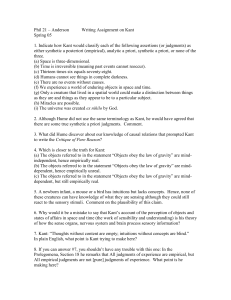

Kant and double affection: solving the problem

advertisement