URINARY INCONTINENCE

advertisement

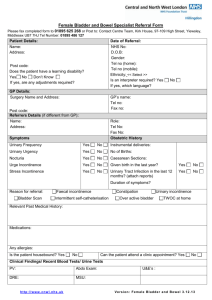

Urinary Incontinence August 2004 Author: E. Gordon Margolin, M.D. Competencies: Medical Knowledge, Patient Care Learning Objectives: After reading this information you should be able to: 1. 2. 3. 4. Identify six causes of transient urinary incontinence. List and describe four types of established urinary incontinence. Define the neurologic mechanisms involved in micturition. Identify applicable treatment methods for each type of established incontinence. 5. Discuss the physiologic changes in the lower urinary system of the elderly, which contribute to “age-associated” incontinence (other than changes that are gender-specific). 6. Recognize the emotional impact incontinence can have on a patient Key Points Urinary incontinence is a frequent and often neglected problem in the elderly. A full understanding of the consequences of failure to address the problems of incontinence is important in primary care. Separating Transient from Persistent incontinence is the first step in guiding management. Knowledge of the various types of incontinence and the approach to the care and treatment of each type is critical to prevent inappropriate, potentially deleterious, management. Introduction Urinary incontinence, especially in the elderly population, is a common problem causing very significant social and psychological issues for the patients—often ignored by the practicing physician. Content Urinary Incontinence, especially in the elderly, is a complex geriatric syndrome often overlooked or ignored by primary physicians, and known to create substantial psychological and social problems for those affected. The International Incontinence Society defines this issue as the uncontrolled loss of urine, generally in an undesirable place, creating social and hygienic problems. The exact prevalence is difficult to determine, but is said to involve as many as 30% of community dwelling elderly, 50% of those hospitalized and 70% of nursing home residents. The estimated annual cost of almost 30 billion dollars in the U.S. alone reflects labor, laundry, institutional costs, products, and complicating events. It is difficult to measure the impact on quality of life, isolation, depression, caregiver strain or frequency of institutionalization. Indeed, the failure of patients to report the problem and the lack of interest and attention by physicians are significant barriers to care and amelioration of the issues. Urinary incontinence is an age-associated problem, though it can be present in individuals of any age. Causes are complex, many of which are related to changes in the physiology and anatomy of the lower urinary tract. The bladder tends to get smaller with age; the number of uncontrolled detrusor contractions increase, there is an increase in post void residual volume and a decrease in bladder contractility, and lesser responses to sensory impulses. In addition, the ability to postpone voiding may be impaired related to changes in mentation and mobility and manual dexterity. Diurnal rhythmicity of urine production may result in larger volumes of urine overnight. Of course, the expected alterations of the prostate in men and of the vagina and supporting tissues in women also impact upon normal micturition. Acute, or transient, causes of incontinence are often confronted in acutely hospitalized patients. The mnemonic of DIAPPERS serves as a guide: Delirium, Infection, Atrophic urethritis and vaginitis, Pharmaceuticals, Psychological, Excessive urine production, Restricted mobility and Stool impaction. Established incontinence (duration of at least two months) is described by four TYPES (not diagnoses) of incontinence, namely, Stress, Urge (subtype—overactive bladder), Overflow and Functional. Mostly, several of these phenomena occur simultaneously, referred to as Mixed Incontinence. Some classifications add a fifth type, namely Drug Induced. Each cause or type of incontinence must be separately identified for appropriate treatment and interventions, as incorrect application of therapy can worsen or aggravate the problem. STRESS incontinence is due to incompetence of the sphincteric mechanism, allowing spurts of urine to escape when there is an increase in intraabdominal pressure, due to coughing, lifting, etc. The sphincter is innervated by sympathetic nerves, so that alphaagonists may be used to tighten the sphincter (which is opposite from alpha-blockers used in treatment of BPH to lessen sphincteric tone). Sometimes, local applications of estrogen creams will help in the postmenopausal woman. Surgical correction may be necessary in selected instances. Behavioral techniques are described below. URGE incontinence results from an overactive detrusor when intraluminal pressure exceeds the ability of the sphincter to prevent leakage, resulting in losses of small to large volumes of urine and causing a significant nuisance effect. Causes can vary from infections to stones to neurogenic, but mostly the causes are indeterminate and may truly reflect on changes due to aging. Generally, patients sense the need to void, but they cannot always get to the bathroom or position themselves quickly enough to prevent accidents. Products are often worn by these patients for protection. Since the detrusor is mainly innervated by cholinergic fibers, the use of anticholinergics is the drug treatment of choice. The currently used drugs, namely Ditropan (oxybutynin), Detrol (tolterodine) and Oxytrol (patch-applied oxybutynin), are limited in efficacy and safety. They are systemically acting drugs, which can cause dry mouth, mydriasis, confusion, constipation and cardiac arrhythmias and so must be used cautiously. Drugs better localized to the bladder problem are in the pipe-line. Overactive bladder syndrome known as OAB (“gotta go, gotta go”) does not always result in urinary losses, just severe urgency and frequency. Treatment is the same as for urge incontinence. For both STRESS and URGE, singly or in combination, the