relative truth-paper

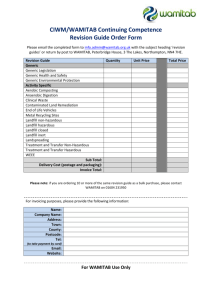

advertisement