Forest Ecology Unit - WUP Center - Michigan Technological University

advertisement

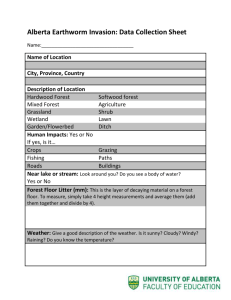

Forest Ecology Unit: Investigating What Makes a Healthy Forest By Cindy Ruotsi Target Grade/Subject: 10th Grade Biology Table of Contents – Forest Ecology Lesson Plan – Summer 2010 Background Information ............................................................................................................................................... 3 Unit Overview ........................................................................................................................................................... 3 References ................................................................................................................................................................ 3 Teaching and Learning Objectives ............................................................................................................................ 4 Content Expectations Addressed.............................................................................................................................. 4 Materials ................................................................................................................................................................... 5 Classroom and Field Activities ...................................................................................................................................... 6 Lesson 1 – Healthy Forests ....................................................................................................................................... 6 Teacher Preparation ............................................................................................................................................. 6 Opening Activity.................................................................................................................................................... 6 Discussion ............................................................................................................................................................. 6 Homework ............................................................................................................................................................ 6 Student Handout 1: Lesson 1 - Play ...................................................................................................................... 8 Student Handout 2: Lesson 1 – “A healthy forest gives us…” ............................................................................ 12 Lesson 2 – How Can We Monitor Forest Health ..................................................................................................... 14 Teacher Preparation ........................................................................................................................................... 14 Opening Activity.................................................................................................................................................. 14 Small Group Discussions ..................................................................................................................................... 14 PowerPoint – Healthy or Not? ............................................................................................................................ 14 Discussion of PowerPoint ................................................................................................................................... 14 A Closer Look at the Pictures .............................................................................................................................. 14 Homework .......................................................................................................................................................... 15 Student Handout 1: Lesson 2 – Thinking About It .............................................................................................. 16 Student Handout 2: Lesson 2 – Earthworm Reading .......................................................................................... 17 Lesson 3 – Monitoring Forest Health – Earthworm Sampling ................................................................................ 19 Background Information ..................................................................................................................................... 19 Teacher Preparation ........................................................................................................................................... 19 Opening Discussion ............................................................................................................................................. 19 Introduction to Techniques and Pre-Lab Write Up............................................................................................. 20 Field Trip ............................................................................................................................................................. 20 Follow Up – Post Field Trip ................................................................................................................................. 20 Possible Extensions ............................................................................................................................................. 20 Student Handout 1: Lesson 3 – Mustard Extraction Method ............................................................................. 21 Student Handout 2: Lesson 3 – Hand Sampling Method ................................................................................ 22 Lesson 4 – Monitoring Forest Health – Biodiversity Study ..................................................................................... 23 Teacher Preparation ........................................................................................................................................... 23 Opening Activity.................................................................................................................................................. 23 Introduction to Field Trip and Pre-Lab Write up ................................................................................................ 23 Field Trip ............................................................................................................................................................. 23 Follow Up – Post Field Trip ................................................................................................................................. 24 Homework .......................................................................................................................................................... 24 Student Handout 1: Lesson 4 – Tree ID .............................................................................................................. 25 Student Handout 2: Lesson 4 – Field Trip Handout ............................................................................................ 27 Lesson 5– Monitoring Forest Health – Salamander Study ..................................................................................... 28 Teacher Preparation ........................................................................................................................................... 28 Teacher Background Information and Instructions ............................................................................................ 28 Opening Activity.................................................................................................................................................. 30 Introduction to Field Trip .................................................................................................................................... 30 In Class and Homework ...................................................................................................................................... 31 Field Trip ............................................................................................................................................................. 31 Follow Up – Post Field Trip ................................................................................................................................. 31 Evaluation ................................................................................................................................................................... 32 Rubrics .................................................................................................................................................................... 32 Science Journal Rubric ........................................................................................................................................ 32 Science Lab Report Rubric .................................................................................................................................. 