JML2000

advertisement

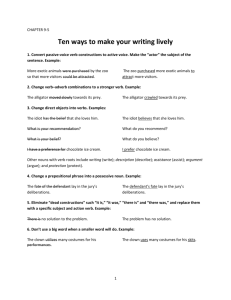

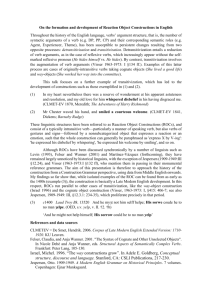

Running Head: Argument Structure Constructions The Contribution of Argument Structure Constructions to Sentence Meaning Giulia M. L. Bencini Adele E. Goldberg Department of Linguistics University of Illinois Urbana IL 61801 Argument Structure Constructions 2 Argument Structure Constructions 3 Abstract What types of linguistic information do people use to construct the meaning of a sentence? Most linguistic theories and psycholinguistic models of sentence comprehension assume that the main determinant of sentence meaning is the verb. This idea was argued explicitly in Healy and Miller (1970). When asked to sort sentences according to their meaning, Healy and Miller found that participants were more likely to sort sentences according to the main verb in the sentence than according to the subject argument. On the basis of these results, the authors concluded that the verb was the main determinant of sentence meaning. In this study we used the same sorting paradigm to explore the possibility that there is another strong influence on sentence interpretation: the configuration of complements (the argument structure construction). Our results showed that participants did produce sorts by construction, despite a welldocumented tendency for subjects to sort on the basis of a single dimension, which would favor sorts by verb. Argument Structure Constructions 4 The relationship between verb, sentence form and sentence meaning has been at the center of linguistic theory and psycholinguistic models of sentence processing for several decades. Within linguistic theory, the predominant view since Chomsky (1965) has been that the lexical representation of a verb specifies (or projects) the number and types of arguments corresponding to the participants in the event described by the verb (its subcategorization frame or argument structure1). This view suggests that the verb is the best predictor of general sentence interpretation. For example the lexical representation for give would specify that it requires three arguments: a subject, a direct object and an indirect object as illustrated by the sentence: Pat gave a cookie to Kim. We will refer to this view as the verb-centered view. The relationships between sentences with the same lexical items but different argument structures (alternations) have been captured by positing lexical rules or transformations; the two sentences have often been assumed not to differ importantly in meaning (following Katz, 1964). For example, the ditransitive in (1a) has been argued to be derived from (1b) by lexical rule or transformation with little change in meaning (e.g., Larson, 1988). (1) a. Pat gave Kim a cookie b. Pat gave a cookie to Kim Most psycholinguistic models of sentence comprehension and production also assume that argument structure information is encoded in the verb. Experimental evidence has demonstrated that the main verb is in fact a critical factor in sentence comprehension. Verb-specific statistical preferences for particular argument structures have been shown to affect the on-line processing of temporarily ambiguous sentences (Garnsey, Pearlmutter, Myers & Lotocky, 1997; Trueswell, Tanenhaus & Kello, 1993). Lexicalist models of sentence comprehension (Boland & Boehm-Jernigan, 1998; Juliano Argument Structure Constructions 5 & Tanenhaus, 1994; MacDonald, Pearlmutter & Seidenberg, 1994) capture the effects of argument structure biases by assuming that argument structures are probabilistically associated with the lexical representation of verbs, and are available as soon as the verb is recognized. Building on the sentence production model of Levelt (1989) and Levelt et al. (1999), in which syntactic information about the verb is represented in a separate lemma stratum, Pickering and Branigan (1998) proposed that the argument structure possibilities for a verb are also part of the lemma information for that verb along with category type and syntactic feature information (number, person, gender). Although these models allow for one verb to be probabilistically associated with more than one argument structure, they still assume that the verb is the main determinant of syntactic and semantic information about the sentence. An early study that specifically looked at the contribution of the main verb to the overall meaning of the sentence is one by Healy and Miller (1970). The authors compared the relative contribution of verbs and subject arguments to overall sentence meaning. They constructed 25 sentences by crossing 5 subject arguments (the salesman, the writer, the critic, the student, the publisher), 5 verbs (sold, wrote, criticized, studied, published) and one patient (the book). Participants sorted the sentences according to similarity in meaning. Results showed that participants sorted sentences together that had the same verb much more often than sentences that had the same subject argument. Healy and Miller concluded that the verb is the main determinant of sentence meaning. It does seem to be true that of all the words in a sentence, verbs are the ones that carry the most information about the syntax and the semantics of the sentence. Because of the high predictive value of verbs, it is reasonable to assume that people use this information during comprehension to predict other lexical items in the sentence and the overall meaning of the sentence. Conversely, given a message to be expressed, speakers can use information about the verb to activate lexical items and syntactic forms. Two additional observations, however, suggest that the predictive value of verbs with Argument Structure Constructions 6 respect to the overall meaning of the sentence may not be as strong as assumed by traditional linguistic theories, nor as suggested by Healy and Miller (1970). The first observation is that verbs occur in many more argument structure configurations than is generally assumed (Goldberg, 1995; Rappaport Hovav & Levin, 1998). For example kick, which is traditionally considered to be a prototypical transitive