A case_study_in_qualitative_research

advertisement

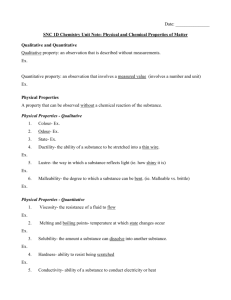

http://informationr.net/tdw/publ/papers/1981SSIS.html A CASE STUDY IN QUALITATIVE RESEARCH? T. D. WILSON University of Sheffield, England Abstract This paper reflects upon the methodology adopted in Project INISS. The author begins by noting that a problem may be approached simultaneously from more than one paradigmatic stance, and that a given method may be used by researchers working within different traditions. His intention in his research was to work within the conventional paradigm, and his choice of method (structured observation) in no way reflected a predilection for qualitative research. It was nonetheless the case that, when faced with a mass of quantitative data, there were a number of advantages in combining quantitative and qualitative modes of analysis and reporting. The author goes on to consider various research management issues in field research of this kind. He concludes by seeing his aim as that of finding a means of gathering more meaningful quantitative data, rather than rejecting quantitative methods as such. His feeling is that 'if anything is to be learned from the work, it is that a more sensitive approach to the collection of data and accounts will pay dividends in insights, theory, and practical ideas for improvements in information services. INTRODUCTION The overall research strategy of Project INISS was that of 'action research'. In other words, the aim was to involve staff of social services departments in innovations in information provision and information transfer, to discover what succeeded or failed and why. The data-collection phase of the Project, therefore, was seen as a preliminary to practical involvement in social services departments. Its aim was not only to collect data but also to give the research team direct experience of the field of investigation, to establish the credibility of the team in departments with which a lengthy association was foreseen, and to provide insights into the day-to-day work of departments and the information and communication consequences of that work. Various aspects of the data-collection phase have been reported upon elsewhere, particularly in Wilson and Streatfield (1977), Wilson et al. (1979) and Streatfield and Wilson (1980). Structured observation as a method of investigation has been assessed in an earlier issue of SSIS (Wilson and Streatfield, 1981). This short note will not attempt to duplicate these reports but will be restricted to some methodological and research management aspects of the observation phase of the study. THE CHOICE OF METHOD The choice of research method is clearly related to the overall 'paradigm' within which one chooses to work. Guba (1980) has characterized the paradigms 'favoured by different groups at different times' and his statement is set out in alternative form in Table 1. It is important to note that a problem may be approached from more than one paradigmatic stance more or less simultaneously and that a given method may be used by researchers working within different traditions. This last fact is certainly true both of interviewing and observation. Table 1. Ways of knowing (after Guba, 1980) Paradigm Fundamental technique View of truth Example Logical Analysis Demonstrable Mathematics Judgmental Sensing Recognizable Wine tasting Adversarial Cross-examination Emergent Jury trial Modus operandi Sequential testing Trackable Forensic pathology Demographic Indicators Macroscopically determinable Economics Religious Revelation Absolute and given Catholicism Scientific Experimentation Confirmable Physics Naturalistic Field study Ineluctable Ethnography The choice of structured observation as a research method for Project INISS was not the result of a predilection for the 'naturalistic paradigm', rather it was first, the result of an accident; secondly, it was related to an intention to work within the 'scientific paradigm' and only thirdly did an awareness of its relation to the naturalistic paradigm and qualitative research emerge. The accident was one of those instances of serendipity that happen to any researcher: the discovery on a colleague's desk of Mintzberg's 'The nature of managerial work' ( 1973) about to be returned to the British Library Lending Division. The intention became, thereafter, to use Mintzberg's method to collect quantitative data on communication and information-seeking events. As reported elsewhere (Wilson and Streatfield, 1977) the method served that purpose: 5,839 communication events analysed by 16 variables provided almost an embarrassment of data. However, before the first week of observation it became obvious (partly through further attention to Mintzberg, partly through the training exercises and partly as a result of reading John M. Johnson's 'Doing field research' (1975) - another serendipitous event) that a narrative mode of reporting, in addition to the statistical mode, would: make the quantitative data more intelligible; provide a more effective way of reporting back to the people observed; reveal the social reality of the research settings more fully; and provide the research team with an effective means of sharing and pooling their perceptions of the departments in which they worked. Thus, structured observation as used in Project INISS was an example not of a wholly qualitative research approach but rather of a combination of a method which has both quantitative and qualitative applications with qualitative analysis and reporting. In a recent paper Gene E. Hall set the scene for an analysis of the management of qualitative research by noting that: 'There is reason to believe that many of the new qualitative research attempts will reflect overly simplistic approaches to answering research questions and naiveté about the complexities of doing this type of