Chapter 14 Microbial Evolution and Systematics

advertisement

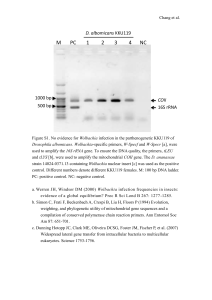

세균학 강의자료 (1) Chapter 14 Microbial Evolution and Systematics I. Early Earth and the Origin and Diversification of Life 14.1 Formation and Early History of Earth The Earth is ~ 4.5 billion years old First evidence for microbial life can be found in rocks ~ 3.86 billion years old Stromatolites Fossilized microbial mats consisting of layers of filamentous prokaryotes and trapped sediment Found in rocks 3.5 billion years old or younger Comparisons of ancient and modern stromatolites provide evidence that Anoxygenic phototrophic filamentous bacteria formed ancient stromatolites Oxygenic phototrophic cyanobacteria dominate modern stromatolites 14.2 Origin of Cellular Life Early Earth was anoxic and much hotter than present day First biochemical compounds were made by abiotic systems that set the stage for the origin of life Surface Origin Hypothesis Contends that the first membrane-enclosed, self-replicating cells arose out of primordial soup rich in organic and inorganic compounds in ponds on Earth’s surface Dramatic temperature fluctuations and mixing from meteor impacts, dust clouds, and storms argue against this hypothesis States that life originated at hydrothermal springs on ocean floor Conditions would have been more stable Steady and abundant supply of energy (e.g., H2 and H2S) may have been available at these sites Prebiotic chemistry of early Earth set stage for self-replicating systems First self-replicating systems may have been RNA-based (RNA world theory) RNA can bind small molecules (e.g., ATP, other nucleotides) RNA has catalytic activity; may have catalyzed its own synthesis 1 DNA, a more stable molecule, eventually became the genetic repository Three-part systems (DNA, RNA, and protein) evolved and became universal among cells Other Important Steps in Emergence of Cellular Life Build up of lipids Synthesis of phospholipid membrane vesicles that enclosed the cell’s biochemical and replication machinery May have been similar to montmorillonite clay vesicles Last Universal Common Ancestor (LUCA) Population of early cells from which cellular life may have diverged into ancestors of modern day Bacteria and Archaea As early Earth was anoxic, energy-generating metabolism of primitive cells was exclusively Anaerobic and likely chemolithotrophic (autotrophic) Obtained carbon from CO2 Obtained energy from H2; likely generated by H2S reacting with H2S or UV light Early forms of chemolithotrophic metabolism would have supported production of large amounts of organic compounds Organic material provided abundant, diverse, and continually renewed source of reduced organic carbon, stimulating evolution of various chemoorganotrophic metabolisms 14.3 Microbial Diversification Molecular evidence suggests ancestors of Bacteria and Archaea diverged ~ 4 billion years ago As lineages diverged, distinct metabolisms developed Development of oxygenic photosynthesis dramatically changed course of evolution ~ 2.7 billion years ago, cyanobacterial lineages developed a photosystem that could use H2O instead of H2S, generating O2 By 2.4 billion years ago, O2 concentrations raised to 1 part per million; initiation of the Great Oxidation Event O2 could not accumulate until it reacted with abundant reduced materials in the oceans (i.e., FeS, FeS2) Banded iron formations: laminated sedimentary rocks; prominent feature in geological record 2 Development of oxic atmosphere led to evolution of new metabolic pathways that yielded more energy than anaerobic metabolisms Oxygen also spurred evolution of organelle-containing eukaryotic microorganisms Oldest eukaryotic microfossils ~ 2 billion years old Fossils of multicellular and more complex eukaryotes are found in rocks 1.9 to 1.4 billion years old Consequence of O2 for the evolution of life Formation of ozone layer that provides a barrier against UV radiation Without this ozone shield, life would only have continued beneath ocean surface and in protected terrestrial environments 14.4 Endosymbiotic Origin of Eukaryotes Endosymbiosis Well-supported hypothesis for origin of eukaryotic cells Contends that mitochondria and chloroplasts arose from symbiotic association of prokaryotes within another type of cell Two hypotheses exist to explain the formation of the eukaryotic cell 1) Eukaryotes began as nucleus-bearing lineage that later acquired mitochondria and chloroplasts by endosymbiosis 2) Eukaryotic cell arose from intracellular association between O2-consuming bacterium (the symbiont), which gave rise to mitochondria and an archaean host Both hypotheses suggest eukaryotic cell is chimeric This is supported by