33 Background Information Unit Overview The following unit works well in a Biology classroom during an Ecology unit. It offers many opportunities for science inquiry, and allows students to recognize the social implications of many science-related issues. During this five lesson unit, students will investigate what it means for a forest to be healthy, will learn how to measure whether or not a forest is healthy, and will become stewards of a local forest. References The following sources were consulted, and adapted for use in my classroom: Corsentino, Pattyanne. "The Blind Men and the Ecosystem." Ecosystem Matters (1995): 147-153. Web. 10 Aug 2010.<http://fs.usda.gov/Internet/FSE_DOCUMENTS/stelprdb5073114.pdf>. I used the above resource to create a play for my students to perform. The play that I adapted from this one is found in Lesson 1. Hale, Cindy. "Invasive Earthworms?" Great Lakes Worm Watch. University of Minnesota Duluth, 1999. Web. 16 Aug 2010. < http://www.nrri.umn.edu/worms/>. The above resource was used in Lesson 4. I adapted the sampling methods for use in my classroom. There are also links within the site for keys to help identify worm species. Harless, Meagan. "Terrestrial Salamander Monitoring." Forest Resources and Environmental Science Teacher Institute. Houghton, MI, Michigan Technological University, Department of Biological Sciences. 2010. 1-11. Print. Harless, Meagan. "Terrestrial Salamanders of Michigan." Forest Resources and Environmental Science Teacher Institute. Houghton, MI, Michigan Technological University, Department of Biological Sciences. 2010. 1. Print. The two resources above, provided by Meagan Harless, are used in Lesson 5. Koch, Rita. "Glossary of Terms Used in this Tree ID." Forest Resources and Environmental Science Teacher Institute. Houghton, MI, Michigan Technological University, School of Forest Resources and Environmental Science. 2010. 1 - 2. Print. The tree ID key is used in Lesson 4 to help students identify leaves and tree species to measure the biodiversity of a local forest. 2010 Michigan Fishing Guide. Michigan Department of Natural Resources and Environment, 2010. Web. 23 Aug 2010. <http://www.michigan.gov/documents/dnr/full-no-ads_272056_7.pdf>. The above website was used in Lesson 3. Minnesota Department of Natural Resources. 2010. The Minnesota Department of Natural Resources Web Site (online). Accessed 2010-8-16 at http://www.dnr.minnesota.gov/sitetools/copyright.html This resource was used for a reading that my students will do during Lesson 2. I also used several pictures from this website in the PowerPoint Presentation – “Healthy or Not.” Ottawa National Forest - Resource Management!. United States Forest Service, 2007. Web. 23 Aug 2010. <http://www.fs.usda.gov/Internet/FSE_DOCUMENTS/stelprdb5150394.ppt >. I took several pictures for the PowerPoint – “Healthy or Not” from this website. There is a link to a PowerPoint presentation, called “Invasive Plants of the Upper Peninsula Slide Show.” Stoyenoff, Jennifer, John Witter, and Bruce Leutscher. "A Healthy Forest Gives Us...." Forest Health in the North Central States. University of Michigan, School of Natural Resources and Environment, 1998. Web. 10 Aug 2010. <http://fhm.fs.fed.us/pubs/fhncs/chapter1/a_healthy_forest.htm>. My students will be reading the above section of the publication and respond to it at the end of Lesson 1. Teaching and Learning Objectives Throughout this unit students will: Participate in classroom and small group discussions Read and respond to articles in their science journals Complete questions based on classroom activities and readings Record data and observations in their science journals Design and carry out scientific investigations Complete several lab reports Content Expectations Addressed This unit covers the following Biology Content Expectations: B1.1A Generate new questions that can be investigated in the laboratory or field. B1.1B Evaluate the uncertainties or validity of scientific conclusions using an understanding of sources of measurement error, the challenges of controlling variables, accuracy of data analysis, logic of argument, logic of experimental design, and/or the dependence on underlying assumptions. B1.1C Conduct scientific investigations using appropriate tools and techniques (e.g., selecting an instrument that measures the desired quantity—length, volume, weight, time interval, temperature—with the appropriate level of precision). B1.1E Describe a reason for a given conclusion using evidence from an investigation. B1.1f Predict what would happen if the variables, methods, or timing of an investigation were changed. B1.1g Use empirical evidence to explain and critique the reasoning used to draw a scientific conclusion or explanation. B1.1h Design and conduct a systematic scientific investigation that tests a hypothesis. Draw conclusions from data presented in charts or tables. B1.2A Critique whether or not specific questions can be answered through scientific investigations. B1.2f Critique solutions to problems, given criteria and scientific constraints. L2.p4A Classify different organisms based on how they obtain energy for growth and development. (prerequisite) B2.3B Describe how the maintenance of a relatively stable internal environment is required for the continuation of life. L3.p2B Describe common ecological relationships between and among species and their environments (competition, territory, carrying capacity, natural balance, population, dependence, survival, and other biotic and abiotic factors). (prerequisite) L3.p3A Identify the factors in an ecosystem that influence fluctuations in population size. (prerequisite) L3.p3D Predict how changes in one population might affect other populations based upon their relationships in a food web. (prerequisite) L3.p4A Recognize that, and describe how, human beings are part of Earth’s ecosystems. Note that human activities can deliberately or inadvertently alter the equilibrium in ecosystems. (prerequisite) B3.2C Draw the flow of energy through an ecosystem. Predict changes in the food web when one or more organisms are removed. B3.4B Recognize and describe that a great diversity of species increases the chance that at least some living organisms will survive in the face of cataclysmic changes in the environment. B3.4C Examine the negative impact of human activities. This unit covers the following High School English Language Arts Content Expectations: CE 1.2.1 Write, speak, and use images and graphs to understand and discover complex ideas. CE 1.3.7 Participate collaboratively and productively in groups (e.g., response groups, work teams, discussion groups, and committees)—fulfilling roles and responsibilities, posing relevant questions, giving and following instructions, acknowledging and building on ideas and contributions of others to answer questions or to solve problems, and offering dissent courteously. CE 1.4.1 Identify, explore, and refine topics and questions appropriate for research. CE 1.5.1 Use writing, speaking, and visual expression to develop powerful, creative and critical messages. CE 2.1.1 Use a variety of pre-reading and previewing strategies (e.g., acknowledge own prior knowledge, make connections, generate questions, make predictions, scan a text for a particular purpose or audience, analyze text structure and features) to make conscious choices about how to approach the reading based on purpose, genre, level of difficulty, text demands and features. CE 2.1.11 Demonstrate appropriate social skills of audience, group discussion, or work team behavior by listening attentively and with civility to the ideas of others, gaining the floor in respectful ways, posing appropriate questions, and tolerating ambiguity and lack of consensus. Materials Copies of the student handouts from each lesson Props for play (see Lesson 1) PowerPoint – “Healthy or Not?” Science journals dried mustard and water mixture small spades for digging 3’x3’ plastic sheets for placing dirt Ruler Metal or PVC sampling ring – (about 1 square foot, if possible) Earthworm Key Baggies in which to put the worms. Long tape Field guides for different plant species – trees, shrubs, ferns, etc. Access to the internet Classroom and Field Activities Lesson 1 – Healthy Forests Teacher Preparation Collect the following props: o Narrator – a large story book covered with paper and the title – “A Parable of The Salmon Trout River” o Person 1 – sunglasses, day pack, mining hard hat, geologists hammer or gold pan, long white stick, rock o Person 2 – sunglasses, day pack, cowboy hat, irrigation boots, bandanna, shovel o Person 3 – sunglasses, day pack, fishing vest, waders, fly rod, fake insect (or you could use an imaginary one) o Person 4 – sunglasses, day pack, drinking glass, pitcher, water o Person 5 – sunglasses, day pack, shorts, sandals or water shoes, life jacket, paddle o Person 6 – sunglasses, day pack, Earth-day t-shirt, flower o Person 7 – sunglasses, day pack, tie and sport coat, clipboard with paper and writing utensil Print out the play (9 – 10 copies would be sufficient, or you could print out one