verb, can occur in at least eight argument structure frames: 1. Pat kicked the wall 2. Pat kicked Bob black and blue 3. Pat kicked the football into the stadium 4. Pat kicked at the football 5. Pat kicked her foot against the chair 6. Pat kicked Bob the football 7. Horses kick 8. Pat kicked his way out of the operating room The sentences in 1-8 designate a variety of event types including simple transitive action (1), caused change of state (2), caused motion (3), attempted action (4), transfer (6), and motion of the subject referent (8). Second, even when the predominant treatment of argument structure alternations was the transformational one, many linguists recognized that argument structure configurations are associated with systematic variations in meaning (Anderson, 1971; Borkin, 1974; Fillmore, 1968; Partee, 1965; Wierzbicka, 1988). With respect to the dative alternation in (2) and (3), Partee (1965), for example, noted that the ditransitive argument structure requires that the goal argument be animate, while this is not true of the paraphrase with to: (2) Argument Structure Constructions 7 a. I brought a glass of water to Pat b. I brought Pat a glass of water (ditransitive) (3) a. I brought a glass of water to the table b. *I brought the table a glass of water (ditransitive) One way to account for these variations in meaning is to posit a different verb sense for each possible argument structure configuration (Levin & Rappaport Hovav, 1995; Pinker, 1989), hereafter the multiple-verb-sense approach. In the multiple-sense view, bring in I brought a glass of water to Pat is argued to be a different sense than bring in I brought Pat a glass of water, and ran in Chris ran home is argued to be a different than ran in Chris ran. Psychologically, the multiple-sense view translates into assuming different long-term representations for each verb sense which are stored in the mental lexicon. In production, then, the speaker would select the appropriate sense from the mental lexicon, and this in turn would be associated with a unique argument structure pattern. In comprehension, the task is more complicated, because in English there are no overt markings on the verb that could cue the comprehender as to which sense is intended. Therefore, the comprehender would have to observe the argument structure configuration, reason backwards to the semantic interpretation that is assumed to have produced that configuration, and select the corresponding sense. An alternative way to account for alternations and the fact that verbs occur in many argument structure patterns is to assign meaning directly to various abstract argument structure types, thereby recognizing the argument structure patterns as linguistic units in their own right. We refer to this approach as the constructional approach (Fillmore & Kay, 1999; Goldberg, 1995; Jackendoff, 1997; Michaelis & Lambrecht, 1996; Rappaport Hovav & Levin, 1998). Examples of English argument structure constructions with their forms and proposed meanings are shown in Table 1. Argument Structure Constructions 8 ******************************** * Insert Table 1 about here. * ******************************** On this view, argument structure patterns contribute directly to the overall meaning of a sentence, and a division of labor can be posited between the meaning of the construction and the meaning of the verb in a sentence. While the constructional meaning may, perhaps prototypically, be redundant with that of the main verb, the verb and construction may contribute distinct aspects of meaning to the overall interpretation. For example, the ditransitive construction has been argued to be associated with the meaning of transfer or “giving” (Goldberg, 1995; Green, 1974; Pinker, 1989). When this construction is used with give, as in Kim gave Pat a book, the contribution of the construction is wholly redundant with the meaning of the verb. The same is true when the construction is used with send, mail, and hand. As is clear from these latter verbs, lexical items typically have a richer core meaning than the meanings of abstract constructions. In many cases, however, the meaning of the construction contributes an aspect of meaning to the overall interpretation that is not evident in the verb in isolation. For example the verb kick need not entail or imply transfer (cf. Kim kicked the wall). Yet when kick appears in the ditransitive construction, the notion of transfer is entailed. The ditransitive construction itself appears to contribute this aspect of meaning to the sentence. That is, the sentence Kim kicked Pat the ball can be roughly paraphrased as “Kim caused Pat to receive the ball by kicking it”. The construction contributes the overall meaning of “X causes Y to receive Z”, while the verb specifies the means by which the transfer is achieved, i.e. the act of kicking. On this view, it is a conventional fact of English grammar that the pattern “Subject Verb Object1 Object2” is productively associated with the meaning of transfer; many other languages do not have this pattern, Argument Structure Constructions 9 and others have it with a narrower or broader range of meanings. Although this study does not attempt to discriminate between the multiple-verb sense view and the constructional view, we will return to a comparison of the two approaches in the General Discussion. The two experiments reported here were designed to test whether argument structure constructions play a role in determining sentence meaning. Both experiments used a sorting paradigm (Healy & Miller, 1970) in which participants were asked to sort sentences according to their overall meaning. The stimuli consisted of 16 sentences obtained by crossing four constructions and four verbs. That is, there were four sets of sentences which contained the same verb (four sentences each with throw, take, get and slice), and there were four instances of each of the transitive, ditransitive, causedmotion and resultative constructions. The use of a sorting paradigm is a particularly stringent test to detect the role of argument structure constructions. Research in