injury and population specified for the assessment. Enter the selected level in the nomograph tool, including a short explanatory statement. The assessor should estimate the ability of an average consumer within the defined population to recognise and avoid the hazard. The assessor should consider whether warnings on the product increase the hazard recognition. For vulnerable groups such as children, the estimate should also consider the extent to which responsible carers such as parents can realistically act to recognise and avoid the hazard on behalf of the vulnerable group. 5. Hazard (initial risk assessment) The nomograph multiplies the selected severity, probability and recognition estimates to generate an initial risk assessment of the hazard with one of ten values between ‘Virtually non-existent’ and ‘Extremely High’. 9 DSTI/CP/CPS(2012)3/ADD 6. Adjust for availability of product 7. Risk Assessment Estimate availability Select one of the four levels defined for the availability of the product and enter this in the nomograph tool, including a short explanatory statement: ‘Rare’ – scarcely available; not normally made or imported in this jurisdiction ‘Limited’ – distributed in small quantity or only in a small region ‘General’ – distributed and readily available across the jurisdiction ‘Widespread’ – distributed across the jurisdiction and in use in almost all households. Risk (final risk assessment) The nomograph modifies the initial risk assessment (hazard) with the selected availability estimate to generate a final risk assessment with one of ten values between ‘Virtually non-existent’ and ‘Extremely High’. Based on experience, a final risk assessment below ‘Moderate’ may be considered for no further action. However, a final risk assessment of ‘Moderate’ or higher may be considered for more detailed assessment or intervention of some kind. Acknowledgement 16. The ACCC Product Safety Nomograph is based on the model originally developed for the New Zealand Ministry of Consumer Affairs by H.G. Benis in 1990. The original tool was graphical and paper-based as illustrated below. 17. Subsequent usage by Australian product safety regulators such as the ACCC has influenced these Instructions for Use. Most recently, the ACCC has updated the model by adopting the recent EU RAPEX injury severity levels, which were also influenced by the Benis model. The ACCC has incorporated the nomograph in a macro within a Microsoft Word document (Annex II). 10 DSTI/CP/CPS(2012)3/ADD 11 DSTI/CP/CPS(2012)3/ADD ACCC Product Safety Nomograph Tool 1. Scope of assessment Which hazard and for which population is this assessment: 2. Maximum potential injury Select one: Explain why you chose this rating: 3. Probability of hazard occurring Select one: Explain why you chose this rating: 4. Hazard recognition Select one: Explain why you chose this rating: 5. Hazard (Initial risk assessment) [Based on sections 2 to 4] Moderate (54) 12 DSTI/CP/CPS(2012)3/ADD 6. Availability Select one: Explain why you chose this rating: 7. Risk (Final risk assessment) [Based on sections 2 to 5] Extremely Low (24) 13 DSTI/CP/CPS(2012)3/ADD ANNEX III RAPEX INJURY SEVERITY TABLE 14 DSTI/CP/CPS(2012)3/ADD 15 DSTI/CP/CPS(2012)3/ADD 16 DSTI/CP/CPS(2012)3/ADD 17 DSTI/CP/CPS(2012)3/ADD ANNEX IV EUROPEAN RAPEX RISK ASSESSMENT STEPS 1. Describe the product and its hazard. 2. When you describe the injury scenario, consider the frequency and duration of use, hazard recognition by the consumer, whether the consumer is vulnerable (in particular children), protective equipment, the consumer’s behaviour in the case of an accident, the consumer’s cultural background, and other factors that you consider important for the risk assessment. See section 3.3 in attachment 1 and table 2 in attachment 2 of RAPEX Guidelines. Determine the level of severity (1 to 4) of the injury to the consumer. If the consumer suffers from several injuries in your injury scenario, estimate the severity of all those injuries together. See table 3 in attachment 2 for guidance of RAPEX Guidelines. Assign a probability to each step of your injury scenario. Multiply the probabilities to calculate the overall probability of your injury scenario. See left-hand side of table 4 in attachment 2 for guidance of RAPEX Guidelines. Determine the risk level. 7. Describe the steps to the injury (ies) clearly and concisely, without exaggerating the details (‘shortest path to injury’, ‘critical path to injury’). If there are several concurrent injuries in your scenario, include them all in that same scenario. Determine the probability of the injury scenario. 6. Start with the intended user and the intended use of the product for your first injury scenario. Take other consumers (See table 1 in attachment 1 of RAPEX Guidelines) and uses for further scenarios. Determine the severity of the injury. 5. Identify the standard(s) or legislation applicable to the product. Describe an injury scenario in which the product hazard(s) you have selected causes an injury(ies) or adverse health effect(s) to the consumer you selected. 4. Is there only one hazard within the product? Are there several hazards? See table 2 of RAPEX Guidelines. Identify the type of consumer you want to include in your injury scenario with the hazardous product. 3. Describe the product unambiguously; does the hazard concern the entire product or only a (separable) part of the product? Combine the severity of the injury and the overall probability of the injury scenario and check the risk level in table 4 in attachment 2 of RAPEX Guidelines. Check whether the risk level is plausible. 18 DSTI/CP/CPS(2012)3/ADD 8. If the risk level does not seem plausible, or if you are uncertain about the severity of injury(ies) or about the probability(ies), move them one level up and down and recalculate the risk. This ‘sensitivity analysis’ will show you whether the risk changes when your input changes. If the risk level remains the same, you can be quite confident of your risk assessment. If it changes easily, you may want to err on the safe side and take the higher risk level as ‘the risk’ of the consumer product. You could also discuss the plausibility of the risk level with experienced colleagues. Develop several injury scenarios to identify the highest risk of the product. If your first injury scenario identifies a risk level below the highest risk level set out in these guidelines, and if you think that the product may pose a higher risk than the one identified, Please take into account that the highest risk normally refers to a risk of a product that allows for application of the most effective risk management measures. In specific cases, a particular hazard may lead to a less-than-highest risk and require specific risk management measures. As a rule of thumb, injury scenarios may lead to the highest risk level set out in these guidelines where: 9. Select other consumers (including vulnerable consumers, such as children), Identify other uses (including reasonably foreseeable uses), in order to determine which injury scenario puts the product at its highest risk. The injury(ies) considered are at least at levels 3 or 4, The overall probability of an injury scenario is at least greater than 1/100. See table 4 in attachment 4 for guidance of RAPEX Guidelines. Document and pass on your risk assessment. Be transparent and also set out all the uncertainties that you encountered when making your risk assessment. Examples for reporting risk assessments are provided in section 6 of attachment 1 of RAPEX Guidelines. 19