Microsoft Word - UWE Research Repository

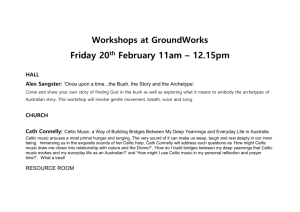

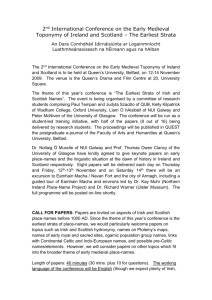

advertisement