for each student in the class). A copy of this play is found in the Student Handouts section below. It was adapted from the following website: http://fs.usda.gov/Internet/FSE_DOCUMENTS/stelprdb5073114.pdf Assign students to fill each part, or have the students volunteer for parts. Once parts are assigned, give the students the corresponding props. Send them out into the hallway (or to the back of the room) to do a trial run through. o NOTE: It may be helpful to assign parts the day before you do the play so that students are familiar with their parts. As the performers are practicing, you can introduce the play to the remaining students in the class. Make copies of “A healthy forest gives us…” which can be found at the following website: http://fhm.fs.fed.us/pubs/fhncs/chapter1/a_healthy_forest.htm. Opening Activity Students perform the play. This should take 15 - 20 minutes depending on the actors/actresses you have… Discussion After the play, hold a discussion. Some possible talking points: o What did you think about the 7 blind persons? o Do you think that stuff like this happens in real life? Are people biased according to their own wants/interests? o What is a watershed? Do we have one? o How do you use the watershed? o Does a watershed only include water? o What about forests? How do you (or do you) use our forests? o What would happen if our watershed became unhealthy or disappeared? Homework Hand out “A healthy forest gives us” to each student. A link to this handout is found under Student Handout 2 - “A healthy forest gives us.” Ask students to read the hand out as homework. In student journals, have each student write down the top three characteristics he/she thinks are most important for a healthy forest. Ask students to write about why the three characteristics were most important to them? (If students are confused by these instructions, follow by asking, “How do these characteristics fit into your life or the life of someone you know?”) Student Handout 1: Lesson 1 - Play The “Blind” Persons and the Watershed: A Parable of the Salmon Trout River Watershed Adapted from: http://fs.usda.gov/Internet/FSE_DOCUMENTS/stelprdb5073114.pdf Cast and Needed Props: Narrator – a large story book covered with paper and the title – “A Parable of The Salmon Trout River” Person 1 – sunglasses, day pack, mining hard hat, geologists hammer, long white stick, rock (copper?) Person 2 – sunglasses, day pack, cowboy hat, irrigation boots, bandanna, shovel Person 3 – sunglasses, day pack, fishing vest, waders, fly rod, fake insect Person 4 – sunglasses, day pack, drinking glass, pitcher, water Person 5 – sunglasses, day pack, shorts, sandals or water shoes, life jacket, paddle Person 6 – sunglasses, day pack, Earth-day t-shirt, flower, granola bar Person 7 – sunglasses, day pack, tie and sport coat, clipboard with paper and writing utensil Salmon Trout River Watershed voice Narrator: (Read slowly, as if telling an ancient story.) Once upon a time, seven blind persons from the Land of Stereotypes came to the Salmon Trout River. (Blind persons enter the room at this time. They should shuffle down the aisle with one hand on the shoulder of the person in front.) They all marveled at the rich natural resources the area had to offer. (The group of blind persons stops, pauses, and looks around.) Persons 1 - 7: (in unison) Ooooooooo! Eeeeeeeeeee! Ahhhhhhhhh! (Group should continue shuffling forward). Narrator: Because they were wearing blinders, they travelled together, walking one behind the other, talking and communicating with each other so they would not fall down. Person 1: Whoa! Careful! There’s a log here. Take a big step. (One person at a time, in sequence, help each other over the log, while saying things like “Be careful,” “Let me help you,” etc. Keep shuffling along). Narrator: Soon the seven persons came to a tributary stream. Person 1: Hey, there’s a little creek here… Person 2: (Put a toe in the creek.) Oh, yeah; it’s nice and cool. Person 3: Let’s follow it downstream and see where it leads us. Person 4: Good idea. Narrator: And so they did. More tributaries joined it, and eventually the blind persons were at the banks of the Salmon Trout River. They all marveled at the river… Persons 1 - 7: (in unison) Ooooooooo! Eeeeeeeeeee! Ahhhhhhhhh! (The group begins to explore the river with their hands…) Person 1: (Pull up a rock from the river and bite it.) It’s copper! It’s copper! Person 2: (Notice the river, but look around at the surrounding area.) I’m hungry. Look how hot and dry and flat this land is. Man, I’m hungry. I wonder what kinds of plants I could grow here. Person 3: (Try to catch a mayfly buzzing around you. Catch the bug and examine it.) Perfect! Just what I needed to catch me some fish… Person 4: (Bend down to fill a cup with water and take a big drink.) Mmmm. That sure is some tasty, cold water. Pure, fresh water! Mmmmmm. Person 5: (Wade into the water and notice the twists and turns of the river.) This is the perfect river to go exploring on with a kayak or canoe on. I can’t wait to get out there. Person 6: (Take a big sniff of the air.) Can you smell that? Fresh air and look at these gorgeous flowers. (Pick up a flower and sniff it.) Person 7: (Look around at all of the other blind people and jot down notes on your clipboard.) Hmmmm. Interesting. Narrator: The first person found copper near the river. He/she was a miner and mined copper that the world could use to make important and decorative things. To get the copper from the surrounding hills, to process the copper, and to dissipate the waste, he/she would need water from the river. Person 1: Yes! That’s it! This river is made for mining. Narrator: The second person noticed the level land in the valley and the nearby plains and thought… Person 2: This would be a great place to grow food for all the people in the world. If only there was more rain… Narrator: Then, the second person had an idea. He/she could dig a ditch to divert water out of the river to water the crops. A reservoir could store spring run-off water for when he/she needed it in late summer. As he/she began to dig the ditch, he/she said… Person 2: Surely, this river was made for agriculture. Narrator: The third person was a fisherman/woman. He/she noticed a mayfly flitting above the river and saw a trout jump for it. He/she scrambled for his/her fly fishing rod in excitement. This is a good place for the people of the world to catch fish, he/she thought. As he/she readied his/her first cast, he/she announced… Person 3: There is no doubt in my mind that this river was made for fishing. Narrator: The fourth person was a city mayor. He/she knelt down, tasted the river, and thought… Person 4: My, this water tastes delicious. It would be perfect drinking water for the people of my city. Too bad my city is so far away. If I could get this water to them, I know our city would grow and prosper. Narrator: The mayor wished he/she could create a great city for the world. Suddenly, he/she had an idea. He/she would hire an engineer who could build a dam to hold the river water and then pipe it to his/her city. He/she was pleased and said… Person 4: This river was made for the people of my city to drink! Narrator: The fifth person loved to canoe and kayak. Person 5: Whoa, dude. This river is totally awesome. I could spend all day paddling up and down this river. Narrator: This person though the river would be a great place for the people of the world to spend some peaceful time while getting exercise. While he/she strapped on his/her life jacket, he/she exclaimed… Person 5: This river was made for kayakers and canoe-ers. Narrator: The sixth person was an environmentalist. He/she thought this watershed was so fresh and clean. Person 6: Back where I come from, the Land of the Stereotypes, everything is so polluted. The people have ruined what really matters – nature. I can’t let that happen here. Narrator: Person 6 thought he/she must save the river for future generations of the world. He/she picked up a granola bar and said… Person 6: This river needs to be left alone. Narrator: The last person of the group was a government bureaucrat. He/she wasn’t really blind; just visually impaired. With all of the people competing to use the river in different ways, he/she thought they would need his/her help. Person 7: I will have to regulate all of these people and their ideas for how to use the river. I can show the world how effective our government can be. Narrator: As he/she jotted down notes and figured out a budget to submit to Congress, he/she thought…. Person 7: This river was put here for me to do my part in the world by regulating and enforcing how it will be used. Narrator: At the end of the day, the group was tired. They came together and talked about the Salmon Trout River Watershed. Person 1: Boy, I had a great day. I found lots of copper. This river is made for mining. What do you all think? Person 2: Maybe it could help you with mining, but I think this river was really intended to be used to irrigate farmland. Yes, indeed. This river will