current recommended first line of treatment is behavioral. The use of Kegel exercises (see attachment – this will be available as a patient care handout) to heighten ability to contract the external sphincter voluntarily (somatic nerve supplied) will help prevent stress losses. Bladder training techniques, namely gradually increasing the amount of urine the bladder will contain, will help reduce urge incontinence. Prompted voiding by caregivers of mentally compromised individuals is another behavioral technique. OVERFLOW incontinence occurs, with symptoms similar to those of URGE, when the overdistended bladder—from two opposing possibilities: detrusor paralysis or outflow obstruction—suddenly overflows. High postvoid residual volumes will generally differentiate this type of incontinence from URGE. Management may require surgical intervention for mechanical obstruction or recurrent catheterization for the paralyzed bladder. Danger: assuming urge incontinence in an overflowing bladder and treating with anticholinergics could cause serious harm. FUNCTIONAL incontinence does not involve the lower urinary tract, but refers to limitations of the patient’s ability to self-toilet, due to physical problems such as strokes or arthritis, to mental problems such as dementia or to environmental circumstances such as restraints or locked or remote bathrooms. Simple assistance, placement of commodes and urinals, and environmental modifications may solve the problems of patients with these kinds of problems. Physicians in the office or clinic must inquire about the presence or absence of incontinence. The office workup includes a history of the patient’s symptoms, including amount of losses, timing of accidents, associated bladder or pelvic problems, and a full list of medications. The focused physical exam includes a mental status and general physical capabilities, abdominal exam, pelvic and rectal exams, and neurologic assessment. Tests that can easily be accomplished include urinalysis, appropriate blood tests, voiding diary, and postvoid residual (catheter or ultrasound). Behavioral therapy for stress, urge or functional incontinence should precede use of any medications. Failure to solve the problem may ultimately require referral to urologist, gynecologist or other appropriate specialist. Urinary incontinence is not a diagnosis but a symptom of an underlying problem, which must be assessed and aided. Urinary incontinence is not an inevitable part of the aging process, though it is often age-associated. CASES A 78-year-old woman comes to your office because of urinary incontinence that includes urinary urgency, two to three episodes of nocturia each night, and leakage on the way to the toilet almost every time she voids. Her symptoms have progressed gradually over several months. She also has involuntary urine loss with coughing and sneezing and when she has an upper respiratory infection. She wears pads at all times. There are no other significant urinary symptoms or past genitourinary history. History includes congestive heart failure, GE reflux, glaucoma, and osteoporosis. She takes enalapril, furosemide, potassium, timolol eye drops, calcium and ranitidine. 1. Which of the following types of incontinence do you suspect from this story? a. Stress b. Urge c. Overflow d. Functional e. Drug-induced 2. The history fails to inquire about patient’s feelings about this problem? Which of the following is most likely? a. There is no reason to investigate social or psychological concerns b. It is unlikely that incontinence interferes with quality of life c. Patient could be depressed and isolated. d. Getting involved with ancillary concerns should await a full diagnosis Physical examination shows an ambulatory, cognitively intact woman with clear lungs, regular heart rhythm without S3, 2+ pitting pedal edema, and no focal neurologic signs. Pelvic examination shows pale, smooth vaginal mucosa without signs of inflammation, a cystocele that descends about 2 cm below the urethra with coughing (which causes urine to drip from urethral meatus), and no masses or tenderness on bimanual exam. Rectal examination is normal. 3. Which of the types of incontinence can now be eliminated from your differential diagnosis? a. Stress b. Urge c. Overflow d. Functional e. Drug-induced The patient voids 325 ml of urine on request and is catheterized for a postvoid volume of 60 ml. Urinalysis is normal. 4. Which type of incontinence can now be deleted from consideration? a. Stress b. Urge c. Overflow d. Functional e. Drug-induced 5. How much residual urine is the cutoff between normal and abnormal? a. 0 ml b. 50 ml c. 100 ml d. 200 ml 6. What would be the rationale for the selection of each of the following items in management of this problem? a. Prescribe oxybutynin, 2.5 mgm twice daily and at bedtime b. Prescribe estrogen vaginal cream, 1 g at bedtime, and pseudoephedrine by mouth twice daily c. Teach the patient pelvic muscle exercises and bladder training techniques d. Do urodynamics to determine if detrusor instability and reduced bladder capacity are present e. Refer her to a gynecologist for consideration to surgery to correct the cystocele. 