Modeling Potential Adoption of Medicinal Plant Cultivation in

advertisement

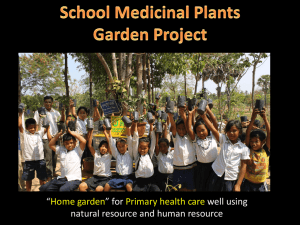

1 Modeling Potential Adoption of Medicinal Plant Cultivation in Paraguay Using Ethnographic Linear Programming Norman Breuer Abstract Limited-resource farmers in Eastern Paraguay moved from traditional farming systems toward cotton solecropping during the 1970s and 1980s. Toward the end of this period, cotton prices crashed and farmers were left with few sources of income. Cultivation and marketing of medicinal plants may be a source of supplementary income for certain households. Markets exist, as medicinal plant consumption is widespread. Surveys and interviews were conducted during fieldwork at two sites in 1999. Ethnographic linear program models were constructed to describe and analyze the farming systems. The principal conclusion reached through testing several scenarios was that the recommendation domain for medicinal plant cultivation projects is households with abundant female labor located within an eight-hour roundtrip from the main market. Keywords Paraguay, Ethnographic Linear Programming, Medicinal Plants, Gender, Household Composition. Introduction Paraguay is a landlocked country in the heart of South America, with an area of 406,752 sq. km. It is bisected by the Tropic of Capricorn, and has a continental subtropical and tropical humid climate. The current population is estimated to be 5,050,000. Population growth rate of 3.2% is among the highest in South America. If this trend continues, the population will double in 22 years. Population is 50.3% urban and 49.7% in rural and by the year 2010, Paraguay will be an urban country. Nevertheless, the rural population will grow by 570,000 persons or 100,000 families by then. With 37% actively engaged in agriculture, rural Paraguay will continue to be important and strategic in any process of economic growth. As in many developing nations, 67% are under 30 years of age and 41% are less than 15 years old (Palau, 1998). Small farmers known as “campesinos” in Paraguay were drawn closer to the consumer or market economy during the 20 years in which a system of solecropping of cotton was in place (1970-1990). Relatively high and stable price of cotton allowed mills and middlemen to advance campesinos money based on the amount of land they would be planting in cotton. Perhaps for the first time, consumer products were readily available to small farmers. Cotton prices crashed in the late 1980s (Palau, 1998; Gutiérrez, 1995; Ocampos, 1994). More than a decade later, many households are living on the interface between the subsistence and market economies. Aggressive advertisement campaigns for soft drinks and clothing as well as tastes acquired during the cotton “boom” draw people toward the consumer side. However, a renewed awareness of the importance of food security, government campaigns for a return to diversified agriculture, and the simple lack of cash 2 steer people back toward the perceived safety of the subsistence economy. Adoptable, low-input technologies may help households acquire discretionary cash above subsistence needs. Objective and Research Questions The study was designed to explore new sources of supplementary income for resourcelimited farm households. Testing the feasibility of adoption of medicinal plants as a cash crop for income was the main objective. Other objectives were also examined, including food security, home healthcare security and discretionary cash income. Effects of land holding size and remittances received were also studied. This study was originally guided by three research questions 1) What type of household can grow medicinal plants as an alternative cash crop? 2) How does distance from markets affect the mix of crops and medicinals that farmers grow and can sell? 3) Are households better off if they combine market and non-market strategies because they can better maintain food and health security? We hypothesized that households with certain age and gender compositions, located closer to markets would be more likely to adopt and benefit from a new activity of growing medicinal plants for extra income. Furthermore, we hypothesized that these types of households could be identified using ethnographic linear programming techniques (Kaya 2000; Bastidas, 2001.) Study Sites This study focused on two communities. The first Aguaity, Eusebio Ayala has a population of around 600, which has remained relatively stable due to high rates of migration. It is one of the earliest colonized regions of Paraguay and most soils are exhausted from up to 400 years of continuous use, which along with its hilly topography, explain in great measure the state of extreme deterioration of all natural resources today, which has been compounded by several decades of cotton solecropping (Fretes et al., 1993.) Another characteristic of this region is its division into very small plots or “minifundios,” a great number of which are less than one hectare in size, and have poor to very poor soil. Average farm size was just over four hectares. These farmers were compared to farmers in a more remote region, Ñu Pyahú, in the Department of Caazapá. This is an older established “compañía” or outlying district of San Juan Nepomuceno. There were no community development or other projects underway at the time the study was undertaken. Ñu Pyahú is a small hamlet of some 70 homes, with a population of around 450 people. San Juan itself is a small town, yet large enough to provide a very limited market for the selling and purchase