The invasion of the termites

advertisement

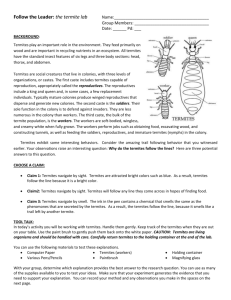

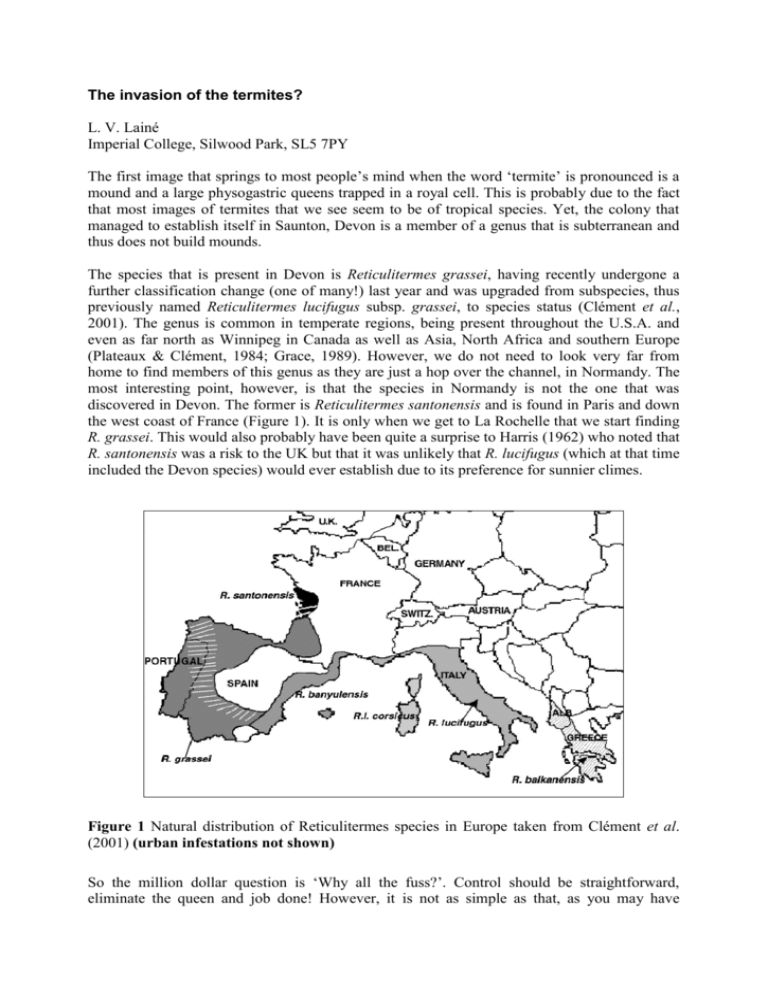

The invasion of the termites? L. V. Lainé Imperial College, Silwood Park, SL5 7PY The first image that springs to most people’s mind when the word ‘termite’ is pronounced is a mound and a large physogastric queens trapped in a royal cell. This is probably due to the fact that most images of termites that we see seem to be of tropical species. Yet, the colony that managed to establish itself in Saunton, Devon is a member of a genus that is subterranean and thus does not build mounds. The species that is present in Devon is Reticulitermes grassei, having recently undergone a further classification change (one of many!) last year and was upgraded from subspecies, thus previously named Reticulitermes lucifugus subsp. grassei, to species status (Clément et al., 2001). The genus is common in temperate regions, being present throughout the U.S.A. and even as far north as Winnipeg in Canada as well as Asia, North Africa and southern Europe (Plateaux & Clément, 1984; Grace, 1989). However, we do not need to look very far from home to find members of this genus as they are just a hop over the channel, in Normandy. The most interesting point, however, is that the species in Normandy is not the one that was discovered in Devon. The former is Reticulitermes santonensis and is found in Paris and down the west coast of France (Figure 1). It is only when we get to La Rochelle that we start finding R. grassei. This would also probably have been quite a surprise to Harris (1962) who noted that R. santonensis was a risk to the UK but that it was unlikely that R. lucifugus (which at that time included the Devon species) would ever establish due to its preference for sunnier climes. Figure 1 Natural distribution of Reticulitermes species in Europe taken from Clément et al. (2001) (urban infestations not shown) So the million dollar question is ‘Why all the fuss?’. Control should be straightforward, eliminate the queen and job done! However, it is not as simple as that, as you may have realised when I alluded to it earlier. The biology of the genus is extremely complex and termitologists themselves have a hard time agreeing on it. This task is made even more difficult when the most recent detailed work on this problem dates back to the 50’s (Buchli, 1958) and at that time classification within the genus left a lot to be desired. A further problem, that some researchers believe that species within the genus may have different reproductive strategies (Thorne, 1998), makes the whole thing a complete nightmare. alate nymph neotenic egg larva worker neotenic soldier Figure 2 Simple diagrammatic representation of Reticulitermes life cycle A brief explanation of the life cycle (Figure 2) may help to clarify the difficulties involved in control of these termites. There is a split after the larval stages into two lines, the sexual and the worker line. Individuals going down the sexual line develop into nymphs and then into either alates (which are the reproductive form most people are familiar with) or supplementary reproductives (also termed neotenics). The alates do form physogastrics, however, these are much more mobile than those found in tropical species. The alternative line of development, the neutral line, is the development of larvae into workers, these in turn can either remain as workers or develop into neotenics or soldiers. Figure 3 shows a worker and some nymphs. Workers are approximately 4 to 6 mm in length. Worker Nymph Figure 3 Picture of Reticulitermes grassei workers and nymphs Note, however, that sexual reproductives are formed from both lines. This is where the problem of control of these termites comes in as it means that theoretically any group of individuals could potentially form a viable colony. Not only that, but supplementary reproductives can be produced in very large numbers and what they lose in being less fecund than primary reproductives (or physogastrics) they gain in numbers. Going back to Saunton, the first time termites were said to be present was in 1994 (Verkerk & Bravery, 2001). There have been various theories as to where they originated from but trying to find the exact source may be rather difficult as approximately 30 years elapsed before their discovery (Verkerk, 1998). The eradication programme that was put in place (and still is running) was thoroughly