Society for Neuroscience

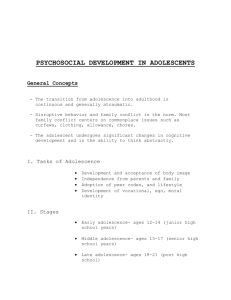

advertisement

Society for Neuroscience Article “Young Brains on Alcohol” http://www.sfn.org/index.cfm?pagename=brainBriefings_youngBrainsOnAlcohol As you read the following articles, think about the claim made below by the author. As you read, take notes that provide evidence to support his claim on the left and an interpretation of that evidence on the right. Claim: “Clearly, experimentation with alcohol during youth is bad news. But now research shows it's even worse than you think. Recent studies suggest that drinking harms the developing brains of adolescents and teens possibly even more than it does adults. The repercussions may include learning and memory problems, among others. If confirmed, the results provide additional evidence that young people should avoid alcohol.” Evidence: Examples, quotes, textural references that support the claim… Interpretation: An explanation and/or analysis of the evidence. . . Society for Neuroscience The Adolescent Brain Scientists once thought the brain's key development ended within the first few years of life. Current findings, however, indicate that important brain regions undergo refinement through adolescence and at least into a person's twenties. Thanks to advanced brain imaging techniquest, scientists now can map brain tissue growth spurts and losses, allowing researchers to compare brain growth in both health and disease and to pinpoint where brain changes are most prominent in disease. Already brain mapping research is underway for diseases that often emerge in adolescence, including schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. From this research, more targeted interventions are likely to be developed and administered early to treat or prevent ensuing disorders. Teenagers and adults often don't see eye to eye, but new brain research is shedding light on why. Although adolescence is often characterized by increased independence and a desire for knowledge and exploration, it is also a time when brain changes can result in high-risk behaviors, addiction vulnerability, and mental illness, as different parts of the brain mature at different rates. Many teens, for example, use adolescence as a time to experiment with drugs. A 2004 study found that 70 percent of high school seniors used alcohol in the previous year. What's more, the adolescent's brain may be particularly vulnerable to the negative effects of drugs, including becoming addicted later in life more so than people who don't use drugs before age 21. Atypical brain changes and behaviors also can appear in adolescence. A 2005 report found that an estimated 2.7 million children and adolescents are reported by their parents to suffer from severe emotional or behavioral difficulties. These difficulties may persist throughout development and lead to lifelong disability, including more serious and co-occurring mental illnesses. Scientists once thought the brain's key development ended within the first few years of life. Now, thanks to advanced brain imaging technology and adolescent research, scientists are learning more about the teenage brain both in health and in disease. They know now that the brain continues to develop at least into a person's twenties. What's more, these findings are starting to lead to earlier and more targeted treatments for diseases that begin with abnormal brain changes in adolescence or earlier. Advances in adolescent brain research are leading to: • A better understanding of the growing adolescent brain, both in typical and atypical development. • Earlier detection of atypical brain changes that may serve as markers for diseases or disorders later in life. • Improved and targeted interventions that can be administered early enough to potentially prevent the development of more serious illness. During adolescence, brain connections and signaling mechanisms selectively change over time to meet the needs of the environment. Overall, gray matter volume increases at earlier ages, followed by sustained loss and thinning starting around puberty, which correlates with advancing cognitive abilities. Scientists think this process reflects greater organization of the brain as it prunes redundant connections, and increases in myelin, which enhance transmission of brain messages. Other parts of the brain also undergo refinement during the teen years. Areas associated with more basic functions, including the motor and sensory areas, mature early. Areas involved in planning and decision-making, including the prefrontal cortex -- the cognitive or reasoning area of the brain important for controlling impulses and emotions -- appear not to have yet reached adult dimension during the early twenties. The brain's reward center, the ventral striatum, also is more active during adolescence than in adulthood, and the adolescent brain still is strengthening connections between its reasoning- and emotion-related regions. Scientists believe these collective findings may indicate that cognitive control over highrisk behaviors is still maturing during adolescence, making teens more apt to engage in risky behaviors. Also, with the brain's emotion-related areas and connections still maturing, adolescents may be more vulnerable to psychological disorders. Current research is looking at the manifestations of psychological disorders in adolescents, particularly schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Large imaging studies have shown that brain changes associated with schizophrenia typically begin in adolescence when the brain undergoes the normal pruning sequence of myelination growth spurts and gray matter loss. It appears that a larger and more severe wave of gray matter loss occurs in the brains of adolescents developing schizophrenia, which eventually engulfs much of the cortex after a period of five years. Scientists believe that the natural teenage process of pruning may be accelerated or otherwise altered in schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and other neurodevelopmental disorders. This research is leading to treatment implications, including a newer antipsychotic medication that, if administered early, may prevent or slow the severe wave of gray matter loss in schizophrenia and keep the disorder from progressing. Scientists also are exploring the use of low doses of medication to prevent the functional alterations in brain cells in bipolar disorder. Appendix #12b The above composite MRI brain images show top views of the sequence of gray matter maturation over the surface of the brain. Researchers found that, overall, gray matter volume increased at earlier ages, followed by sustained loss and thinning starting around puberty, which correlates with advancing cognitive abilities. Scientists think this process reflects greater organization of the brain as it prunes redundant connections, and increases in myelin, which enhance transmission of brain messages. Society for Neuroscience Young Brains on Alcohol http://www.sfn.org/index.cfm?pagename=brainBriefings_youngBrainsOnAlcohol Clearly, experimentation with alcohol during youth is bad news. But now research shows it's even worse than you think. Recent studies suggest that drinking harms the developing brains of adolescents and teens possibly even more than it does adults. The repercussions may include learning and memory problems, among others. If confirmed, the results provide additional evidence that young people should avoid alcohol. Acting like a fool, vomiting and a day-after headache are a few common side effects. More seriously, it may lead to an arrest or, in excess amounts, spur an accidental injury, even death. Yet many young people consume alcohol. Approximately 9.7 million Americans aged 12 to 20 reported drinking alcohol in the month prior to a recent survey by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Converging lines of research, however, now provide additional evidence that the young should steer clear of beer, wine and other alcoholic beverages. Although the work is still in an early stage, it appears that drinking can launch a damaging brain assault in teens and adolescents that may even surpass its effects in adults. The new research is leading to: Insights into the sensitive brain development patterns of youth. A clearer understanding of the biological and mental effects of alcohol. Increased interest in alcohol prevention programs. Findings on brain development provided some of the first clues that young brains may be more vulnerable to alcohol than adults. Researchers thought that the brain's key development finished within the first few years of life. Then recently they discovered that important brain regions continue to undergo refinement at least into a person's early twenties. For example, one study compared the brain structure of kids aged 12 to 16 with young adults aged 23 to 30. Several brain areas showed signs that their circuits pare down and fine tune between adolescence and young adulthood. Included is the frontal cortex,which helps process highly complex information. Another study examined molecular changes in the memory brain area, known as the hippocampus, and found that it is still maturing in rats equivalent in age to human teenagers. The findings imply that introducing alcohol during this developmental stage can potentially harm the growing system and associated brain functions, such as learning and memory. Several, more specific studies, back this idea. In one report, the equivalent of about five drinks in people impairs the ability of adolescent rats, but not adults, to learn a memory task. Other research examined two molecular processes tied to memory, termed long-term potentiation and Nmethyl-D-aspartate receptor activity. Adolescent rats that received the equivalent of about one to two drinks experience more interference with these processes than do adults. Perhaps most troublesome is work suggesting long-lasting alterations. One study found that the equivalent of about 10 drinks produces more extensive brain damage in adolescent rats than in adults. Findings are hard to confirm in humans because scientists can't provide underage children with alcohol and then dissect their brains. Some evidence, however, is in line with the animal work. For example, a study of young people indicates that those who start drinking during adolescence have smaller hippocampal memory areas than non-drinkers. Another study finds that following the consumption of about two to three drinks, people in their early twenties perform worse on memory tests than people in their late twenties. More recently researchers examined subjects aged 18 to 25 who reported a history of drinking about a six-pack on weekend nights. Compared with non-drinkers, they perform somewhat worse on memory tasks. Furthermore, their performance correlates with poor brain activity. Preliminary findings show similar results with younger teens who drink heavily (see images). Their brain response is also diminished, although they manage to perform okay on the tasks. The researchers plan to investigate further how various drinking histories affect different age groups. Some scientists also believe that the immature young brain may put kids at a disadvantage when they encounter situations involving alcohol. Possibly, their brains can't provide the foresight that they should avoid drinking because it's dangerous. Also, once experimentation begins, brain areas that make a person feel good and want to drink again may be in an underdeveloped state and more easily influenced. Overall, the research adds fire to an often-repeated message: Just say no. The brain images below show how alcohol may harm teen mental function. Compared with a young non-drinker, a 15-year-old with an alcohol problem showed poor brain activity during a memory task. This finding is noted by the lack of pink and red coloring. Image from Susan Tapert, PhD, University of California, San Diego.