Medical nutrition therapy for fat malabsorption in liver

advertisement

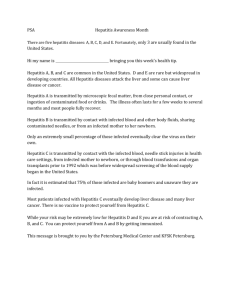

Liver Disease: The Role of Nutrition The major forms of liver disease are: Acute viral hepatitis Fulminant hepatitis Chronic hepatitis Alcoholic hepatitis Cirrhosis Acute viral hepatitis The five forms of acute viral hepatitis are hepatitis A, B, C, D, and E. Hepatitis A: Hepatitis A is found in water, food, and sewage, It is spread via the oral-fecal route. It rarely leads to chronic complications. However, 15% of patients will have relapsing symptoms within 6–9 months. Complete recovery occurs in 95% of cases. Thirty-three percent of the population has evidence of past infection. Vaccination is available. Hepatitis B: Hepatitis B is contracted through blood, semen, or saliva. It can lead to a chronic condition sometimes resulting in cirrhosis and liver failure, with 5%–10% of adults with hepatitis B developing chronic hepatitis and 10% or more of these cases developing into cirrhosis. A 15%–25% fatality rate exists from hepatitis B. Vaccination is available. Hepatitis C: Hepatitis C is contracted through blood, semen, or saliva. It can lead to a chronic condition, sometimes resulting in cirrhosis and liver failure, with 75%–90% of people with hepatitis C developing chronic hepatitis and 20%–30% of these cases developing into cirrhosis. A 1%–5% fatality rate exists from hepatitis C. Vaccination is not available for hepatitis C. Hepatitis D: Hepatitis D only develops in some people who have hepatitis B. Progression to cirrhosis is common in people with hepatitis B and D, and 2%–20% of people will develop acute liver failure. Vaccine for hepatitis B is available. Hepatitis E: Hepatitis E is rare in the United States (most likely to occur in South Asia and North Africa) and is contracted through the oral-fecal route. Hepatitis E is acute, not chronic. No vaccination is available. Hepatitis also is caused by the Epstein-Barr virus, cytomegalovirus, herpes simplex, yellow fever, and rubella. Hepatitis progresses in four phases: First phase (early prodromal phase): Symptoms include fever, arthralgia, arthritis, rash, and/or angioedema. Second phase (preicteric phase): Symptoms include malaise, fatigue, myalgia, anorexia, and nausea and vomiting. Third phase (icteric phase): Jaundice occurs. Forth phase (convalescent): Symptoms may subside. Fulminant hepatitis Acute liver failure with hepatic encephalopathy 75% of cases result from acute hepatitis, with 1% of hepatitis A and B patients developing fulminant hepatitis The remaining 25% of cases result from chemical toxicity, Wilson’s disease, fatty liver of pregnancy, Reye’s syndrome, hepatic ischemia, hepatic vein obstruction, or disseminated malignancies Risks of fulminant hepatitis include: – Cerebral edema – Bleeding – Cardiovascular problems – Renal problems – Pulmonary complications – Changes to acid-base balance – Electrolyte imbalances – Sepsis – Pancreatitis 50% fatal unless timely liver transplantation occurs Chronic hepatitis Diagnosed after 6 months of acute hepatitis, with evidence of liver disease and confirmation of unresolved hepatic inflammation through biopsy Autoimmune, viral, metabolic, and toxicological issues can cause chronic hepatitis (most common causes are hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and autoimmune hepatitis) Alcoholic liver disease, alcoholic hepatitis, and cirrhosis Caused by damage to the mitochondrial membrane Risk factors for developing alcohol-related liver problems include: – Female gender – Genetic predisposition – Exposure to other drugs combined with heavy alcohol consumption – Infection with certain viruses – Immune issues – Poor nutrition status Three stages of alcoholic liver disease: – Hepatic steatosis—fatty liver disease, reversible if drinking stops – Alcoholic hepatitis—reversible if drinking stops – Cirrhosis—not reversible Primary biliary cirrhosis An immune-mediated disease caused by the progressive destruction of intrahepatic bile ducts 95% of total incidence occurs in females A chronic disease that progresses slowly and results in cirrhosis and portal hypertension People with primary biliary cirrhosis must undergo liver transplantation or the disease becomes fatal Many nutritional problems develop, including osteopenia, hypercholestrolemia, and deficiency of fat-soluble vitamins Sclerosing cholangitis A chronic cholestatic condition Possibly an immune-mediated disease Results in portal hypertension, hepatic failure, or cholangiocarcinoma 70%–90% of people with sclerosing cholangitis also have irritable bowel disease, particularly ulcerative colitis More common in men than in women Nutritional problems that are likely to develop include steatorrhea with subsequent fat-soluble vitamin deficiency, hyperparathyroidism, osteomalacia, and rickets Treated with immunosuppressants, but liver transplant is often necessary Hepatic encephalopathy Characterized by impaired mental status, neuromuscular disturbances, and altered consciousness Ammonia accumulation is thought to be a causal factor Amino acid imbalance exists in which branched chain amino acids (BCAAs) valine, leucine, and isoleucine are decreased, changing the plasma ratio of BCAA to aromatic amino acid (AAA). Medical nutrition therapy for cirrhosis Serve smaller meals because of early satiety and anorexia: – Smaller meals also may help to promote a positive nitrogen balance and prevention of hypoglycemia Offer oral