be used for farming. Person 3: Whoa! Wait just a minute. This river is made for fishing. Fishing is a much better way to use this resource than farming and mining. (Person 3 scoffs at the others.) Person 4: (Point at persons 1 – 3.) Wrong, wrong, and wrong again! This river is made to help people. The best way we can do that is to provide all of this fresh, clean water to them. This river is made to help satisfy the thirst of the people of my city. Person 5: Hahaha! That is the silliest thing I’ve ever heard. This river is made for people to enjoy the great outdoors and get some exercise by canoeing and kayaking. It’s a well-known fact that Americans are becoming obese. I say, let’s get them all out here to this river. Some fresh air and paddling would do them good. No more excuses! Person 6: Well, you may think you’ve all found the answer, but I have an even better plan. All of your ideas will ruin this river. If we let all of you do what you want with it, there might not be a river left in a few years. I say, the river should be left natural. No one should disturb it. Person 7: Guys and girls; let’s be reasonable. I am here to help you all. I am with the government. We can work this all out so that everyone is happy. (The group seems to ignore person 7 and argues and fights, repeating their claims.) Narrator: The people could not come to a consensus. They would not listen to each other. They continued to shout, and a few of them even called their lawyers. Finally a voice from the watershed said… Watershed Voice: (In a thunder-like, booming voice.) Stop! Stop! Stop! (The group stops fighting and immediately looks around for the source of the voice.) Watershed voice: The Salmon Trout River Watershed is a very big ecosystem. Each person has only considered one part. You must put all of your parts together to understand what a watershed really is. Persons 1 - 7: (in unison) Ooooooooo! Eeeeeeeeeee! Ahhhhhhhhh! Narrator: The seven people listened to the watershed voice. They sat down together, and talked quietly. Although they did not agree on everything, they listened to each other sincerely. Afterwards, the group took off their blinding glasses, and they could see more than they did before. (Persons 1 – 7 take off their glasses. They look around in amazement. They line up to leave, but this time, they are walk more confidently by themselves; no holding on the another shoulder.) Narrator: Even though the group was no longer visually impaired, they traveled together, one beside the other, never to return to the Land of the Stereotypes. They continued to talk and communicate with each other to help each other over any obstacles they encountered in the future, hoping that they would never be blinded again by their own selfish desires. Student Handout 2: Lesson 1 – “A healthy forest gives us…” Handout found at the following website: http://fhm.fs.fed.us/pubs/fhncs/chapter1/a_healthy_forest.htm A healthy forest gives us ... Biodiversity: It is very important to maintain diversity of living organisms in our forest ecosystems. Diversity gives ecosystems stability and helps them deal with various stress factors. From a human perspective, having a variety of organisms present is aesthetically pleasing. In addition, many species may in one way or another benefit people and be of use to us. Some of these uses we already know about, but there also may be other undiscovered uses. The best way to encourage high levels of biodiversity is to have a good mixture of habitats within our forests. This means maintaining a combination of various forest types, tree ages, and species compositions. Healthy forests usually have a mosaic of stand conditions present. Habitat and wildlife: Residents in the United States spend over $6 billion annually on trips where wildlife is the major attraction. Wildlife use different parts of the forest for food, shelter, and protection. Both living and dead trees are important for various wildlife species. Many species are quite specific in the kinds of conditions they need to thrive and therefore they are often associated only with a particular type or age of forest stand. Protection of soil: Forests help to prevent erosion, or the wearing away of soil through the action of wind and water. The canopy of leaves in the forest shields the ground from the hard pounding action of rain, slowing and softening its fall to the forest floor. Plants also contribute organic material to soil which helps soil absorb and hold water. This prevents the water from running off rapidly across the surface, carrying soil with it. Less visible than the movement of large soil particles but equally important, plants in the forest help to prevent the loss of important nutrients from the soil. They keep nutrients from being washed away across the surface of the land by rainfall. Also, by absorbing nutrients efficiently with their large spreading root systems they prevent nutrients from being transported by water deep down into the soil where they would be unavailable to the plants and animals that need them. Protection of water and air: Forests filter large amounts of water and air which flow through them. This filtering action helps trap some kinds of pollutants and remove them from continued circulation. Forests are important in increasing the amount and quality of drinking water available to people and also are important in providing us with oxygen. Products: Forest trees provide us with lumber for building and wood that is used to make a variety of products such as furniture, containers, and paper. The annual value of wood products is approximately $3 billion in both Indiana and Missouri, $8 billion in Minnesota, $9 billion in Michigan, and $15 billion in Wisconsin. Jobs: Forests are linked directly or indirectly to a large number of jobs. There are over 60,000 people employed in forestry-related jobs in Missouri, 80,000 in Indiana, 110,000 in Minnesota, 190,000 in Wisconsin, and 150,000 in Michigan. Recreation: People use forest areas for a great many recreational activities. Hiking, camping, hunting, fishing, skiing, bird watching, and photography are activities people like to do in forests. People value having forests available for these and other recreational uses and enjoy the shelter, shade, and spiritual comfort that the forest provides. Over 830 million visitors were recorded using national forest lands for various recreational activities in 1996. Aesthetics: Forests enhance the beauty of the landscape, providing rich and varied scenery enjoyed by tourists as well as by those who live near the forests. Activities centering around appreciation of the aesthetic nature of forests, such as autumn color touring, are common in the North Central Region. These activities draw a great many visitors to forest areas annually. Forest related tourism and recreation in Michigan accounts for 50,000 jobs, and contributes $3 billion annually to the states economy. Lesson 2 – How Can We Monitor Forest Health Teacher Preparation Biodiversity Draw a chart, similar to the one below, on the chalkboard or marker board with each of the 8 things that a healthy forest gives us (from the homework reading.) Habitat & Soil Air/Water Products Jobs Recreation Aesthetics Wildlife Protection Protection On the computer, open up the PowerPoint presentation – “Healthy or Not” so that it is ready to go later on in the hour… Print off the “Thinking About It” handout, found under the Student Handouts section. You will need one for every 3 or 4 students (students will be doing this in groups.) Print off the earthworm reading (one for each student), found in the Student Handouts section below. Opening Activity When students walk in, have each of them put a check mark under each of the three things that they think were most important from a healthy forest. Small Group Discussions Break students up into groups of 3 or 4. Pass out the “Thinking About It” handout, found in the Student Handouts section. Tell students to discuss possible answers to the questions and then record their thoughts or findings. PowerPoint – Healthy or Not? Open up the PowerPoint presentation – “Healthy or Not” As you go through the presentation, showing students pictures of several forests, have them record in their journals whether or not they feel the forests in the pictures are healthy. After all pictures are shown and rated by individual students, have students get into groups of 2 or 3. Run through the pictures again, encouraging small group discussion. Have students record in their journals again, whether or not they think the forest is healthy or unhealthy. Ask students to support their answer with a brief explanation. Discussion of PowerPoint Did your opinions change after you met in groups? Was it hard to tell just from a picture whether or not a forest was healthy? What, if anything, was missing from the pictures that would allow you to better tell whether or not the forest was healthy? A Closer Look at the Pictures Healthy or Not? (Slides 2 – 5 could be considered unhealthy due to lack of biodiversity on the forest