7. Which of the options in question 6 would be the preferred next step in management? a. Option a b. Option b c. Option c d. Option d e. Option e ANSWERS Question 1: a, b, c and e are possible. Answer e would be unlikely, however, if furosemide had been used longer than the duration of her complaints of incontinence. Timolol may also affect bladder function, but probably not an issue if eyedrops are use appropriately. Question 2: c is very important, as concerns for the “whole patient” and other issues of frailty can be coupled with complaints of incontinence. Question 3: d, functional, can be excluded, as patient is “ambulatory and cognitively intact”. Question 4: c, overflow is generally associated with large residual volume. Without this measurement, it may be not possible to differentiate symptoms of urge from symptoms of overflow. Since the management is so different, the use of postvoid residual is the one test that is highly recommended in the workup. Question 5: d is certainly correct as defined by urologists. However, there is a “no man’s land” between 100 and 200 ml as some believe that >100 ml is too high a residual (when properly performed). (Therefore, c could also be considered correct.) Question 6: a. Treatment with anticholinergic drugs is appropriate to relax the overactive bladder, which is creating the problem of urge. The bladder is innervated mainly with cholinergic fibers, responsible for contraction of the detrusor. Side effects from anticholinergics, however, are a major concern; therefore, the low doses of the drug to start. b. Stress incontinence reflects a problem with the sphincteric mechanism. Since the internal sphincter is innervated by sympathetic fibers, alpha agonists such as pseudoephedrine can tighten the sphincter. In postmenopausal women the absence of estrogen may adversely affect not only the vaginal mucosa but also the trigone and urethra, so estrogen replacement locally may be useful. c. Behavioral therapy has been declared to be very useful in the management of Stress and Urge incontinence, mainly because there are no needs for invasive interventions and no medications with concerns of side effects. d. Urodynamic studies will provide a great deal of information about the physiology and anatomy of the lower urinary system. These tests may be a necessary part of the workup, dependent on history and response to therapeutic trials. e. Surgical intervention to correct cystoceles and procidentia can be an important part of the needs of some women with incontinence. Many times the gynecologist may give a trial with pessaries first. Question 7: c is the correct answer. The current “party line” is always to try behavioral therapy before other management techniques. This is based on a study by Fantl who felt that stress and urge could be reduced an average of 70% with appropriate behavioral interventions. REFERENCES 1. Weiss BD. Diagnostic evaluation of urinary incontinence in geriatric patients. Am. Fam. Physician 1998;57:2675-2684. 2. Ouslander JG. Management of overactive bladder. NEJM 2004;350:786-799. How To Do Pelvic Floor Muscle Exercises (Kegel's) Many Women with urinary incontinence can decrease their urinary leakage during coughing, laughing, sneezing, or other activities by exercising the muscles of the pelvic floor. These exercises are often called "Kegel exercises" after the doctor, Arnold Kegel, M.D., who first described them. To find the muscle you need to exercise, imagine that you have a tampon in your vagina that is falling out and you must tighten your muscle in order to hold it in. The muscle you tighten is the muscle you should exercise. Another way to find the right muscle, the bulbocavernosis muscle, is to sit on the toilet, place one finger in the vagina and contract that muscle around you finger. The muscle you use to tighten around your finger is the muscle you should exercise. Your doctor can help you determine which muscle to contract and make sure you are doing it properly by checking you during a pelvic examination. Do not make a habit of doing these exercises by starting and stopping your urine flow while voiding! You can teach yourself bad bladder habits and develop voiding difficulty by doing this! Instead, you should practice your exercises at other times. Stopping your urine stream during voiding is taught by others only to help you find the correct muscle to contract. Pelvic muscle exercises can be done in many different ways. We will give you instructions on how to do the type of exercise described by Dr. Kegel. Since continued vigorous exercise can lead to muscle soreness and fatigue, don't try to start out at maximum exercises all at once. Spread them out over the course of the day. We suggest starting with 25 muscle contractions divided into 3 daily sessions. This should take 5 minutes 3 times a day. You should eventually build up to 20 minutes (100 contractions) 3 times a day. If you do have muscle soreness starting out, try doing the exercises vigorously every other day instead. this will allow your muscle to recover from the fatigue of exercise. These exercises can be done anywhere and at any time. You may find it helpful to associate an activity with your muscles, such as doing them while stopped at a red light, during a TV commercial, talking on the phone, or doing various household chores such as ironing, washing dishes, cooking, etc. The important think is to get in the habit of doing them! KEGEL’s Exercises Initially - Tighten the pelvic floor muscles for count of six and relax for six seconds. Each contraction cycle should last 12 seconds or 5 contractions a minute. Repeat 25 times. Do this 3 times each day - total 75 contractions Week 2 - Tighten the pelvic floor muscles for 6 seconds every 12 seconds (5 per minute) for 10 minutes, 50 contractions. Do this 3 times each day - total 150 contractions Week 3 - Tighten the pelvic floor muscles for 6 seconds every 12 seconds (5 per minute) for 15 minutes, 75 contractions. Do this 3 times each day - total 225 contractions. Weeks 4-24 - Tighten the pelvic floor muscles for 6 seconds every 12 seconds (5 per minute) for 20 minutes, 100 contractions. Do this 3 times each day - total 100 contractions After 24 months - Continue maintainence at 10 minutes three times a day or 15 minutes twice a day, total of 150 contractions a day You may notice some soreness in the pelvic muscles and around the vaginal opening once you start exercising regularly. Do not worry about this - it is only soreness associated with increased muscle activity. The benefits of these exercises will continue ONLY as long as you do them! Use it or lose it! You should expect to have to do these exercises regularly for three months before you notice an improvement in your urine loss. At six months of regular exercise you will get maximum effect. Source: http://www.wdxcyber.com/kegel.htm, accessed 8.18.04