nutritional supplements to meet nutrient needs, if needed Consider nutritional support, if patient is unable to consume 0.8 grams (g) protein /kilogram (kg)/day and 30 kilocalories (kcal)/kg/day May necessitate 120%–140% of resting energy expenditure (REE) in end-stage liver disease without ascites; and up to 150%-175% of REE if ascites, malabsorption, or infection is present Make sure to obtain dry weights for reassessment purposes Understand that liver failure reduces glucose production and decreases peripheral utilization; coupled with a change in hormones, such as insulin, glucagon, cortisol, and epinephrine, the body develops preference for lipids and amino acids Have 25%–40% of total calories from lipid Provide 1.2–1.3 g protein/kg/day to promote positive nitrogen balance, or 1.5 g protein/kg/day if patient shows signs of severe ascites or gastrointestinal bleeding Recommend: – Vitamin and mineral supplementation for end-stage liver disease, including all of the B and fat-soluble vitamins – Thiamine, vitamin B6, vitamin B12, folate, and niacin for Wernicke’s encephalopathy – Iron supplementation for gastrointestinal bleeding Know that zinc, magnesium, and copper are malabsorbed in chronic liver disease with steatorrhea Realize that 10%–37% of patients with cirrhosis will develop overt diabetes mellitus Medical nutrition therapy for portal hypertension Know that in the acute stage, initiation of total parenteral nutrition (TPN) probably is necessary Realize that repeated endoscopic therapy is likely to cause esophageal stricture or dysphagia Understand that shunt placement increases the risk of encephalopathy and reduces nutrient metabolism Medical nutrition therapy for ascites Recommend fluid restriction Watch for loop diuretic side effects, including hyponatremia, hypokalemia, hypomagnesemia, hypocalcemia, and hypochloremic acidosis Monitor weight, abdominal girth, urinary sodium concentration, blood urea nitrogen (BUN), creatinine, albumin, uric acid, and electrolyte levels, if patient is prescribed diuretics Recommend 2 g/day for sodium restriction Ensure that patient receives adequate protein Medical nutrition therapy for hepatic encephalopathy (including fulminant hepatitis) Understand that ammonia is an important causative factor, because the liver can not detoxify ammonia to urea Realize that even though some people believe that dietary protein causes an increase in ammonia production, this is unproven: – Protein restriction is not recommended, with some studies showing that this practice is possibly quite harmful Recommend a BCAA formula for patients who cannot tolerate standard protein sources and are nonresponsive to medication Know that vegetable protein and casein are the preferred sources of protein for patients with hepatic encephalopathy (according to some studies), because they contain less AAA and more BCAA than other sources of protein Monitor glucose regularly Medical nutrition therapy for fat malabsorption in liver disease Replace long-chain triglycerides with medium-chain triglycerides, because they are more readily digestible Recommend a 40-g fat diet: – If diarrhea does not resolve quickly as a result of this diet, discontinue the diet because of the risk of furthering malnutrition Medical nutrition therapy for liver transplant Know that malnutrition is common pretransplant Recommend small, frequent, nutritionally complete meals, with enteral feedings as necessary Realize that food-drug interactions are common Provide nutritional intervention post-transplant, as necessary, for comorbid conditions, such as obesity, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, and diabetes References and recommended readings Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Hepatitis A information for health professionals. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/HAV/index.htm. Accessed April 16, 2012. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Hepatitis B information for health professionals. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/HBV/index.htm. Accessed April 16, 2012. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Hepatitis D information for health professionals. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/HDV/index.htm. Accessed April 16, 2012. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Hepatitis E information for health professionals. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/HEV/index.htm. Accessed April 16, 2012. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Viral hepatitis C: fact sheet. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/HCV/index.htm. Accessed April 16, 2012. Hasse JM, Matarese LE. Medical nutrition therapy for hepatobiliary and pancreatic disorders. In: Mahan LK, Escott-Stump S, Raymond JL. Krause’s Food and the Nutrition Care Process. 13th ed. St Louis, MO: Saunders Elsevier; 2012:645-674. Liver Transplant Program and Center for Liver Disease, University of Southern California, Dept of Surgery. Current therapy of chronic viral hepatitis. Available at: http://www.surgery.usc.edu/divisions/hep/livernewslettercurrenttherapyofchronicviralhepatitis.html. Accessed April 16, 2012. Richardson RA, Davidson HI, Hinds A, Cowans S, Rae R, Garden OJ. Am J Clin Nutr [serial online]. 1999;69:331-337. Influence of the metabolic sequelae of liver cirrhosis on nutritional intake. Available at: http://www.ajcn.org/cgi/content/full/69/2/331. Accessed April 16, 2012. Review Date 4/12 G-0617