floor, invasive species, and earthworms. Slide 6 shows what a sugar maple forest floor should look like if earthworms were not present.) Discuss why it is important to know things like location, age of the forest, time of year, disturbances and disasters that have recently come through the area, etc. in order to determine forest health. o It is important to look at a variety of measurements when determining forest health. Homework Pass out the Earthworm Reading found in the Student Handouts section. It may be helpful to tell students that although the information in the reading is from Minnesota, the same information still applies to our area. Ask students to read the journal and write a one paragraph reaction to it. If students are confused by what “reaction” means, follow up with some questions: o What did you think the main idea of the reading was? o Does this information apply to your life? If so, how? o Were you surprised by anything in the reading? If so, what? o Did you learn anything new while reading the article? If so, what did you learn? o How can you use this information in the future? Student Handout 1: Lesson 2 – Thinking About It Names: ___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ 1. What do the members of this class feel are the top 3 things that a healthy forest gives us? 2. Are there any characteristics that were left out or were under-represented? If there are, which ones didn’t get many votes? Why do you think this is? 3. How can you relate this activity to the play that we did yesterday? (In other words, are there any connections between the two? If so, what are they?) 4. Do you think the forests in our area are healthy? How do you know? 5. What are some ways we could measure whether or not a forest is healthy? (Think about the 8 things that a healthy forest gives us…) Please list at least 3 specific ways that we could measure forest health. Use the back side of this page, if necessary. Student Handout 2: Lesson 2 – Earthworm Reading Earthworm reading was taken from the following website: http://www.dnr.minnesota.gov/invasives/terrestrialanimals/earthworms/index.html What's the big deal about earthworms in Minnesota? All of the terrestrial earthworms in Minnesota are non-native, invasive species from Europe and Asia (There is a native aquatic species that woodcock eat). At least fifteen non-native terrestrial species have been introduced so far. Studies conducted by the University of Minnesota and forest managers show that at least seven species are invading our hardwood forests and causing the loss of tree seedlings, wildflowers, and ferns. See "What are the harmful effects of non-native earthworms" below for more information. Why aren't there native earthworms in Minnesota? We have no evidence that earthworms ever inhabited Minnesota before European settlement. Even if they did, the glaciers killed any native North American earthworms in our region. For the last 11,000 years since the glaciers receded, Minnesota ecosystems developed without earthworms. There are over 100 species of native North American earthworms in unglaciated areas such as the southeastern U.S. and the Pacific Northwest. However, native species have either been too slow to move northwards on their own or they are not able to survive Minnesota's harsh climate. How did the 15 earthworm species get here? The first earthworms probably arrived with soils and plants brought from Europe. Ships traveling to North America used rocks and soil as ballast which they dumped on shore as they adjusted the ballast weight of the ship. During the late 1800's and early 1900's many European settlers imported European plants that likely had earthworms or earthworm cocoons (egg cases) in their soils. More recently, the widespread use of earthworms as fishing bait has spread them to more remote areas of the state. All common bait worms are non-native species, including those sold as "night crawlers," "Canadian crawlers," "leaf worms," or "angle worms." What are the harmful effects of non-native earthworms? Minnesota's hardwood forests developed in the absence of earthworms. Without worms, fallen leaves decompose slowly, creating a spongy layer of organic "duff." This duff layer is the natural growing environment for native woodland wildflowers. It also provides habitat for ground-dwelling animals and helps prevent soil erosion. Invading earthworms eat the leaves that create the duff layer and are capable of eliminating it completely. Big trees survive, but many young seedlings perish, along with many ferns and wildflowers. Some species return after the initial invasion, but others disappear. In areas heavily infested by earthworms, soil erosion and leaching of nutrients may reduce the productivity of forests and ultimately degrade fish habitat. Without earthworms a lush forest floor. After earthworms invade, much of the beauty is gone. Aren't earthworms good for soil and gardens? It depends. Earthworms create a soil of a certain consistency. For soils that are compacted due to heavy use by agriculture and urbanization, for example, earthworm tunnels can create "macro-pores" to aid the movement of water through the soil. They also help incorporate organic matter into the mineral soil to make more nutrients available to plants. However, in agricultural settings earthworms can also have harmful effects. For instance, their castings (worm excrement) can increase erosion along irrigation ditches. In the urban setting, earthworm burrows can cause lumpy lawns. Relative to simplified ecosystems such as agricultural and urban/suburban soils, earthworm-free hardwood forests in Minnesota have a naturally loose soil with a thick duff layer. Most of our native hardwood forest tree seedlings, wildflowers, and ferns grow best in these conditions. However, when earthworms invade they actually increase the compaction of hardwood forest soils. Compaction decreases water infiltration. Less infiltration combined with the removal of the duff and fallen tree leaves results in increased surface runoff and erosion. If non-native earthworms are already here, isn't it already too late? No. Without humans moving them around, earthworms move slowly, less than a half mile over 100 years. If we stop introducing them we can retain earthworm free areas for a long time. Also, there are many other non-native earthworms available for sale that could have even more harmful effects. Even in areas with earthworms already present, we don't want to risk introducing any of these other species. What about worms in compost piles? Non-native "red wiggler" earthworms are sold and shipped all over the country for home compost piles and vermicomposting (worm composting) operations. Thus far, they are not known to survive Minnesota winters. However, if they or other species are able to survive winter and escape from compost piles they could further harm native forests. If you have a compost pile in a forested area, do not introduce additional non-native earthworms. If you are concerned about spreading non-native worms with your compost, you can kill worms and their eggs by freezing the compost for at least 1 week. Can earthworms be eliminated from forests? Currently there are no economically feasible methods. Preventing earthworm introductions is the best protection. What can I do to help? Don't dump your worms in the woods. It's illegal to release most exotic species into the wild (Minnesota Statutes 84D.06). Dispose of unwanted bait in the trash. Tell others "the dirt" on invasive earthworms in Minnesota. For more information on invasive, non-native earthworms and other ways to help, visit Minnesota Worm Watch Written by Andy Holdsworth, Cindy Hale, and Lee Frelich (University of Minnesota Center for Hardwood Ecology) and reviewed by the Minnesota Interagency Exotic Earthworm Team - March 2003. Lesson 3 – Monitoring Forest Health – Earthworm Sampling Background Information The area we will be studying surrounds a designated trout lake; this means that people are not supposed to use live bait when fishing. While cleaning up the area, however, my students and I have found earthworm containers. We will study the surrounding area to see how far the earthworms have spread into the forest. Teacher Preparation Teacher should review pages 24 and 29 of the 2010 Michigan Fishing Guide. If possible, have the pages open so that after the discussion, it can be projected for students to see. Teacher should have copies of the two sampling techniques for each student. Both of these techniques can be printed off from the Great Lakes Worm Watch. They are also found under the Student Handouts section, with revisions made for my classroom. Teacher should gather necessary materials for the field trip – every group will need one of the following: o dried mustard and water mixture o small spades for digging o 3’x3’ plastic sheets for placing dirt o Ruler o Metal or PVC sampling ring – (about 1 square foot, if possible) o Data Sheets – Level 1 Plot Surveys from the following website: http://www.nrri.umn.edu/WORMS/team/fielddatasheet-1.pdf o Student