the category formation literature has shown that there is a strong domain-independent bias towards performing unidimensional sorts, even with categories that are designed to resist such unidimensional sorts in favor of a sort based on a family resemblance structure. For example, in a series of experiments, Medin et al. (1987) found that participants persistently performed unidimensional sorts, despite the fact that the category and stimulus structures were designed to induce family resemblance sorting (Rosch & Mervis, 1975). The unidimensional bias was found across a variety of stimulus materials (pictures and verbal descriptions), procedures (on-line and from memory), and instructions. The unidimensional bias was not eliminated by adding complexity to the stimuli nor by adding individuating information to the exemplars. Participants sorted unidimensionally even when they were explicitly told to pay attention to all of the dimensions of the stimuli. Unidimensional sorting has been found even with large numbers of dimensions (Smith, 1981), ternary values on each dimension (Ahn & Medin, Argument Structure Constructions 10 1992), holistic stimuli, and stimuli for which an obvious multidimensional descriptor was available (Regehr & Brooks, 1995). Lassaline and Murphy (1996) hypothesized that the reason participants do not sort categories according to family resemblance even when the category has a family resemblance structure is that family resemblance sorting is computationally more difficult. It requires attending to information across different dimensions and identifying the relations among them. Given the choice, people will take the easier route and sort unidimensionally. In the stimuli used in both of our experiments, the verb provides a concrete shared dimension among subsets of sentences. In the light of the studies just cited, this is an invitation to perform a sort based solely on the verb. In contrast, sentences that share the same construction need not (and in this study, did not) have anything concrete in common; their similarity is abstract and relational, requiring the recognition that several grammatical relations co-occur. It would of course be possible to design stimuli with a great deal of overlapping propositional content such that we could a priori predict either a verb or constructional sort. For example, the sentences Pat shot the duck and Pat shot the duck dead would very likely be grouped together on the basis of overall meaning, despite the fact that the constructions are distinct. Conversely, Pat shot the elephant and Patricia stabbed a pachyderm would likely be grouped together despite the fact that no exact words are shared. Our stimuli were designed to minimize such contentful overlap contributed by anything other than the lexical verb. No other lexical items in the stimuli were identical or near synonyms. Thus, we manipulated the stimuli such that we could compare the contribution of the verbs with the contribution of the constructions. Verb-centered approaches predict that the verb should be an excellent predictor of overall sentence meaning. Because the verb also provides a route to a simple unidimensional sort, these approaches predict that subjects would sort overwhelmingly Argument Structure Constructions 11 on the basis of the main verb. Both the constructional approach and the multiple-verb sense approach, albeit for different reasons, described below, predict that the argument structure configuration should play a critical role in determining meaning. Therefore at least some constructional sorts would be expected to occur. Experiment 1 Method Participants. Seventeen University of Illinois students from an introductory course in linguistics volunteered to participate. These students had not been introduced to syntactic theory or the notion of constructions. Stimuli. Sixteen English sentences were used, obtained by crossing four verbs with four constructions. Each sentence was printed in the center of a 2x3 index card. The verbs were throw, slice, get, and take. The constructions were: ditransitive, caused motion, resultative and transitive, as shown in Table 1. No content words other than the verb were repeated throughout the stimuli set. To avoid introducing an irrelevant dimension to the sort, all of the names were of the same gender. The stimuli are provided in the Appendix. Procedure. The participants were tested as a group. Each participant was given one shuffled set of stimulus cards to sort. Participants were first asked to write a paraphrase for each sentence on a blank sheet of paper to ensure that they processed the sentences, paying attention to their meaning. Once they were done writing the paraphrases, they were asked to sort the sentences into four piles, each pile containing four sentences, based on the overall meaning of the sentence, so that sentences that were thought to be closer in meaning were placed in the same pile. The instructions also said that sentences that contain roughly the same words can have very different meanings. This was illustrated with an example. It was pointed out that kick the bucket is closer in meaning to die than to kick the dog. This example was Argument Structure Constructions 12 chosen so that it would be equally biased towards a verb and a constructional sort. The example shows that the same morphological form of the verb can have different meanings, but it also illustrates that instances of the same construction can differ crucially in meaning. The idiomatic kick the bucket is an instance of a transitive construction and it is closer in meaning to die which is an instance of an intransitive construction, than to kick the dog which is again a transitive construction. We emphasized that the sentences in the experiment would not contain idioms. Results Out of the 17 participants, 7 sorted entirely by construction (41%), no participant sorted entirely by verb, and the other 10 performed mixed sorts. These results are inconsistent with the predictions of verb-centered approaches and obtained in spite of the unidimensional sorting bias. Among the participants who