Chapter 10

advertisement

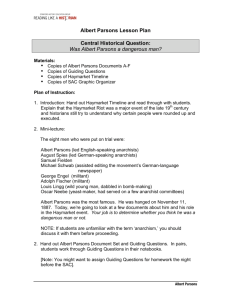

Chapter 10 The Social System—Talcott Parsons Chapter Objectives: After reading and understanding this chapter, a student should be able to Discuss the systems approach to understanding society Explain how social systems are formed through modes of orientation, types of action, and through roles, norms, and status positions Describe a system’s functional requisites and interstructural relations using Parsons’s AGIL analytical scheme Explain how the cybernetic hierarchy of control works and its importance for understanding how society functions Discuss the process of social change through the ascendancy of a social movement through the equilibration of the system Discuss the differences between modernism and postmodernism in terms of the kind of theory each wants to produce and be able to explain the significance of neo-tribes Chapter Outline: I. Parsons Perspective: Abstract Social Systems Key concepts: system; boundary negotiation; integration; generalized media of exchange; equilibrium; analytic theory; institutionalization A. Society as a system 1. Two problems that systems must solve to exist a. Relationship with boundary b. Internal integration 2. Two qualities of Parsons’s systems theory a. Generalized media of exchange: ways that structures within a system talk to one another b. Equilibrium: systems will tend toward equilibrated states (balance between integrating and dividing forces) B. Analytic theory 1. Parsons doesn’t give a theory capable of predicting only explaining— it’s an analytical scheme that can be used to understand diverse social systems II. The Making of the Social System Key concepts: voluntaristic action; action theory; the unit act; normative influence; modes or orientation; cognitive, appreciative, and moral values; cognitive, cathectic, and evaluative motives; status positions; roles; norms; social system A. Voluntaristic action 1. Other theories of action: Weber and Mead 2. Parsons wants to understand the context of action B. The unit act 1. The most basic unit of analysis: goal oriented action 2. Each act contains two important elements: the conditions of action and the means of action a. Little agency with conditions of action; agency with means of action; however, means and goals are normatively circumscribed Parsons’s beginning question: how is action normatively circumscribed? C. Constraint of action (Figure 10.2) 1. In every action there are motivations and values—energy to act and a hierarchy of value—together these form the person’s mode of orientation 2. Three kinds of value: cognitive, appreciative, and moral 3. Three kinds of motivations: cognitive, cathectic, and evaluative 4. These values and motivations form three types of culture patterns a. Belief systems of cognitive significance b. Systems of expressive symbolism c. Systems of value-orientation standards 5. Together, the modes of orientation and culture patterns produce three distinct types of action a. Strategic action b. Expressive action c. Moral action D. Institutionalization—patterning of voluntaristic actions (Figure 10.3) III. System Functions and Control Key concepts: adaptation; goal attainment; integration; latent pattern maintenance; socialization; cybernetic hierarchy of control A. System needs—Parsons’s four generalized requisite needs—AGIL (Figure 10.4) 1. Adaptation: negotiates the boundary between the system and environment; the subsystem that converts raw materials from the environment into usable stuffs (in the body, the digestive system; in society, the economy) 2. Goal attainment: the subsystem that motivates and guides the system as a whole (in the body, the mind; in society, government) 3. Integration: the subsystem that regulates the activities of the systems diverse members (in the body, the central nervous system; in society, the law) 4. Latent pattern maintenance: the subsystem that indirectly preserves patterns of behavior that are needed for survival (in the body, the autonomic nervous system; in society, education, religion, and family) a. Socialization B. Systemic relations (Figure 10.5) 1. Institutional analysis that looks at the relationship among and between different institutionalized structures in society 2. Parsons looks at institutional boundary exchanges C. Cybernetic hierarchy of control (Figure 10.6) 1. The social system itself is a sub-system that exists within an environment of systems (the culture system, social system, personality, system, organic system) 2. The relations among these different sub-systems can be analyzed through AGIL relations 3. Energy flows up; control down from culture system—thus making this a cybernetic hierarchy of control IV. Social Change Key concepts: equilibrium; cultural strain; alienative motivational elements; A. Equilibrium and cultural strain 1. Systems tend toward equilibrium 2. But the process of culture generalization can bring conflicts (fundamentalism), which brings cultural strain B. Revolution 1. Social change occurs in two phases a. Ascendancy of the revolutionary movement b. Adaptation of the movement (re-equilibrating process) 2. Four conditions for ascendancy of revolutionary movement a. Alienative motivational elements (motivation that comes from value inconsistencies—more likely the more general the culture) b. Subculture formation: subculture enables members to evade sanctions of the main group, create solidarity, create an alternative set of normative expectations and sanctions, and it enables expressive leadership to arise c. Formation of ideological legitimation—added by i. Central value system of large societies is often very general and is therefore susceptible to appropriation by deviant movements ii. Serious strains and inconsistencies in the implementation of societal values create legitimacy gaps that can be exploited by the revolutionary group d. Institutionalization of movement (re-equilibration) i. The utopian ideology that was necessary to create group solidarity must bend in order to make concessions to the adaptive structures of society ii. The unstructured motivational component of the movement must be structured toward its central values. The movement must institutionalize its values both in terms of organizations and individuals iii. Out groups must be disciplined vis-à-vis the revolutionary values that are now the new values of society V. Thinking About Modernity and Postmodernity Key concepts: logocentricism; neo-tribes A. Parsons, science, and modernism 1. Science