of goods. Its mean annual rainfall is around 1500 mm. Soils are similar to those in Aguaity, but with less rocky outcroppings. Average farm size was 13.22 ha. Agricultural production in both areas involves a range of traditional crops (maize, manioc, cotton, tobacco, peanuts, squash, field peas, etc.) along with some recently introduced ones (tomatoes, hybrid mangoes.) While Eusebio Ayala farmers tend to have more fruit trees, and fewer subsistence crops, those in Ñu Pyahú have more subsistence crops along with complimentary agricultural and homemade crafts (Fretes et al., 1993; 3 Ocampos, 1994; Poey, 1986). The livelihood system often includes yerba mate (Ilex paraguariensis) processing, blanket weaving, and cane syrup home manufacture, as well as making “torcido,” or chewing tobacco ropes and other activities. At both sites a few farmers had a general store in front of the house for self-consumption and to bring in some cash. There are many differences as well as similarities between the sites. However, the similarities outweigh the differences, suggesting that farmers at both sites face many similar constraints, and count on similar resources. Principal differences between the farming systems at Eusebio Ayala and Ñu Pyahú are less land available to farmers at Eusebio Ayala, and less access to market for those at Ñu Pyahú. In the latter case, this leads to lower prices for farm products and higher prices for purchased items. Otherwise, in the linear programs used here, both sites are considered parts of one general livelihood system. Methods and Fieldwork Interviews: Five households expected to have a variety of family compositions were interviewed at each site to obtain information on farming systems for modeling. Another 45 families were surveyed between both sites seeking data on medicinal plant use. Qualitative data was gathered through open-ended questionnaires and conversations. The principal male and/or female member of each family was surveyed with specific questions about who cares for the home garden and the “chacra” or field. Additional questions sought data on time allocation for each activity, and how plants are used when illness strikes. Community members of different ages, sex and social standing reported on roles as producers, collectors and users of medicinal plants through narratives. These data served as descriptors focused on identifying the illnesses that occur most frequently in the household, including injuries, and the preventative measures or first-aid response to these afflictions and how people manage them. Stories brought out how deeply ingrained the use of medicinal plants is in Paraguayan culture. Most interviews were conducted in the Guaraní language. Having a mixed gender team, perceived as more serious and less intimidating, facilitated rapport with women. Quantitatively, five households at each site were analyzed using linear programming as it applies to economic analysis of small farm livelihood systems. In this manner, several families in different stages of their life cycles were studied in search of diversity rather than attempting to identify a “typical” household (Hildebrand, 1986). The main activities and constraints were identified and quantified during family interviews. A model was created in which men’s, women’s, adolescent and children’s contributions to the family economy were disaggregated and quantified, especially with regard to the home medicinal plant garden and its use. Economic Analysis Using Ethnographic Linear Programming Household differences were brought out in the different scenarios tested to show the diversity of livelihood strategies within this general system as they respond to differing household socioeconomic conditions. These were expected to lead to or help identify recommendation domains for the cultivation and sale of medicinal plants. Most information for the models was gathered through the several methods of anthropological 4 research. Thus the models are referred to as Ethnographic Linear Programs (ELPs.) We follow Bernard (1995) using ethnography as an active process of interacting with the clientele –in this case the farmers—to gather information. Pre-testing the adoption likelihood of new technologies may save money and time for limited-resource agriculture ministries in developing countries by providing a head start towards specific domains to be targeted. ELP work is site and time-specific, ethnographic and participatory. The specific ELP methodology used in this paper involved the use of an Excel® spreadsheet. Activities including crops raised for consumption and sale, a medicinal herb garden, selling activities, remittances, a grocery buying activity (including meat) and cash transfers were columns. Rows were resources and constraints on the system and these included land, labor, consumption of various crops and other food, accounting rows and beginning cash for each quarter of the year. The objective function was the maximization of discretionary end-year cash after food requirements were met. The term “End Year Cash” refers to the amount of money left over, after expenses are paid, for discretionary spending, or the purchase of “luxuries.” That is, things not strictly needed for survival. Medicinal Plants1 The technology tested was the production of medicinal plants, a specialty crop. Medicinal plants refers to one or many species known as herbs, medicinals or botanicals in a variety of admixtures to be sold as unprocessed leaves, flowers, stems, roots, tubers, rhizomes, barks, gums, resins or seed. There are many