produced mixed sorts, 7 produced sorts that contained unequal numbers of sentences. Because of the way in which the materials were constructed, sorting in piles with unequal numbers of sentences necessarily resulted in a mixed sort. The presence of unequal piles indicates that participants were sorting as they felt was most appropriate, without using overt strategies that would yield four equal piles. In not following the instructions to sort into equal piles, participants who produced sorts with unequal piles performed somewhat of a less constrained task. In order to analyze the sorts of participants who produced mixed sorts, and to determine their overall sorting strategy, we computed a deviation score (Lassaline & Murphy, 1996) from an entirely verb-based sort and a deviation score from an entirely constructional sort. The deviation score from a verb-based sort was obtained by counting the number of changes that would have to be made for a sort to be entirely by verb (Vdev). The maximum number of changes required to produce an entirely verb- Argument Structure Constructions 13 based sort was 12. An entirely verb-based sort, then, would receive a score of 0Vdev, an entirely constructional sort would receive a score of 12Vdev. The constructional deviation score (Cdev) was computed by counting the number of changes that would have to be made for a sort to be entirely by construction. If participants sorted entirely by construction they would receive a score of 12Vdev and 0Cdev. Excluding the participants who did not follow the instructions to sort in equal piles did not change the results significantly, so they were included in our analysis. Across all participants, verb deviation scores were significantly different from 0, indicating that participants were not sorting entirely by verb (t(16) = 17.6; p < .0001). Construction deviation scores were also significantly different from 0, indicating that participants were not sorting entirely by construction either (t(16) = 3.8; p < .002). However, sorts were significantly closer to a constructional sort than to a verb-based sort. The average number of changes required for the sort to be entirely by verb (mean Vdev) was 9.8. The average number of changes required for the sort to be entirely by construction (mean Cdev) was 3.2. The Vdev score significantly exceeded the Cdev score (t(16) = 4.7; p < .0002), indicating that participants were more influenced by shared constructions than by shared verbs. We were interested in knowing whether individual verbs would be treated differently by our participants. For example, it was possible that get and take, being less semantically contentful, would be more likely to be put into separate piles than the more contentful slice and throw, it might be that people rely on the argument structure pattern to infer the meaning of the sentence only when the verb is less contentful. To test whether such verb specific differences were present in our data, we looked at the number of separate piles that each verb was placed into by each participant (verb spread). There were no differences in the average number of separate piles each verb was put into by our participants (F(3,48) < 1). None of the single degree of freedom tests contrasting the average number of piles for a single verb with the other Argument Structure Constructions 14 verbs approached significance (all Fs <1). We also tested whether there were differences among the constructions. We counted the number of separate piles that each construction was placed into by each participant (construction spread). The omnibus test was marginally significant (F (3,48) = 2.53, p= .07). The single degree of freedom test contrasting the average number of piles into which participants placed the ditransitive construction with the other constructions was significant, indicating that on average participants put the ditransitive sentences in a smaller number of piles than the other constructions (F(1,16) = 8.14, p < .01). None of the other single degree of freedom tests were significant (Fs < 1). Additional indication that the ditransitive construction was the easiest one to identify comes from the data of the participants who performed mixed sorts. Even among these participants, there were those who identified one or two constructions, that is, they grouped all the sentences that were instances of one construction into one pile. Among the mixed sorts, the number of participants that correctly identified a construction was five, three, one, and one for the ditransitive, caused- motion, transitive and resultative constructions, respectively. Among the participants who performed mixed sorts, there was only one instance of grouping together all of the four sentences which contained the same verb. The verb was ‘slice’. Discussion The results suggest that the verb-centered views that attribute the overall meaning of a sentence to the main verb cannot be entirely correct, and that indeed argument structure constructions are better predictors of overall sentence meaning than the morphological form of the verb. Participants in Experiment 1 frequently sorted entirely by construction, and never wholly by the morphological form of the verb. Averaging across all subjects, sorts were closer to a constructional sort than to a verb sort. Argument Structure Constructions 15 The results do not seem to be an artifact of the particular verbs that we chose. Take and get have particularly flexible meanings, and have sometimes been claimed to be almost contentless. However, the other two verbs, throw and slice, are clearly contentful, and there was no discernible difference in patterning between the former and the latter types of verbs. The fact that the more semantically contentful verbs did not lead to more verb-based sorts than the less contentful ones suggests that the role of argument structure in determining overall sentence meaning does not depend on the semantic content of the verb. The results are also unlikely to be an artifact of the particular constructions that were chosen. The set of four constructions involved factors that might have actually