as a grand narrative a. Part of project of Enlightenment b. Value system—belief in objective knowledge, progress, and technical control c. Belief in cumulation i. Produces grand narrative ii. Logocentricism: validation of scientific works by citation; excludes all other work B. Sociological and social theories 1. Sociological theory concerned with description and objective cumulation of knowledge 2. Social theory concerned with critical knowledge and inciting social discourse and change C. Complex systems and neo-tribes 1. Parsons’s systems theory: comparatively stable, tend towards equilibrium, and have rather predicable results 2. Postmodernism characterized by complex systems: unpredictable and not controlled by statistically significant factors 3. Neo-tribes as an example of flexible and unpredictable identities in postmodernity Chapter Summary: Parsons is the individual who is usually associated with clearly articulating a systems approach in sociology. This kind of theoretical method encourages us to see society in terms of system pressures and needs. Two issues in particular are important: the boundary between the system and its environment and the internal processes of integration. Parsons divides each of these into two distinct functions. External boundaries are maintained through adaptation and goal attainment; internal process functions are fulfilled by integration and latent pattern maintenance. Systems theory also encourages us to pay attention to the boundaries between subsystems, in terms of their exchanges and communication. Because relatively smart or open systems have goal states, take in information, and contain control mechanisms, they tend toward equilibrium. Parsons conceptualizes society as just such a system. Additionally, because Parsons sees everything operating systemically, his theory is cast at a very abstract level and intended to be applied to any and all systems Parsons builds his theory of the social system from the ground up. He begins with voluntaristic action occurring within the unit act. Humans exercise a great deal of agency in their decisions; however, their decisions are also circumscribed by the situation and normative expectations. The normative expectations in particular are where human agency is most expressed and where culturally informed motives and values hold sway. These different motives and values orient the actor to the situation and combine to create three general types of action: strategic, expressive, and moral. People tend to interact socially with those who share their general types of action. As a result, interactions become patterned in specific ways, which, in turn, tend to create sets of status positions, roles, and norms. We may say that status positions, roles, and norms are institutionalized to the degree that people pattern their behaviors according to such sets and internalize the motives, values, and cultures associated with them. Different sets of institutionalized status positions, roles, and norms are clustered around different societal needs. Because society functions as a system, there are four general needs that must be met: adaptation, goal attainment, integration, and latent pattern maintenance. In complex, differentiated societies, these functions are met by separate institutional spheres. The different institutions are integrated through the system pressures of mutual dependency and generalized media of exchange. The social system itself is only one of four systems that surround human behavior. There are the cultural, social, personality, and physical systems, each corresponding to AGIL functional requisites. Because systems are dependent upon information, the culture system is at the top. Information flows from the top down, and the energy upon which culture is dependent flows from the bottom up. Parsons refers to this scheme as the cybernetic hierarchy of control. Systems tend toward equilibrium. They can, however, run amiss if the subsystems are not properly integrated. In the social system this happens through cultural strain. As societies become more differentiated, the media of exchange must become more general. In this process, it is possible that some groups will seek to hold onto the dysfunctional culture. This case sets up a strain within the system, with some subsystems or groups refusing to change and other subsystems moving ahead. Motivation for social revolution is possible under these conditions. After people are motivated to change society, they must then create a subculture that can function to unite their group and create an alternative set of norms and values. This culture must eventually have wide enough appeal to successfully make a claim to legitimacy. In a revolution, either side could win (the reformers or the fundamentalists), but in either case certain steps are systemically required to reintegrate the system. After the revolution, the subgroup must produce a culture that can unite the system. Institutionalization occurs at this point as it does at every point: through behaviors patterned and people socialized around a set of status positions, roles, and norms. Parsons’s theory allows us to focus on some of the broader, more fundamental issues represented by postmodern theory. Postmodern theory proposes that society has changed at its core; in the way it works—society no longer functions as a predictable system. Society is better understood in postmodernity in terms of complex or chaotic systems. Simply, this means that social elements can combine in non-linear and undetermined ways. Bauman’s notion of neo-tribes is a good example of this thinking. Postmodernism also challenges the way in which we construct knowledge. Thus, postmodernism isn’t simply about the possibility that we may be living in a new kind of social world; it is also a critique of how we know what we know. Science and its methods are value laden; they came into existence in response to and support of the nation-state and Western colonialism. Science produces technologies of control, for both the physical and human environments, and is thus a part of modernist philosophy. The objectifying, linear way of knowing must be set aside for more subjective, language based ways of knowing. Rather than giving truth-value over to one voice (science), we must give equal place to multiple voices. Rather than seeking to control the social world, we must reflexively place ourselves within the context and collectively work through inclusion and dialog to allow social worlds to emerge.