Handouts with procedure for Hand Sampling and Mustard Extraction o Earthworm Key o Baggies in which to put the worms. o Writing Utensil (to mark bags and record data) Opening Discussion and Journal Students discuss their reactions to the Earthworm reading Teacher leads a discussion to see what fishermen and women of the classroom know about lake and stream regulations. Questions such as the following may be asked: o How many of you go fishing at Lake Perrault? o Do any of you know of the rules of fishing in Lake Perrault? On an overhead projector, show students information about the lake regulations, found from the DNR website. Pages 24 and 29 of the 2010 Michigan Fishing Guide provide information about different lake regulations as well as the regulations of the lakes in Houghton County. o Interesting points about Lake Perrault: Type D Lake which means… Short season – last Saturday in April – September 30 No live bait allowed Limit is 1 fish All trout and Atlantic salmon must be at least 15 inches long in order to keep (3 – 7 inches longer than other parts of Michigan) Size limit is the same (10 inches) for Coho, Chinook, and Pink salmon Ask students whether or not they think people use live bait on Lake Perrault. Ask students what they think happens to the left over earthworms… Tell students that they will be doing a study to see if there are earthworms invading the forest surrounding Lake Perrault… and if any are found, they will try to determine the extent of them. Introduction to Techniques and Pre-Lab Write Up Students will be introduced to two techniques to search for and collect earthworms, both of which are described on the Great Lakes Worm Watch website: o Mustard Extraction o Hand Sample Students will spend an afternoon out at the lake, sampling for and recording data based on the worms they find. o The Data Sheets are found at the following website: http://www.nrri.umn.edu/WORMS/team/fielddatasheet-1.pdf Students should work on their pre-lab write up, identifying the problem, generating a hypothesis, and recording the materials, safety precautions, and the procedure. Field Trip Divide students into groups of 3 or 4 Hand out sampling equipment and Data Sheets to each group. Allow students to choose a sampling site, but ask that they spread out from the lake into the forest. Students begin with the mustard extraction method, collecting worms in baggies (see the Student Handout section for description of procedure.) Once students have sampled their site for the recommended time, they can move to a site at least 2 feet away to try the hand sample. (Again, see the Student Handout section for the description of this procedure.) Follow Up – Post Field Trip After the earthworms have been collected, students will take the worms back to the classroom for identification. Students write up and submit lab reports. o Lab Reports need to include the following information: (see Evaluation section for rubric) Name/Date Title Problem Hypothesis Materials Safety Procedure Data/Observations Conclusion Possible Extensions Students will have the opportunity to observe and/or dissect the earthworms that we take back to the classroom. Students may build an earthworm box to keep in the classroom so that we can see the effects of earthworms on the forest floor. Students can brainstorm ways to reduce the spread of earthworms through the forest. Students could develop signage to inform the public of the reasoning behind not allowing live bait to be used on Lake Perrault. Student Handout 1: Lesson 3 – Mustard Extraction Method Types of data you can collect using this method: A complete list of the species and/or ecological groups present Relative abundance of different species or ecological groups Density of earthworms on an area basis (i.e. number of earthworms per m²) Biomass on an area basis (i.e. grams of earthworm biomass per m²) Types of data you cannot collect with this method alone: Relative depth of different earthworm species in the upper soil horizons Your teacher will make the mustard mixture before you get to class. The mustard mixture consists of: 1 gallon of water 1/3 cup ground yellow mustard Tips: - Buy ground yellow mustard seed in bulk (you may have to search around or go to a local food co-op), it’s cheaper than buying a large number of small containers. - The extract method will only work when the worms are active. The worms are likely to be dormant if the weather has been consistently hot, cold, or dry. 1. Pick a sampling site. Record the necessary information on the Data Sheet. 2. Label one baggy with the first two letters of the recorders first name, followed by the first two letters of the recorders last name. Then, write the letters “ME” which stands for mustard extraction. 3. Place your sampling ring on top of the soil. 4. Remove any leaf litter or sticks that are inside the ring. Be sure to look for worms within the leaf litter. If you find any worms, record how many on your data sheet, and place the worms in a plastic bag that you labeled in step 2. 5. Push your sampling ring into the soil, so that the mustard mixture will not leak out the sides when you pour it into the ring. 6. Slowly pour about half of your mustard mixture into the ring, letting the liquid soak in as much as possible. 7. Watch for worms to come up. They will begin to emerge in 2 – 10 minutes. 8. Wait until the worms are fully emerged before picking them up, or you might get pieces of worms. You may use forceps, if necessary to pick up the worms. Place the worms in the baggy you labeled in step 2. 9. After 8 – 10 minutes, if no worms are emerging, pour in the remaining mustard solution. 10. Again, wait for worms to emerge fully before picking up. Place any worms you collect in the baggy. Student Handout 2: Lesson 3 – Hand Sampling Method Types of data you can collect using this method: Relative abundance of different species or ecological groups (except the anecic species, Lumbricus terrestris because they will feel the vibrations of you digging and will move out of the area.) Density of earthworms on an area basis (i.e. number of earthworms per m²) Biomass on an area basis (i.e. grams of earthworm biomass per m²) Relative depth of different earthworm species in the upper soil horizons Types of data you cannot collect with this method alone: A complete list of the species and/or ecological groups present 1. Pick a sampling site. Record the necessary information on your Data Sheet. 2. Label one baggy with the first two letters of the recorders first name, followed by the first two letters of the recorders last name. Then, write the letters “HS” which stands for hand sample. 3. Place your sampling ring on top of the soil. 4. Remove any leaf litter or sticks that are inside the ring. Be sure to look for worms within the leaf litter. If you find any worms, record how many on your data sheet, and place the worms in a plastic bag that you labeled in step 2. 5. Take a shovel or hand spade and dig up some soil. Dig to a depth of at least 1 foot to get any endogeic species that might be present. 6. Place soil on one side of a plastic tarp. 7. Sift through it with your fingers looking for worms, moving the soil you’ve looked at to the opposite side of the tarp. NOTE: You should not have to sift the soil through a screen, simply by grabbing handfuls and sifting it through your fingers with reasonable care you will find most of the earthworms present, but be sure to break up clumps of soil, they are often in those clumps. 8. When you are certain that you have collected all the worms at your site, call your teacher over to check. 9. Return the soil to the hole you dug, trying to keep the soil horizons relatively the same. 10. Replace the leaf litter that you took off in step 4. 