been expected to bias against a constructional sort. First, the transitive construction is very general and flexible; the associated meaning can vary widely, depending largely on the type of verb that appears in it. Second, two of our constructions were closely related: the caused-motion and resultative constructions are in fact sometimes assumed to be instances of the same construction. Our results reflect these observations: the easiest construction to identify was the ditransitive. Sorting of sentences has been shown to be sensitive to the semantic distance between the words in the sentence. Healy and Miller (1970) found that when words used as agents were semantically closer than the verbs, participants were more likely to sort along the more variable dimension (i.e., by verbs). In fact, there is indirect indication that our constructions were overall semantically closer to one another than the verbs, which should have biased participants against constructional sorts. To estimate the semantic distance among the constructions, we chose the lexical items which most closely matched the meaning of each construction: give (ditransitive), put (caused-motion), do (transitive), and make (resultative). We then compared the semantic similarity between the words matching the constructional meaning and the similarity between the meanings of the verbs used in Experiment 1. As a measure of Argument Structure Constructions 16 semantic similarity among words we used the Latent Semantic Analysis (LSA) cosines (Landauer & Dumais, 1997). Words in LSA are represented as vectors in highdimensional semantic space. Within this space it is possible to use the cosine of the angle (theta) between any two vectors as a measure of the similarity between the two corresponding words. High values of cosine theta correspond to high semantic similarity, and low values indicate low semantic similarity. LSA cosines have been shown to correlate with measures of semantic similarity obtained in a variety of cognitive tasks involving association, semantic processing, and categorization (Landauer, Foltz & Laham, 1998). The comparison between the LSA cosines for the words corresponding to the meanings of the constructions (i.e. do, make, give, put), and the cosines for the verbs used in Experiment 1 (i.e. take, throw, slice, get) shows that overall constructional meanings were significantly closer in semantic space than the meanings of the verbs. The pairwise cosines among the four verbs were computed and the pairwise cosines among the four words for the constructional meanings were computed. The mean cosine for the constructional meanings was .56 and the mean cosine for the verbs was .33 (t(11) = 2.8; p < .018). Thus, all things being equal, one would expect more verb sorts than construction sorts, since the semantics of the verbs are more highly distinguished. Because of the robustness of the unidimensional sorting bias and the fact that the constructional meanings appear to be less easy to distinguish than the verb meanings according to the LSA measure, it was somewhat surprising that so many participants in Experiment 1 sorted by construction, and none entirely by verb. Although the unidimensional sorting bias has been shown to persist despite instructions to sort stimuli by paying attention to multiple dimensions (Medin et al., 1987), it is possible that something in the instructions was highly effective in causing subjects to avoid verbbased sorts. The aspect of the instructions that may have deterred participants from verb sorts was the example that we provided, in which we showed that two sentences Argument Structure Constructions 17 with the same morphological form of the verb can mean different things. Although the same example simultaneously demonstrated that two sentences with the same construction could have different meanings, it could be that subjects were more aware of the shared verb than the shared construction, since subjects are used to identifying words and unused to explicitly identifying particular constructions. Another potential shortcoming of Experiment 1 is that verbal protocols of individual participants’ sorting strategies were not collected because participants were tested as a group. Although both our instructions and procedures were intended to make participants pay attention to the meaning of the sentences, what looks like an entirely constructional sort could have been the result of a strategy of sorting by sentence form without attention to meaning. In order to rectify these shortcomings, we conducted a second experiment testing subjects individually, with the same materials and instructions but without the example involving kick the bucket. Post-sorting verbal protocols were also gathered to better ascertain why subjects performed the sorts they did. Experiment 2 Method Participants. Seventeen University of Illinois students were paid for their participation. Stimuli. The stimuli were the same as in Experiment 1. Procedure. Participants were tested individually. The instructions were the same as in Experiment 1 except that no example was provided. Participants were asked to write paraphrases for each sentence and then to sort sentences based on overall sentence meaning. We emphasized that there was no right or wrong answer, and that we were interested in knowing how people sorted English sentences based on meaning. Argument Structure Constructions 18 When participants were done with the sorting, with the piles still in front of them, they were asked to briefly describe how they had performed the sorting and whether they had noticed any repeated words across the sentences. The experimenter took notes as accurately as possible and the notes were used to identify participants’ basis for sorting (Ahn & Medin, 1992; Medin et al., 1987). Results Sorting results Seven of the 17 participant sorted entirely by verb, six sorted entirely by construction and four performed mixed sorts. Of the mixed sorts, one contained piles with unequal numbers of sentences. Including the four participants who produced mixed sorts and analyzing their deviation scores