several features Eukaryotes have similar lipids and energy metabolisms to bacteria Eukaryotes have transcription and translational machinery most similar to archaea II. Microbial Evolution 14.5 The Evolutionary Process Mutations Changes in the nucleotide sequence of an organism’s genome Occur because of errors in the fidelity of replication, UV radiation, and other factors Adaptative mutations improve fitness of an organism, increasing its survival Other genetic changes include gene duplication, horizontal gene transfer, and gene loss 3 14.6 Evolutionary Analysis: Theoretical Aspects Phylogeny Evolutionary history of a group of organisms Inferred indirectly from nucleotide sequence data Molecular clocks (chronometers) Certain genes and proteins that are measures of evolutionary change Major assumptions of this approach are that nucleotide changes occur at a constant rate, are generally neutral, and random The most widely used molecular clocks are small subunit ribosomal RNA (SSU rRNA) genes Found in all domains of life 16S rRNA in prokaryotes and 18S rRNA in eukaryotes Functionally constant Sufficiently conserved (change slowly) Sufficient length Carl Woese Pioneered the use of SSU rRNA for phylogenetic studies in 1970s Established the presence of three domains of life: Bacteria, Archaea, and Eukarya Provided a unified phylogenetic framework for Bacteria The Ribosomal Database Project (RDP) A large collection of rRNA sequences Currently contains > 409,000 sequences Provides a variety of analytical programs 14.7 Evolutionary Analysis: Analytical Methods Comparative rRNA sequencing is a routine procedure that involves Amplification of the gene encoding SSU rRNA Sequencing of the amplified gene Analysis of sequence in reference to other sequences The first step in sequence analysis involves aligning the sequence of interest with sequences from homologous (orthologous) genes from other strains or species BLAST (Basic Local Alignment Search Tool) Web-based tool of the National Institutes of Health Aligns query sequences with those in GenBank database Helpful in identifying gene sequences 4 Phylogenetic Tree Graphic illustration of the relationships among sequences Composed of nodes and branches Branches define the order of descent and ancestry of the nodes Branch length represents the number of changes that have occurred along that branch Evolutionary analysis uses character-state methods (cladistics) for tree reconstruction Cladistic methods Define phylogenetic relationships by examining changes in nucleotides at individual positions in the sequence Use those characters that are phylogenetically informative and define monophyletic groups Common cladistic methods Parsimony Maximum likelihood Bayesian analysis 14.8 Microbial Phylogeny The universal phylogenetic tree based on SSU rRNA genes is a genealogy of all life on Earth Domain Bacteria Contains at least 80 major evolutionary groups (phyla) Many groups defined from environmental sequences alone I.e., no cultured representatives Many groups are phenotypically diverse I.e., physiology and phylogeny not necessarily linked Eukaryotic organelles originated within Bacteria Mitochondria arose from Proteobacteria Chloroplasts arose from the cyanobacterial phylum Domain Archaea consists of two major groups Crenarchaeota Euryarchaeota Each of the three domains of life can be characterized by various phenotypic properties 5 14.9 Applications of SSU rRNA Phylogenetic Methods Signature Sequences Short oligonucleotides unique to certain groups of organisms Often used to design specific nucleic acid probes Probes Can be general or specific Can be labeled with fluorescent tags and hybridized to rRNA in ribosomes within cells FISH: fluorescent in situ hybridization Circumvent need to cultivate organism(s) PCR can be used to amplify SSU rRNA genes from members of a microbial community Genes can be sorted out, sequenced, and analyzed Such approaches have revealed key features of microbial community structure and microbial interactions Ribotyping Method of identifying microbes from analysis of DNA fragments generated from restriction enzyme digestion of genes encoding SSU rRNA Highly specific and rapid Used in bacterial identification in clinical diagnostics and microbial analyses of food, water, and beverage III. Microbial Systematics 14.10 Phenotypic Analysis Taxonomy The science of identification, classification, and nomenclature Systematics The study of the diversity of organisms and their relationships Links phylogeny with taxonomy Bacterial taxonomy incorporates multiple methods for identification and description of new species The polyphasic approach to taxonomy uses three methods 1) Phenotypic analysis 