species in demand on the Paraguayan market (Basualdo, 1995; Didier et al., 1999.) A farmer therefore might be better off by offering a range of them.2 There is an internal market in Paraguay for medicinal plants of between 12 to 30 million dollars per annum3. “Medicinal plants” refers here to the growing of several species in a home garden context. The fact that the crop consists of several species does not detract from it being considered one specialty crop. Model Calibration The baseline ELP was calibrated in the following manner. Once the model was running with all the known factors in place, coefficients that we questioned were tested iteratively until areas devoted to each type of crop or activity resembled a known farm. Using induction, yield was looked at specifically as a source of error in modeling. In effect, the use of research station or government statistic yields led to constant errors in the amount of land farmed. By halving government reported yields, then halving them again, a real picture of a farm was drawn. One result evident from this is that farmers plan on low yields and my take anything above and beyond their estimates as windfall. 1 Medicinal plants refers to one or many species known as herbs, medicinals or botanicals in a variety of admixtures to be sold as unprocessed leaves, flowers, stems, roots, tubers, rhizomes, barks, gums, resins or seed. 2 Mrs. Arza of Aguaity reported that producing only one species was very risky and that she always takes a variety basket to market. 3 No data are available. Values were calculated from market visits and mean intake of interviewees. 5 Results A. Household Composition and Potential Adoption: Both household composition and distance to market were used as variables to identify potential adopters. Distance to market was captured in the “sell medicinal plant” activity of the ELP matrix. Table 1. Household Compositions Tested A Family 1 Adult Male 1 Adult Female 0 Teen girls 0 Children< 12 B 1 1 0 3 C 1 1 2 3 At Aguaity, Eusebio Ayala, 80 km from the main market, three family compositions were tested to see their response as possible target households for medicinal plant cultivation extension projects. Household of type A cultivated 0.012 ha of medicinal plants. Households of type B cultivated no medicinal plants. Household of type C cultivated 0.012 ha. of medicinal plants, the same amount as Household A. At Ñu Pyahú, 250 km from the main market, the same family compositions were tested. Families A and B did not grow medicinal plants. Household C grew a very small plot (6 m2). It can be concluded that no family this far from the market should be targeted as potential medicinal plant producers under current conditions. Figure 1. Medicinal Plant Production by Households at Aguaity, Eusebio Ayala and Ñu Pyahú Medicinal Plants Cultivated at the Study Sites for Three Household Compositions 140 Square Meters 120 100 80 Ñu Pyahú 60 Aguaity 40 20 0 A B C Household Types B. Effects of Distance to Markets Figure 2. Effects of Distance to Market on Size of Garden and Units Sold 6 Bags sold 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 Sq. meters Bags 3 3. 5 4. 8 6 6. 5 7 8 10 350 300 250 200 150 100 50 0 2. 5 Square meters Effect of Distance to Market on Size of Medicinal Plant Garden and Units Sold Round Trip Hours Distance to market was incorporated into the ELP matrix as a column for selling medicinal plants. Time to and back from market was increased over several iterations. Results show that an eight-hour round trip is the cut-off point for medicinal plant sales. Both area planted to medicinals and number of bags sold are highest within a one-hour journey to the market, and drop to zero above the eight-hour level. C. Distance and Number of Crops Grown Site Table 2. Distance and Crop Mix Distance from Average ASU (Km) Farm size Cultivated Species Gathered Species 80 4 ha 37 49 Aguaity 250 13 ha 28 21 Ñu Pyahú Source: Surveys conducted with Paraguayan farmers in Jul.-Aug. 1999. Other Crops 8 17 At Eusebio Ayala, the site nearer to Asunción, only nine crops were grown (medicinals were considered as one crop.) At Ñu Pyahú on the other hand, farmers grew 17 different crops. At Eusebio Ayala, interviewees mentioned a total of 86 species. Of these, 37 were cultivated and 49 gathered. At Ñu Pyahú, 250 km from the main market, only 49 species were mentioned altogether of which 28 were cultivated and 21 gathered. Production and gathering of many varieties within one crop may be augmented through contact with the market. Women have been marketing medicinal plants for generations. They normally receive inputs from other vendors and requests from clients for different varieties. These include local species as well as heretofore-unknown foreign species and varieties which small farmers manage to obtain and produce. The market is in this sense both a driver of specialization and a source of information for additional cash crops that leads to a more diverse species composition within one specialty crop. D. Remittances and Food Security Varying amounts of reported remittances from family members were used to determine the effect on the overall functioning of the modeled households. Remittances improved the amount of cash available at the end of the year for discretionary spending. However, even at the level of zero remittances, the amount of discretionary cash was only reduced 7 by around 20 %. End-year cash does not vary when remittances are received in different quarters. The results demonstrate that the system does not rely on remittances to function. The