from constructional and verb-based sorts, the data revealed that unlike Experiment 1, sorts were equally close to a constructional sort and to a verb sort. The average number of changes required for the sort to be entirely by verb (mean Vdev) was 5.5. The average number of changes required for the sort to be entirely by construction (mean Cdev) was 5.7. The Cdev score and the Vdev score were statistically indistinguishable (t(16) < 1; p = .7). The analysis of the measure of verb spread did not reveal any difference among the verbs either in the overall test (F <1) nor in any of the single degree of freedom tests (all Fs<1). The measure of construction spread also revealed no significant differences among the constructions either in the overall test or in any of the single degree of freedom tests. However, there was still some indication that the ditransitive construction was the easiest construction to identify. Among the four mixed sorts, the ditransitive was the only construction to be completely identified by two of the participants. No other construction and none of the verbs was used to form a grouping of four sentences. Although these results are consistent with the hypothesis that participants were sorting based on meaning and that constructions do contribute to meaning, an Argument Structure Constructions 19 alternative account for the constructional sorts is that participants were sensitive to surface cues of the sentences. In fact, the sentences that instantiated the different constructions varied in their length and in the number of proper names objects, prepositions, and adverbs. To address the issue we analyzed the explanations provided by the participants. Analysis of the protocols One of the written protocols corresponding to a verb sort was lost due to experimenter error. Three judges who were naive about the hypotheses tested in the experiment were asked to classify the remaining 16 protocols. The judges were not told that the participants had been instructed to sort the sentences based on meaning. All they were told was that participants had sorted sentences, and that after sorting they were asked to explain how they performed the sorting. The judges were asked to decide whether they thought that the participants sorted according to overall meaning or to considerations of sentence form, such as the length of the sentences, their complexity, the number of words, the number of proper names, the number of objects, or the number of prepositions. They were also told to note whether they thought any of the protocols was ambiguous between meaning and form. For 15 of the 16 protocols there was 100% agreement among the judges that participants had sorted based on meaning. For one of the protocols, one of the judges decided that the explanation was ambiguous between meaning and form; two of the judges decided that it was unambiguously based on meaning2. The analysis of the protocols strongly suggests that participants in Experiment 2 were paying attention to the meaning relationships among the sentences. Prior to collecting the protocols we did not have any hypotheses about the nature of the explanations that participants would provide. However, we did not expect people to be able to give the kinds of abstract definitions that linguists use to describe the meaning of the constructions. It was somewhat surprising to find among the protocols explanations that did in fact make explicit the kind of abstract relational Argument Structure Constructions 20 meaning shared by the different instantiations of a construction. The explanations provided by two of the participants (referred to as A and B) who were able to give abstract definitions consistently for the different constructions are given below. Ditransitive (X causes Y to receive Z). A: In this pile there were two people and one person was doing something for the other person. B: Here one person is doing something for another person. Transitive (X act on Y). A: In this pile a person is just doing something not very elaborate. B: Here one person is doing an action with an object. Resultative (X causes Y to become Z). A: In this group a person is doing something to an object and the object changes. B: Here a person is breaking down or putting something together. Caused motion (X causes Y to move Z). A: . .doing something with an object but specifying it more, for example here she is taking it in, where?, into the house. B: Here a person is taking an object and moving it to a different location. Discussion The results of Experiment 2 suggest that people probably see both verbs and constructions as relevant to establishing meaning. The sorting paradigm provides a stringent test for detecting whether constructions contribute to sentence meaning because the unidimensional sorting bias would favor sorts based on the shared morphological form of the verb. However, the limitation of the sorting method is that participants tend to use only one basis for sorting, even if they see two or more bases for similarity. Thus, the patterns of different subjects probably reflect the mix of factors influencing similarity within individual subjects. The fact that there were still a Argument Structure Constructions 21 considerable number of constructional sorts conflicts with the expectations of a verbcentered approach, which predicts that participants would overwhelmingly sort by the verb. In addition, all of the participants whose sorts matched a constructional sort on the surface provided verbal descriptions that indicated that the sort was a true constructional sort based on the meaning of the sentences, not just their form. Although constructions are not something that speakers are taught about or have any experience in explicitly identifying, a few of our participants who performed constructional sorts were able to provide definitions that were quite close to the ones posited by linguists for the abstract meanings of the different constructions. General Discussion The two experiments reported here suggest that the traditional view that the verb is the main determinant of the syntax and semantics of