explained in Verkerk et al. (2001). The latest news as to the situation in Devon was mentioned at Parliament (20 Mar 2000 : Column WA14) where it was said that there was very little activity seen and that the feeling was of 'cautious optimism' (a big sigh of relief all round). However, there is still the small problem of the fact that they somehow managed to establish and do quite well. Who is to say that they aren’t elsewhere in the UK, waiting to be discovered? Well, the simple answer is we just don’t know. I am in the process of completing a PhD, which had for aim to gain further knowledge of the various requirements of this species for colony establishment. This meant looking at minimum termite number for establishment, food preferences, soil preferences and effect of temperature on survival. The project was in no way all encompassing and many more years of research are required. However, hopefully this will be a start to trying to answer these pertinent questions. The situation in the UK, and this is true world-wide, is that we are in the midst of global warming (Hulme & Jenkins, 1998). This means that our climate is becoming favourable to more species of pest, not just termites. However, though global warming is a factor, there is a more important one and that is central heating. Over the last few decades, central heating has become so prevalent that it is now found in 92% of all households (Office for National Statistics). This is a problem that has been stated in France as far back as 1955 (Jacquiot, 1955). So what does this mean? Should we all rush to shut down our central heating and pledge to live in a more rustic (and cold!) way. Possibly the more sane response would be that there are maybe easier ways. However, if we consider that termites are present in Normandy, which has a climate rather similar to that found in the South of England, there is no valid reason for the termites not establishing themselves in more areas. There is more and more travel between the UK and France and this means that the likelihood of accidentally importing termites is getting higher and higher. Probably the most sensible solution is to be more aware that these insects may potentially be a problem and be au fait with what to look for and thus have more stringent checks at ports of entry. It is still difficult for termites to establish themselves in the UK as the climate is not ideal and though the damage that they cause can sometimes be catastrophic, it takes several years to attain these population levels. Termites are very sensitive and working in the laboratory it is evident that once isolated from a colony the rate of survival can be quite low. They are reliant on ideal moisture and temperature conditions. So, as for the answer to the title of this article, well, perhaps not quite yet! References Buchli, H. (1958) L'origine des castes et les potentialités ontogéniques des termites Européens du genre Reticulitermes Holmgren. Annales Science Naturelle, Zoologique 20, 261-429. Clément, J.-L., A. G. Bagnère, P. Uva, L. Wilfert, A. Quintana, J. Reinhard & S. Dronnet. (2001) Biosystematics of Reticulitermes termites in Europe: morphology, chemical and molecular data. Insectes Sociaux 48, 202-215. Grace, J. K. (1989) Northern subterranean termites. Pest Management 8, 14-16. Harris, W. V. (1962) Termites in Europe. New Scientist, 614-617. Hulme, M. & G. I. Jenkins. (1998) Climate change scenarios for the United Kingdom: scientific report, pp. 80. Climatic Research Unit, Norwich. Jacquiot, C. (1955) Les Colonies Parisiennes du Termite de Saintonge. La Revue du Bois 10, 15-17. Plateaux, L. & J.-L. Clément. (1984) La spéciation récente des termites Reticulitermes du complex lucifugus. Revue de la Faculté de Science de Tunis 3, 179-206. Thorne, B. L. (1998) Part I. Biology of subterranean termites of the genus Reticulitermes. pp. 1-30 NPCA Research Report on Subterranean Termites. Viginia, National Pest Control Association. Verkerk, R. & A. F. Bravery. (2001) The UK termite eradication programme: Justification and implementation. Sociobiology 37, 351-360. Verkerk, R. H. J. (1998) Termites and Building: assessing the problem from a non-comercial viewpoint. in Proceedings of the 1998 Annual Convention of the British Wood Preservation and Damp-Proofing Association, London, BWPDA. Web site: http://www.bio.ic.ac.uk/research/djwright/laine.htm E-mail: l.laine@ic.ac.uk E-mail after October 2002: lvlaine@hotmail.com