11. Poke a stick into the middle of your sample site so that other groups know not to dig in the same location. Lesson 4 – Monitoring Forest Health – Biodiversity Study Teacher Preparation Collect leaves from several different species in the area. Collect enough so that each student has their own leaf. Make sure that at least two students in each class have the same leaf. Make copies (one per student) of the Leaf Terminology sheet found in the Student Handouts section. Make copies of the Field Trip Handout from the Student Handouts section. Collect the following materials for the field trip: o Field guides (any for identifying trees, shrubs, ferns, etc.) o Long tape – for measuring the sample area o Students should bring science journals and a writing utensil Opening Activity Students try to make as many observations as they can about their leaf using the Leaf Terminology handout. Students make a guess at the type of tree they have based on the leaf. If time permits, allow students to read off the descriptions of the leaves they have so that they can try to find a partner in the room with the same leaf. Introduction to Field Trip and Pre-Lab Write up Ask students to write in their journals about how they would measure biodiversity in an area. o Some leading questions might be: What would you count? Could you count everything? o Give time for students to write about and share their ideas. o Lead students in a discussion, helping them to discover that they need to count the different kinds of species in the area. Inform students that they will be trying to measure the biodiversity out at a selected site (in our case, Lake Perrault). Students will be working in groups of 3 – 4. All students will need to bring their journals, for drawing and recording the information they find. Each group will be sampling at least two different plots – one will be on the lake side of the site; the other plot will be closer to the fen. o Explain to the students that they will be sampling the two different areas because they are different habitats with different species. o Tell students to keep the information for each habitat separate in their notes. Hand out the Field Trip Handout, which contains the instructions for sampling and measuring biodiversity. It may be helpful to read through the handout with students in case they have any questions. For the purposes of this field trip, we will only be measuring plant biodiversity. o It might be interesting to ask students why we might not be measuring animal diversity (or this could be saved for the post field trip discussion). Students should work on their pre-lab write up, identifying the problem, generating a hypothesis, and recording the materials, safety precautions, and the procedure. Field Trip Students begin by measuring off the area to be sampled. Students identify over story species, and if time permits, any shrubs, ferns, grasses, etc. Encourage students to draw pictures of any species that they aren’t sure of or that they have trouble identifying. It may even be helpful to bring back a leaf from the plant in question. These can be recorded in the science journal. Students should record their data in their science journals. Once students finish one plot, they can move to the next sample plot and repeat the process. Follow Up – Post Field Trip When students return, they will work on their lab reports and submit them. o Lab Reports need to include the following information: (see Evaluation section for rubric) Name/Date Title Problem Hypothesis Materials Safety Procedure Data/Observations Conclusion Students can discuss why they didn’t measure animal species. Once all the data is in, the students can pool their data to see a broader picture of the types of species and amount of biodiversity in the area. Homework In science journals, students decide whether or not it can be determined that a forest is healthy based on biodiversity. Student should support their reasoning with facts, data, and scientific vocabulary. o For a rubric for the science journal entries, see the Evaluation section. Student Handout 1: Lesson 4 – Tree ID GLOSSARY OF TERMS USED IN THIS TREE ID KEY Needle-shaped: More or less, sharp and pointy. Needles, single: Individual attachment to twig. Needles, cluster: A dense group of a dozen or more needles. Needles, bundle: A group of 2-5 needles “bundled” together at their bases. Needles, flat: Much wider than thick. Tends not to roll easily between fingers. Needles, square or round: About as wide as thick. Rolls easily between fingers. Branching, Alternate: Paired side branches do not occur opposite each other from a main twig. Also true for buds and leaf stem “scars.” Branching, opposite: Paired side branches occur on opposite sides of a main twig. Also true for buds and leaf stem “scars.” Leaves, simple: Your basic leaf with one stem and contiguous leaf surface. Leaves, compound: One stem, multiple leaf surfaces (looks like separate leaves). Leaves lobed: Finger-like projections of leaf, like oaks. Chambered pith: Cores of twigs are divided into small chambers. YOUR TREE Has Needles (coniferous or softwood) Needle-Shaped Needles Single Not Needle-Shaped Needles in Clusters Simple Leaves Leaves Lobed Pines Oaks Hawthorne Cedar Flat Needles Balsam Fir Hemlock Douglas-fir Alternate Branching Needles in Bundles Tamarack Larch Has Leaves (deciduous or hardwood) Square or Round Needles Opposite Branching Compound Leaves Simple Leaves Twig Pith Is Chambered Pith Not Chambered Butternut Walnut Hickories Locusts Mtn. Ash Leaves Not Lobed Spruces Douglas-fir Thorns Papery Bark Yellow-gray Bark Wintergreen Flavored Twigs White Bark No Wintergreen Flavor Yellow Birch Paper Birch Upper Peninsula Ashes Boxelder Leaf Margin Smooth Leaf Margin Toothed Sugar Maple Red or Silver Maple Others Aspens Cottonwood Hawthornes Simple identification key for the tree species of the Flattened Leaf Stems Compound Leaves Beech Basswood Cherries Elms Willows Ironwood Musclewood Hackberry Juneberry MSU Upper Peninsula Forestry Extension Office 8/2000. Michigan State University programs and materials are open to all without regard to race, color, national origin, gender, religion, age, disability, political beliefs, sexual orientation, marital status, or family status. Student Handout 2: Lesson 4 – Field Trip Handout Field Trip Handout – Biodiversity Measurements 1. Collect the following materials: Your science journal and a writing utensil Field guides to help you identify the plants in your plots Long tape to help you measure your plot size 2. Starting near the lake, pick a sample site to measure the plant biodiversity. 3. Identify a starting point that will act as the center or your plot. 4. Using your long tape, measure a radius of 37.24 feet. This will give you a sample plot that is 1/10th of an acre. 5. Use fallen sticks to create the boundaries of your sample plot. 6. Begin identifying the over story species in your plot. (Use your field guides to help you along with the MSU Extension Simple Identification key. 7. Record the species and number of trees of each species in your science journal. 8. If you are having trouble identifying a species, draw it and take a leaf sample from the tree, if possible. 9. Once you have the over story species, begin identifying the under story species, using your field guides. 10. Record the species and number of each species in your science journals. 11. When you are confident that you have identified as many plant species as you can, move on to the next sample area – closer to the fen. 12. Repeat the same process for your second sample area. Lesson 5– Monitoring Forest Health – Salamander Study Teacher Preparation NOTE: The information for this lesson was taken from the Terrestrial Salamander Monitoring and Terrestrial Salamanders of Michigan handouts that were developed by Meagan L. Harless for the 2010 Forest Ecology Institute at Michigan Technological University. The information from this handout is found in the Teacher Background Information and Instructions section. Make copies of the Student Handouts. o It may be helpful to laminate the Terrestrial Salamanders of Michigan Handout. Teacher should place Artificial Cover Objects in the area to be sampled at least several weeks before the study is to take place. Teacher Background Information and Instructions The following information can be printed as a Student Handout or as something that can be talked about in a whole class discussion. It may be helpful for students to have a list of potential research questions as well as the instructions for searching for salamanders for the experiments they are going to write and carry out. What makes salamanders unique? o Amphibians – in family Amphibia, which includes frogs, toads, and caecilians o 521 species worldwide; 178 species in the United States; 10 species in Michigan o Most have 4 toes on front limbs and 5 toes on rear limbs o Ectothermic o Skin is thin and permeable – avoid high temperatures and dry areas o Secrete mucous to protect skin o Can regenerate lost limbs o Tail autotomy – can break off a portion of their tail to distract predators Where do we find salamanders? o Streams o Lakes o Wetlands o Moist forests o Under rocks and rotting logs What salamanders are found in Michigan? o 8 terrestrial/semi-terrestrial species o 2 aquatic species o Most common terrestrial – Red-backed and blue-spotted o Rarest terrestrial – marbled and small-mouthed Why monitor salamander populations? o Vulnerable to habitat alteration, pollution, and climate change o Critical part of ecosystems Control invertebrate populations Supply energy and nutrients to tertiary consumers Provide a connection between aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems Contribute to soil dynamics o Amphibians have been declining rapidly over the past few years Their disappearance would be devastating o Can monitor local species diversity and abundance Ways to monitor salamanders o 1- Artificial Cover Objects (ACOs) Used to determine species diversity and abundance Advantages Non-disruptive and does not destroy habitat o Inexpensive and long-lasting materials Little set up time Easy to complete data collection Project design can be altered to accommodate research questions Disadvantages May not adequately sample all salamander species May not be used by salamanders in areas with many natural cover objects Require one to two years