link to lecture 6

advertisement

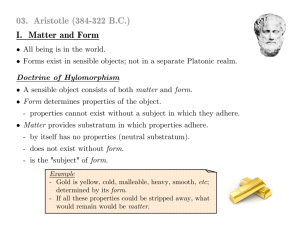

HON 280 -- LECTURE SIX (ARISTOTLE) THE DEVELOPMENT OF SCIENCE Aristotle (384 BCE). From Macedon in the North. Teacher of Alexander the Great. I. How was he different from Plato with regards to the existence of the Forms. 1. Forms do not exist outside their instances. And they are really nothing more than the defining natures of these objects, or their inner structures. A. At one point, Aristotle dealt with the example of Socrates' snub nose. He claims, the snubness of the nose is not a general property which exists independently of the nose in which other noses may participate. It is merely an aspect of Socrates' nose which only exists in its instances. II. Consequences of this difference. A. Aristotle didn't think that empirical reality was somehow unreal, and thus paid much more attention to its details. B. When he tried to account for the natures of natural things, he didn't appeal to divine plans or purposes. He did not posit a demiurge. Rather, for him, the behavior of a thing is determined by its internal nature. 1 C. Aristotle characterized the natures of natural objects in terms of various new kinds of distinctions he invented out of whole cloth for the occasion. (a) Four different kinds of explanations, or causes (or becauses) (examples on p. 12 of Gregory text). (i) Material Cause (ii) Formal Cause (iii) Efficient Cause (iv) Final Cause (b) To describe the course of an object over its lifetime is to describe its transition from potentiality to actuality. III. How are these categories used to described the growth and development of a natural object? Consider the growth of an acorn into an oak tree. A. The material cause of the oak tree is the wood out of which it is composed. B. The Formal cause of the oak tree is the inbuilt features of its defining structural organization (today we might say its DNA) C. The efficient cause of the oak tree is the other two oak trees who publicly mated (as trees are prone to do) to create the acorn from which it grew. 2 D. The final cause of the oak tree is the end state toward which oak tree growth and development tends, to become a healthy and mature member of its kind. E. There is, moreover, a special relation between the tree's final and formal cause: Its formal cause is best understood as an indwelling of its final cause. This is to say that it part of the defining structural nature of the oak tree to grow and develop into a healthy and mature member of its kind. F. Also, as the formal cause operates, the organism changes from acorn to oak tree, finally realizing its final cause. It goes from being potentially an oak tree to becoming actually an oak tree. IV. The previous material is largely directed to the ends of biological explanation. But it helps to flesh out Aristotle's physics, also. 1. On his account, motion is explained by the fact that natural substances have natural places. For instance, physical bodies belong at the geometric center of the universe. This explains why they fall to the earth. Water naturally floats on water. Air naturally rises above water. Fire naturally belongs above air, as evidenced by an open flame's seeming tendency to lick up at the sky when burning. 3 2. They are not ordered this simply, in fact, only because of the disruption imparted to the elements by the motion generated by the movements of the universe around the earth. V. Aristotle's physics also supplements his account of astronomy. But for this he needs to add a fifth element, quintessence, from which the heavens are made. 1. Remember Eudoxus (previous lecture). He devised an ingenious planetary system based on spheres designed to account for the fact that the moon, sun and planets don't move as regularly as they would if they simply traveled in perfect concentric spheres around the earth. A. The overall geometry of the universe: (a) Earth is in the geomantic center. (b) Around earth are 27 concentric spheres, all rotating around the earth. (c) The last sphere caries the fixed stars; the others are the sun, the moon, and the five planets. (d) Each planet needs four spheres apiece. The sun and moon need three spheres apiece 4 B. Consider the moon. (Bear in mind, I'm not asking you to remember all the details of this. Just get the idea of the general mechanism and a sense of just how complicated it is.) (a) The outer sphere rotates each day with the stars tacked onto the inside of it, and with axis perpendicular to the zodiac. (b) The next middle sphere rotates on a circle at an angle to the zodiac circle from east to west. (c) The inner sphere rotates about an axis inclined to the axis of the second at an angle equal to the highest latitude attained by the moon, and from west to east. The moon is fixed on the great circle at this angle. (d) It looks like this: 5 C. Aristotle took this, tweaked it till he needed more than 50 spheres. Most of these are intended to help the projected movements come out right. But included in this number are also a set of crystalline spheres between those carrying the planets, to keep them from disturbing each other. D. Drastically simplified, it looked like this: E. As mentioned above, all substances here are where they are supposed to be. Each substance has a natural place. Earth belongs at the center, water belongs on top of earth, etc. But the elements get mixed up by the movement of the spheres, generated by the prime mover at the periphery. 6 F. At the center, the stuff is heaviest and has the least actuality and the greatest potentiality (i.e., greatest susceptibility to change.) At the periphery are the stars and the prime mover, which are very light and have the greatest actuality and least potentiality (i.e., they act on other things and are least susceptible to change). HON 280 -- LECTURE SIX (HELLENISM) THE DEVELOPMENT OF SCIENCE I. Last time, we finished with Aristotle. Note that certain aspects of his cosmology exist in religious thought even now (think about how children think about heaven and hell. It was formally dominant even more powerfully (think about Dante's trilogy). II. Hellenism was the period of time running from the death of Alexander the Awesome (323 BCE) to the fall of Greek political power to the Romans. The latter date is differently reckoned by different historians. Some reckon it to be the year when the Romans conquered the Greek heartland 146 BCE). Others reckon it to be the year that Rome conquered Egypt (30BC), since Egypt was the last remaining influential bastion of Greek civilization (having been conquered by Alexander). III. During this period, Aristotelian physics faced competition from the atomists. Remember them? Their central doctrines were: (1) all that exist are differently assembled collections of atoms in the void, (2) the ways in which these atoms assemble and disassemble are governed by chance collisions, not 7 purpose). That is, things happen in nature due to causes, NOT for reasons. IV. The major advocate of atomism during this time was Epicurus (270 BCE). Interestingly, he offered atomism as the basis of a moral doctrine, or at least as a doctrine telling us how best to live. Specifically, he thought that atomism alleviated two central obstacles to the good life: (1) Fear of the gods. (2) Fear of death. (Refer here to your own lecture notes for details.) 8