research.' (Hall, 1980: 350), and by identifying the following tasks the research manager needs to perform in order to avoid the hazards of the 'bandwagon' effect: a. conceptualizing the research project and determining if ethnographic methods are called for; b. recruiting and training ethnographers; c. negotiating ethnographers being on-site; d. developing formats for data recording; e. developing procedures for data transmittal to the research center; f.maintaining communication and coordination between the ethnographer, site personnel and researcher; g. determining strategies to reduce the volumes of data so that the. meaning and richness are not lost; and h. interpreting and relating the qualitative data in meaningful ways. (Hall, 1980:351) Hall was writing about educational research/but the same dangers and difficulties exist in information research and his analysis of tasks will be used here as a basis for discussion. However, two of the topics (b and d above) have been dealt with in some detail elsewhere (Wilson and Streatfield, 1981) and will not be further elaborated here. WHY WAS A QUALITATIVE APPROACH NECESSARY? It has been noted above that structured observation was adopted as a quantitative technique and, therefore, the question becomes, 'Why was field research, rather than survey research, thought desirable?' As research director, the author had four reasons for this choice of strategy. The first was a dissatisfaction with the results of large-scale survey research in the information field. Though useful in terms of providing generalized descriptions of certain aspects of information-seeking behaviour, survey research appeared to provide little in the way of insight into motivations for information-seeking and little in the way of discrimination between different categories of information users that could guide information service practice. The second reason was related to the first: survey methods appeared to have been based chiefly on questionnaires and interview schedules constructed within the information worker's frame of reference rather than that of the group being investigated. This was clearly evident in the couching of questions about information use in terms of physical forms of presentation (books, journals, graphic materials, etc.) rather than in terms of categories that might be more familiar and more meaningful to the information user. Thirdly, the author (and at least two of the researchers) were almost totally ignorant of what the standard texts on social work actually meant in terms of problems, activity, and behaviour in social services departments. It was believed that, without an understanding of the day-to-day business of departments it would be impossible to conceive of information needs in the same way as those working in the field. Observation, therefore, offered a means for being educated about a field of information use. Finally, the author's emerging theoretical position on the nature of information needs: see Wilson (1981) related information-seeking behaviour to work-role and taskperformance. If the theory were to be further developed, field research was essential. From this analysis it will be clear that field research is not necessary in every investigation. Where background information and experience is otherwise available, where false categorizations can be avoided and where clear theoretical formulations already exist, field research may be an unnecessary luxury. NEGOTIATING ACCESS Although increasing in popularity, ethnographic field research in organizations is still a sufficiently unusual strategy for one to expect problems in negotiating access. In fact, as far as Project INISS was concerned, the actual method of data collection seemed not to be the most critical element in negotiation. Once the department had accepted that the area of research was one which could provide useful information, the method by which data were collected was secondary. Two factors may have promoted this fairly ready acceptance of the method: first, that part of a social worker's training involves observing and being observed, and second that the research team was to be in departments for only one week. Had the research involved lengthier periods of field work more difficulty might have been experienced. Naturally, negotiation involved satisfying the participants on a number of issues. However, these would have arisen in any kind of investigation. They involved questions on the confidentiality of the data, clearance for publication, and the extent to which the department was likely to benefit. The process of negotiation continued into the actual observation weeks as far as the individuals observed were concerned: they too raised questions of confidentiality, of the motives for the research (was some kind of '0 and M report' on their activities envisaged, for example), and of the intended outcomes of the research in terms of further action, books, etc. Their concern was clearly, in part at least, that they should not be treated merely as 'subjects' for some totally 'academic' piece of research. In negotiating subsequent phases of the research it was evident that the experience of observation was as satisfying to those in the departments as it was to the researchers and the fact that promises to report back to individuals and the department had been kept by the research team was also important. Feedback of this kind is practised insufficiently by researchers and the anonymous 'subjects' who provide data through questionnaire completion are more readily forgettable than Syd, or Margaret, or Trevor with whom one has spent a working week. DATA TRANSMISSION AND MAINTAINING COORDINATION Because the periods offieldwork were each limited to one week, transmitting data back to the research unit presented no problem: the researchers brought the records back to the office at the beginning