to rot to become ideal salamander habitats Weather may influence ability to see salamanders Materials 2”x4” boards o Untreated green oak pieces are the best option o NOTE: DO NOT use plywood because it contains toxic chemicals and would kill the salamanders. o Other eco-friendly materials Clay plates, dinner plates, bricks o NOTE: Do not use tin. It heats up and would not provide a suitable habitat for salamanders, but you might find some snakes! Compasses and/or GPS units Long measuring tape Markers or something else to label the ACOs Flagging Data collection sheets and a writing utensil Any other materials needed to answer the research question Set up Typical transects consist of 10 boards with 10 meters in between each board Place boards in areas with known salamander populations. (Moist, mature woodlands near streams or vernal pools.) Make sure ACOs are placed flush on top of leaf litter. Remove any sticks or rocks, if necessary. Data Collection ACOs should be checked 4 times per year – early spring, mid to late spring, fall, and late fall At least 1 – 2 weeks should pass between ACO checks. Ideal times to check ACOs are after substantial rainfall and in cool weather. When checking the ACOs, students should lift the boards so that it opens away from them. This way, anything under the boards will run away from the students. Students need to be fast in looking for and trying to identify any fleeing salamanders. Potential Research Questions Do salamanders prefer one type or size ACO over another? In what weather conditions or seasons do we find more salamanders? In what types of habitats are coverboards most productive? Do other habitat variables such as over story/ under story cover or dominant habitat type affect coverboard use? Do any of these variables correlate to the diversity of salamander species using the ACOs? Do transects in a north – south or east – west direction have different amounts or species of salamanders? 2 – Visual Encounter Surveys: Area-constrained Searches Used to determine density and species diversity in defined plots Advantages Inexpensive and no equipment required Short time to collect data Project design can be altered to fit research questions. Disadvantages May not adequately sample all salamander species May be influenced by the weather at the time of the survey May destroy or alter habitat Materials Compasses and/or GPS units Long measuring tape Markers or something else to label the ACOs Flagging Data collection sheets and a writing utensil Any other materials needed to answer the research question Set up Choose and number study sites before taking a field trip Plots or transects should be delineated to cover a significant portion of the available habitat. Observers can cover pre-determined size paths within the plot. Students will search for salamanders by looking under logs, rocks, in the leaf litter, and bark piles, but should replace all objects to their original positions after they have checked under the object. Data Collection Transects should be completed 4 times per year – early spring, mid to late spring, fall, and late fall At least 1 – 2 weeks should pass between transect checks. Ideal times to check transects are after substantial rainfall and in cool weather. When checking the transects, students should lift the boards so that it opens away from them. This way, anything under the boards will run away from the students. Students need to be fast in looking for and trying to identify any fleeing salamanders. Potential Research Questions In what weather conditions or seasons do we find more salamanders? Do other habitat variables, such as over story/ under story cover or dominant habitat type affect salamander density? Do transects in a north – south or east – west direction have different amounts or species of salamanders? Opening Activity Have students create a KWL Chart for Salamanders. (K = what they already know; W = what they want to learn; L = what they learned from the experience the L part will be filled out after the field trip). It might be helpful to provide the students with some potential research questions. Introduction to Field Trip After students fill out the K and W parts of their chart, have a discussion with the class to determine what the students are interested in studying in regards to salamanders. Encourage students to come up with other research questions that they could answer. Keep a list of the research questions of the students. Divide groups into 3 – 4 based on which research question they’d like to answer. In Class and Homework Have students develop a procedure that could help them come up with an answer to their research question. Encourage students to work together with their groups. o NOTE: Students may need more than one class period and meetings with the teacher to develop a procedure. Remind students to think about the variables (dependent and independent) of their study. Students should try to come up with a control group, if possible. Check students’ procedures and have them revise, if necessary. Field Trip Have students get into groups based on the research question and procedures they developed. Remind students of some of the safety information and reminders involved in the salamander study. o Pick up the boards so that the side you lift the board away from you. o Try not to touch the salamanders, especially if you are wearing bug spray (salamanders have thin skin!) o Put the boards/logs back where you found them… the boards and logs are the salamanders’ houses! Pass out the Terrestrial Salamanders of Michigan handout to each group. Tell students to record their data in their science journals. This field trip will be repeated several times throughout the year – early fall, late fall, early spring and late spring. Follow Up – Post Field Trip Students should fill out the L portion of their KWL charts and hand them in. Each group can share their data with the class. Students should complete and turn in their lab reports. o NOTE: Some students may not have an answer to their research question until after the last field trip in late spring. Evaluation Students will be evaluated on the following: Participation in all classroom and field trip activities and discussions. o Students can earn up to 3 points per day for coming to class prepared, having homework and readings complete, and participating in classroom discussions and activities. o Bonus points can be earned for participating in extra activities (like the play). Completion of science journals o See the Rubrics section for a detailed rubric on grading. KWL chart o Students can earn up to 10 points for completing the KWL chart with thoughtful responses and timeliness. Completion of Lab Reports o See the Rubrics section for detailed information on how the lab reports will be scored. Rubrics Science Journal Rubric Name: ______________________________________ ________________________________ Date: ______________________________________ Student science journals will be assessed for: overall quality completeness accuracy effort communication of thoughts Use the rubric below for more specific grading information. Standard 0 = Not demonstrated 1 = Developing 2 = Proficient 3 = Exemplary Journal is organized and neat. Student uses scientific vocabulary. Student makes adequate notes and explanations. Student uses diagrams and illustrations to communicate ideas. Student generates unique and creative ideas that relate to the topic. Journal was turned in on time (lose 1 pt for each day late). All journal entries are marked with the proper date. All journal entries are complete. 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 Student’s name is on the front of the journal. 0 1 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 Total: _________________/25 Science Lab Report Rubric Name: ______________________________________ ________________________________ Date: ______________________________________ Standard 0 = Not demonstrated 1 = Developing 2 = Proficient 3 = Exemplary Lab report is legibly written (or typed) in blue or black ink (no torn or wrinkled pages). Lab sections are found in the correct order 0 Lab contains few to no spelling or grammar mistakes. 0 Your name is first, followed by your lab partners’ names. 0 The date is accurate (the day we started the actual lab). 0 Descriptive title is included. 0 The problem is accurately described. 0 Hypothesis is correctly written (if/then statement). 0 All lab materials are listed so that someone could repeat the lab. 0 Student makes note of any safety concerns for the lab. 0 Procedure is written so that someone could repeat the lab. 0 Data is accurately recorded during experimentation. 0 Data is neatly organized and is easy to interpret. 0 All data also has the correct units attached to it, if necessary. 0 Conclusion states whether or not hypothesis was supported (uses exp. data). 0 Conclusion includes any sources of error. 0 Lab report turned in on time (one point lost for each day late). 0 0 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 Total: _________________/50