sentences, cannot be entirely right. The alternative view, that argument structure constructions are directly associated with sentence meaning, is supported by the fact that an overwhelming number of participants in Experiment 1, and 6 out of 17 participants in Experiment 2, sorted the sentences by construction. Constructional sorts were obtained in spite of the fact that the stimuli contained a visible shared dimension (the same morphological form of the verb) which allowed for easy unidimensional sorting, and in spite of the fact that the meanings of the constructions were more similar than the meanings of the verbs, as determined by the LSA measure. The fact that a substantial number of constructional sorts were performed is also striking in light of a methodological aspect of the unidimensional bias in sorting experiments outlined earlier. In both of our experiments, participants had all the stimulus sentences available for scrutiny at all times. This type of procedure has been found to induce more unidimensional sorts, a procedure in which people compare each item to an already categorized standard provided by the experimenter (Regehr & Brooks, 1995). Regehr and Brooks (1995) suggested that when all the stimuli are present for viewing at the same time, participants scan the whole Argument Structure Constructions 22 array looking for a simple general principle on which to form categories. Given the findings in the categorization literature, the presence of constructional sorts indicates that constructional meaning plays a critical role in sentence interpretation. The present study does not distinguish between a constructional approach and the multiple-senses approach in that it does not rule out the possibility that the same morphological form of the verb was understood to correspond to four different verb senses. On that view, the reason that instances of throw, for example, were put into separate piles was because each instance represented a distinct sense which was more similar in meaning to one of the senses of another verb than to the other senses of throw. However, the only way for subjects to discern which verb sense was involved was to recognize the argument structure pattern and its associated meaning. That is, the proposed different verb senses all look the same; the only way to determine that a particular sense is involved is to note of the particular argument structure pattern that is expressed and infer which verb sense must have produced such a pattern. Therefore, at least from a comprehension point of view, the pairing of argument structure pattern with meaning must be primary. The multiple sense approach to argument structure may run into problems that are avoided by the constructional approach, however (Goldberg,1995). As an example, consider the sentences in (4): (4) a. She sneezed the foam off the cappuccino. b. The truck rumbled down the road. c. She baked him a cake. To account for the fact that speakers of English are able to understand sentence 4a, the multiple-sense approach would require positing for sneeze, which we normally think of as an intransitive verb, a sense which requires three arguments and has the Argument Structure Constructions 23 meaning “X causes Y to move (to/from) Z by sneezing”. For rumble, a verb of sound emission, the multiple-verb-sense view would have to assume the existence of a verb sense meaning “X moves Y while rumbling”; finally for bake it would require a sense roughly corresponding to “X intends Y to receive Z by baking.” In a constructional approach, the stipulation of these implausible verb senses is avoided by recognizing that the phrasal pattern itself is associated with the meanings of caused motion, intransitive motion and transfer, respectively. The constructional meaning integrates with the more specific verb meaning in particular ways. Sneezing causes the transfer; rumbling is an effect of the motion; and baking is a precondition of transfer (see Goldberg, 1997, for discussion of the ways verb meaning and construction meaning can be related). In light of such cases, early proponents of the multiple-verb-sense approach have recognized certain instances in which it seems preferable to view verb meaning as composing with an independently existing construction or template (Rappaport Hovav & Levin, 1998). The most important contribution of this study is that it provides a sufficiency proof that types of complement configurations play a crucial role in sentence interpretation, independent of the contribution of the main verb. The results suggest that constructions are psychologically real linguistic categories that speakers use in comprehension. Argument Structure Constructions 24 References Ahn, W., & Medin, D. (1992). A two-stage model of category construction. Cognitive Science, 16, 81-121. Anderson, S. R. (1971). On the role of deep structure in semantic interpretation. Foundations of Language, 6, 197-219. Boland, J. E., & Boehm-Jernigan, H. (1998). Lexical constraints and prepositional phrase attachment. Journal of Memory and Language, 39, 684-719. Borkin, A. (1974). Problems in form and function. Norwood, NJ: Ablex. Chomsky, N. (1965). Aspects of the theory of syntax. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. Chomsky, N. (1982). Some concepts and consequences of the theory of Government and Binding. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. Fillmore, C., & Kay, P. (1999). Regularity and idiomaticity in grammatical constructions: the case of Let Alone. Language, 64, 501-538. Fillmore, C. J. (1968). The case for Case. In E. Bach & R. T. Harms (Eds.), Universals in Linguistic Theory (pp. 1-88). New York, NY: Holt, Rinehart and Winston. Garnsey, S. M., Pearlmutter, N. J., Myers, E., & Lotocky, M. A. (1997). The contributions of verb bias and plausibility to the comprehension of temporarily ambiguous sentences. Journal of Memory and Language, 37, 58-93. Goldberg, A. (1995). Constructions: A construction grammar approach to argument structure. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. Goldberg, A. (1997). Relationships between verb and construction. In M. Verspoor & E. Sweetser (Eds.), Lexicon and Grammar (pp. 383-398). Amsterdam: John Benjamins. Green, G. (1974). Semantics and syntactic regularity. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press. Healy, A., & Miller, G. (1970). The verb as the main determinant of sentence meaning. Psychonomic Science, 20, 372. Argument Structure Constructions 25 Jackendoff, R. (1997). Twistin' the night away. Language, 73, 534-559. Juliano, C., & Tanenhaus, M. (1994). A constraint based lexicalist account of the subject/object attachment preference. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research, 23, 459-471. Katz, J., & Postal, P. (1964). An integrated theory of linguistic descriptions. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. Landauer, T., & Dumais, S. (1997). A solution to Plato's problem: The latent semantic analysis theory of acquisition, induction, and representation of knowledge. Psychological Review, 104, 211-240. Landauer, T., Foltz, P. W., & Laham, D. (1998). An introduction to latent semantic analysis. Discourse Processes, 25, 259-284. Larson, R. K. (1988). On the double-object construction. Linguistic Inquiry, 19, 335-391. Lassaline, M., & Murphy, G. (1996). Induction and category coherence. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 3, 95-99. Levelt, W. (1989). Speaking: From intention to articulation. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. Levelt, W., Roelofs, A., & Meyer, A. (1999). A theory of lexical access in speech production. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 22, 1-75. Levin, B., & Rappaport Hovav, M. (1995). Unaccusativity at the syntax-lexical semantics interface. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. MacDonald, M. C., Pearlmutter, N. J., & Seidenberg, M. S. (1994). Lexical nature of syntactic ambiguity resolution. Psychological Review, 101, 676-703. Medin, D. L., Wattenmaker, W. D., & Hampson, S. E. (1987). Family resemblance, conceptual cohesiveness, and category construction. Cognitive Psychology, 19, 242-279. Michaelis, L., & Lambrecht, K. (1996). Toward a construction-based theory of language function: The case of nominal extraposition. Language, 72, 215-247. Partee, B. H. (1965). Subject and object in Modern English. New York: Garland. Argument Structure Constructions 26 Pickering, M. J., & Branigan, H. P. (1998). The representation of verbs: Evidence from syntactic priming in language production. Journal of Memory and Language, 39, 633-651. Pinker, S. (1989). Learnability and cognition: The acquisition of argument structure. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. Rappaport Hovav, M., & Levin, B. (1998). Building verb meanings. In M. Butt & W. Geuder (Eds.), The projection of arguments: Lexical and compositional factors (pp. 97-134). Stanford, CA: CSLI Publications. Regehr, G., & Brooks, L. R. (1995). Category organization in free classification: The organizing effects of an array of stimuli. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 21, 347-363. Rosch, E., & Mervis, C. B. (1975). Family resemblance: Studies in the internal structure of categories. Cognitive Psychology, 7, 573-605. Smith, L. B. (1981). Importance of overall similarity of objects for adults' and children’s classifications. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 1, 811-824. Trueswell, J. C., Tanenhaus, M. K., & Kello, C. (1993). Verb specific constraints in sentence processing: Separating effects of lexical preference from garden-paths. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, & Cognition, 19, 528-553. Wierzbicka, A. (1988). The semantics of grammar. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. Argument Structure Constructions 27 Appendix A Sentences used in Experiments 1 and 2 Construction Verb throw transitive Anita threw the hammer get Michelle got the book slice Barbara sliced the bread. take Audrey took the watch. ditransitive Chris threw Linda the pencil. Beth got Liz an invitation. Jennifer sliced Terry an apple Paula took Sue a message. caused motion Pat threw the keys onto the roof. Laura got the ball into the net. Meg sliced the ham onto the plate. Kim took the rose into the house resultative Lyn threw the box apart. Dana got the mattress inflated Nancy sliced the tire open Rachel took the wall down. Argument Structure Constructions 28 Footnotes 1 Because all (English) sentences require a subject argument, following Chomsky (1982), many linguistic theories have simplified the subcategorization information so that it only includes non-subject arguments. 2The sorting strategy associated with this protocol was entirely by construction. The explanation provided in the protocol was the only one that mentioned both an element of form “the sentence structures -here you have two names” and meaning “when you paraphrase the meaning looks more similar.” Argument Structure Constructions 29 Authors’ Notes Giulia M. L. Bencini, Adele E. Goldberg Department of Linguistics, University of Illinois, Urbana, IL 616801. The research reported here was supported by NSF Grant SBR-9873450 to the second author. Portions of this work were reported at the 21st Annual Conference of the Cognitive Science Society in Vancouver in August, 1999. The authors thank Alice Healy, Laura Michaelis, Gregory Murphy, Alberto Nocentini , Bob Rehder, and an anonymous reviewer for helpful comments on this project and I-Chiant Chiang, Malcolm MacIver and Linda May for their assistance in classifying the protocols for Experiment 2. Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Giulia Bencini, Beckman Institute for Advanced Science and Technology, 405 North Mathews, University of Illinois, Urbana, IL 61801. Argument Structure Constructions 30 Table 1: English Argument Structure Constructions Construction Form Meaning Example Transitive Subject Verb Object X act on Y Pat opened the door Ditransitive Subject Verb Object1 Object2 X causes Y to receive Z Sue gave her a pen Resultative Subject Verb Object Complement X causes Y to become Z Kim made him mad Caused motion Subject: Verb Object Oblique X causes Y to move Z Joe put the cat on the mat