2) Genotypic analysis 3) Phylogenetic analysis Phenotypic analysis examines the morphological, metabolic, physiological, and chemical characters of the cell 6 Fatty Acid Analyses (FAME: fatty acid methyl ester) Relies on variation in type and proportion of fatty acids present in membrane lipids for specific prokaryotic groups Requires rigid standardization because FAME profiles can vary as a function of temperature, growth phase, and growth medium 14.11 Genotypic Analysis Several methods of genotypic analysis are available and used DNA-DNA hybridization DNA profiling Multilocus Sequence Typing (MLST) GC Ratio DNA-DNA hybridization Genomes of two organisms are hybridized to examine proportion of similarities in their gene sequences Provides rough index of similarity between two organisms Useful complement to SSU rRNA gene sequencing Useful for differentiating very similar organisms Hybridization values 70% or higher suggest strains belong to the same species Values of at least 25% suggest same genus DNA Profiling Several methods can be used to generate DNA fragment patterns for analysis of genotypic similarity among strains, including Ribotyping: focuses on a single gene Repetitive extragenic palindromic PCR (rep-PCR) and Amplified fragment length polymorphism (AFLP): focus on many genes Multilocus Sequence Typing (MLST) Method in which several different “housekeeping genes” from an organism are sequenced Has sufficient resolving power to distinguish between very closely related strains GC Ratios Percentage of guanine plus cytosine in an organism’s genomic DNA Vary between 20 and 80% among Bacteria and Archaea Generally accepted that if GC ratios of two strains differ by ~ 5% they are unlikely to be closely related 7 14.12 Phylogenetic Analysis 16S rRNA gene sequences are useful in taxonomy; serve as “gold standard” for the identification and description of new species Proposed that a bacterium should be considered a new species if its 16S rRNA gene sequence differs by more than 3% from any named strain, and a new genus if it differs by more than 5% The lack of divergence of the 16S rRNA gene limits its effectiveness in discriminating between bacteria at the species level, thus, a multi-gene approach can be used Multi-gene sequence analysis is similar to MLST, but uses complete sequences and comparisons are made using cladistic methods Whole-genome sequence analyses are becoming more common Genome structure; size and number of chromosomes, GC ratio, etc. Gene content Gene order No universally accepted concept of species for prokaryotes Current definition of prokaryotic species Collection of strains sharing a high degree of similarity in several independent traits Most important traits include 70% or greater DNA-DNA hybridization and 97% or greater 16S rRNA gene sequence identity Biological species concept not meaningful for prokaryotes as they are haploid and do not undergo sexual reproduction Genealogical species concept is an alternative Prokaryotic species is a group of strains that based on DNA sequences of multiple genes cluster closely with others phylogenetically and are distinct from other groups of strains Ecotype Population of cells that share a particular resource Different ecotypes can coexist in a habitat Bacterial speciation may occur from a combination of repeated periodic selection for a favorable trait within an ecotype and lateral gene flow This model is based solely on the assumption of vertical gene flow New genetic capabilities can also arise by horizontal gene transfer; the extent among bacteria is variable No firm estimate on the number of prokaryotic species Nearly 7,000 species of Bacteria and Archaea are presently known 8 14.14 Classification and Nomenclature Classification Organization of organisms into progressively more inclusive groups on the basis of either phenotypic similarity or evolutionary relationship Prokaryotes are given descriptive genus names and species epithets following the binomial system of nomenclature used throughout biology Assignment of names for species and higher groups of prokaryotes is regulated by the Bacteriological Code The International Code of Nomenclature of Bacteria Major references in bacterial diversity Bergey’s Manual of Systematic Bacteriology The Prokaryotes Formal recognition of a new prokaryotic species requires Deposition of a sample of the organism in two culture collections Official publication of the new species name and description in the International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology (IJSEM) The International Committee on Systematics of Prokaryotes (ICSP) is responsible for overseeing nomenclature and taxonomy of Bacteria and Archaea 9