of the week following each observation period. Nor was coordination a particular problem. The author participated in two of the weeks of observation and, in addition, visited the team during the first week. Again, the short duration of the observation period was advantageous since the researchers were able to discuss the experience in depth in the intervening weeks. During observation, communication among members of the team was easy as all stayed in the same hotel and frequently met during working hours as the people they were observing came into contact at informal and formal meetings. REDUCING THE VOLUME OF DATA AND INTERPRETING DATA One of the principle problems of ethnographic fieldwork is that it produces a large amount of data. However, it should be remembered that the field phase of Project INISS was intended to produce quantitative data and the data- recording format had been designed with this in mind. Thus, records were collected of 5,839 communication 'events' and reduction became a matter of encoding and statistical analysis in the classic 'positivist' manner. However, these records also served as the basis for narrative accounts of the week of observation to be given to each person observed. There were twenty-two accounts in all, amounting to more than 300 pages of qualitative data. Clearly, these reports were reductions of much more information both in the data and in the researchers' heads and were focused upon what might be called 'information behaviour' rather than upon total behaviour. In the final report of the first two stages of Project INISS (Wilson and Streatfield, 1980) these accounts have been reduced still further into a narrative account of 'A week in the life of . . .' a social services department. The aim was to give the reader the 'flavour' of a department at work to set against the rather more arid statistical reporting. Throughout this process classification and categorization were used to assist the reduction of complexity and to aid interpretation. Thus, the individuals observed were categorized by work-role, their activities were classified by an amended version of Mintzberg's 'managerial roles', and the subject of communication was classified by a simple, two-facet classification scheme derived from the data. Events were categorized in all of these ways and this aided not only interpretation but also the narrative report-writing. CONCLUSION A question mark appears in the title of this piece because it is questionable how far the observation phase of Project INISS can be considered to be an example of qualitative research in the information field. Rather than rejecting quantitative methods the author sought a means of gathering more meaningful quantitative data, less influenced by pre-determined, 'library-like' frameworks. In the event, the experiences were reported in both quantitative and qualitative terms and, if anything is to be learned from the work, it is that a more sensitive approach to the collection of data and accounts will pay dividends in insights, theory, and practical ideas for improvements in information services. All of this has benefits in an area not mentioned by Hall, that is, the dissemination of results. Not only can research reports be more vivid in their re-creation of the research settings, but the accumulated experience is invaluable in reporting to and encouraging organizations to adopt changes in information provision. In the case of Project INISS this has been attempted not only through individual reporting to the 'subject' departments, but also by mounting one-day training courses under the auspices of the National Institute of Social Work. In the author's opinion, it would have been impossible to conduct those courses successfully without the field experience that structured observation allowed. REFERENCES GUBA, E. G. (1980). Naturalistic and conventional inquiry. Paper delivered at the AERA Symposium 'Considerations for educational inquiry in the 1980s'. Boston, Mass. HALL, G. E. (1980). Ethnographers and ethnographic data: an iceberg of the first order for the research manager. Education and Urban Society, 12, 349-366. JOHNSON, J. M. (1975). Doing field research. New York: Free Press. MINTZBERG, H. (1973). The nature of managerial work. New York: Harper and Row. STREATFIELD, D. R. and WILSON, T. D. (1980). The vital link: information in social services departments. Sheffield: Community Care and the Joint Unit for Research in Social Services. WILSON, T. D. (1980). Recent trends in user studies: action research and qualitative methods. Berlin: Freie Universitat Berlin, Institut fur Publizistik und Dokumentations-wissenschaft. (Projekt Methodeninstrumentarium zur Benutzerforschung in Information und Dokumentation-Projektinformation MIB PI 11/80). Retrieved 11 October, 2003 from http://informationr.net/ir/5-3/paper76.html WILSON, T. D. (1981). On user studies and information needs. Journal of Documentation, 37(1), 3-15. WILSON, T. D. and STREATFIELD, D. R. (1977). Information needs in local authority social services departments: an interim report on Project INISS. Journal of Documentation, 33, 277-293. WILSON, T. D. and STREATFIELD, D. R. (1980). You can observe a lot. . . : a study of information use in local authority social services departments. Sheffield: Postgraduate School of Librarian-ship and Information Science. (Occasional paper no. 12). Retrieved 11 October, 2003 from http://informationr.net/tdw/publ/INISS/ WILSON, T. D. and STREATFIELD, D. R. (1981). Structured observation in the investigation of information need. Social Science Information Studies, 1, 173-184. WILSON, T.D., STREATFIELD, D.R. and MULLINGS, C. (1979). Information needs in local authority social services departments: a second report on Project INISS. Journal of Documentation, 35, 120-136. Originally published in Social Science Information Studies, 1, 241-146