farmer most likely considers them a windfall. E. Healthcare Shocks and Seasonality Farmers at the site nearer Asunción spent less than half compared to those at the more distant site on healthcare (Gs. 192,500 vs. Gs. 322,000.) Those nearer to the market are “better off,” in the sense that they need to spend less money at hospitals, health centers, pharmacies, doctors’ offices and local healers than those further away do. However, increased expenditures on healthcare in the first and second quarter can affect the outcome at both sites to the point of not being able to meet required minimum cash or food amounts. Shocks or unforeseen healthcare costs were introduced into each one of the quarters of the production calendar in the ELP model. Incidental costs due to illness are felt most in the first and second quarter. This is due to the fact that money from sales of the major harvest crops comes in during the beginning of the third quarter and lasts through the fourth. Conclusions Gender and Potential Adoption There were two main variables considered in determining which households would most likely benefit from the commercial cultivation of medicinal plants. These were household composition and distance from market. Survey results indicate that youngsters learn about medicinal plants principally from women but also from men. However, women traditionally gather, grow, and especially market, medicinal plants. A maleheaded household is likely to adopt the production of medicinal plants if the woman has no small children to care for and therefore has the time available for selling plants at the market. Male-headed households in which the wife has small children are only likely to adopt this technology if adolescent female labor is available. As childcare and medicinal plant sales are fungible labor activities among females of different age groups, this type of family composition provides a feasible result. Mothers can either take care of children or sell medicinal plants. Adolescent females can also sell medicinal plants and/or care for siblings. Female-headed households, the most constrained as far as labor is concerned, can only adopt this technology if there are no small children to care for, or if female adolescents are present so as to be able to share and trade the work of childcare and marketing. The most pertinent recommendations to government or non-government agencies planning to set up medicinal plant projects are the following: 1) Only households located within eight hours round-trip to markets can engage in growing and selling fresh raw medicinal plants, as they have to be taken to market on a daily basis; 2) Medicinal plants sales is an activity that falls mostly within the domain of women. Therefore, families with no principal female and no teenaged females should not be targeted; 3) If there are teenage girls and small children, the household can still engage in this activity, as the activity of caring for small children is fungible between mothers and teenage girls; 4) Households with no teenage girls but with small children should not 8 be targeted. The eight-hour trip to market and back only becomes feasible when children become adolescents or if a member of the extended family is available to care for small children; 5) At the site further from Asunción, different household compositions choose subsistent crops rather than medicinal plants, except for a very small sale from families of type C. This is due to a marketing constraint rather than household composition. References Bastidas, Elena P. 2001. Assessing potential response to changes in the livelihood system of diverse, limited-resource farm households in Carchi, Ecuador : modeling livelihood strategies using participatory methods and linear programming. Thesis (Ph.D.). University of Florida, Gainesville. Basualdo, Isabel. 1995. Medicinal Plants of Paraguay. Economic Botany: 49(4) Bernard, H. Russell. 1995. Research Methods in Anthropology. 2nd Ed., Altamira Press, Wulnut Creek, California. Didier, R., Pinazzo, J., Acevedo, C., Gonzalez, G. and Yegros, O. 1999. Etnobotánica Paraguaya, Inventario Formalizado , Etnobotánico y Socioeconómico de las Plantas Medicinales Comercializadas en los Mercados de Asunción, Paraguay. (CJBG) – Chambessy, Suiza Fretes, A. Kohler, A., and De Zutter, P. 1993. De la Organización Campesina al Desarrollo Rural Sostenible. DGP/MAG-GTZ, Asunción, Paraguay. Gutiérrez, Alejandro A. 1998. Paraguay: Sector Agrícola y Agroindustrial. Secretaría Técnica de Planificación. Hildebrand, Peter E. 1986. Perspectives on Farming Systems Research and Extension. Ed. By Peter E. Hildebrand, Lynne Rienner Publishers, Boulder, Colorado. Hildebrand, Peter E. and Luna, Edgar G. 1973. Unforeseen Consequences of Introducing New Technologies in Traditional Agriculture. In: Perspectives on Farming Systems Research and Extension. Ed. Peter E. Hildebrand, Lynne Rienner Publishers, Boulder, Colorado, 1986. Kaya, B. Hildebrand P.E. and Nair, P.K. 2000. Modeling changes in farming systems with adoption of improved fallows in Southern Mali. Agricultural Systems 66. Ocampos, Genoveva. 1994. Mujeres Campesinas y Estrategias de Vida. RP Ediciones – BASE ECTA, Asunción, Paraguay. Palau, Tomás. 1998. La Agricultura Paraguaya al Promediar la Década de 1990: Situación, Conflictos y Perspectivas. En: Las Agriculturas del Mercosur. Giarraca, N. y Cloquell, S. (comp.). Ed. La Colmena – CLACSO, Buenos Aires. Poey, Federico. 1986. Anatomy of On-Farm Trials: A Case Study from Paraguay. FSSP Training Material Series N° 603, IFAS, Gainesville.