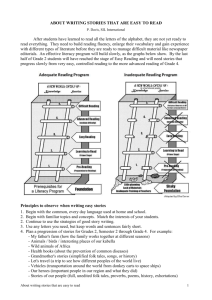

Evolution and Cognitive Development

advertisement