Case Studies in Recruiting and Employing Physicians

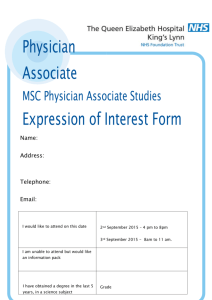

advertisement

Case Studies in Recruiting and Employing Physicians: Can We Do This? Prepared for: Region VII HCCA Compliance Conference August 1, 2003 Westin Crown Center Kansas City, Missouri By: Julie A. Knutson, J.D. of Baird, Holm, McEachen, Pedersen, Hamann & Strasheim LLP 1500 Woodmen Tower Omaha, Nebraska 68102 402-636-8327 jknutson@bairdholm.com © 2003 Baird, Holm, McEachen, Pedersen, Hamann & Strasheim LLP EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Financial incentives play an important role for community hospitals that wish to recruit or retain physicians. However, recruitment incentives subject hospitals to liability under federal laws governing unlawful referrals and kickbacks. Nonprofit hospitals are further subject to the IRS regulations for tax-exempt organizations. 1. Tax-Exempt Issues. A private, nonprofit hospital that is tax-exempt under section 501(c)(3) of the Internal Revenue Code must be cognizant of the fact that the recruitment and compensation packages offered by the hospital could jeopardize the organization’s tax-exempt status if they are not reasonable or if they result in inurement or excess private benefit. The applicable rules prohibit exempt organizations from using charitable money to benefit private individuals unless the private benefit is merely incidental to the public benefit derived from the charitable activity. Violators of this private inurement rule are subject to immediate sanctions involving taxes and penalties. 2. Anti-Kickback Statute. The Federal Anti-Kickback Statute prohibits direct or indirect payment of remuneration with the intent to receive referrals. A violation is a felony, punishable by fines and imprisonment, although a violation may also result in exclusion from the Medicare and Medicaid program. The anti-kickback law contains several safe harbors which limit the potentially broad reach of the statute. Failure to fall within a safe harbor does not mean that the statute is violated per se, but the arrangement will be subject to a factual review including fair market value and an analysis of intent. Safe Harbors: Recognizing the need to attract physicians to rural area hospitals, a safe harbor was developed to allow the recruitment of physicians in specialty areas by means that might otherwise violate the statute. This physician recruitment safe harbor is not all-encompassing as specific conditions must be met, including the requirement that a majority of the physician’s revenue come from new patients who reside in a health professional shortage area. In addition, there is a statutory exception for compensation paid under a bona fide employment arrangement. 3. Stark. The Ethics in Patient Referral Act (generally known as Stark) further prohibits physicians who have a financial relationship with an entity from ordering or referring patients to the entity for any “designated health service” paid by Medicare and Medicaid unless an exception exists. Penalties for violations include refusal of payment for any related claim and possible False Claims Act liability. Under Stark, it is imperative that any transaction involving a financial relationship between the physician and the hospital be covered by an exception since a Stark violation, unlike a violation of the anti-kickback law, is not affected by intent. Exceptions: One exception for physician recruitment requires the physician to relocate his or her practice in order to become a member of the hospital’s © 2003 Baird, Holm, McEachen, Pedersen, Hamann & Strasheim LLP medical staff. Another exception for employment allows a productivity bonus arrangement if it is based on services performed personally by the physician and such bonus is not directly related to the volume or value of the physician’s own referrals. Given the multiple regulations governing physician recruitment and employment, it is important to understand that a physician recruitment arrangement that complies with the requirements for maintaining tax-exempt status may violate the anti-kickback or Stark self-referral laws. Despite this lack of uniformity among the regulations, the IRS and OIG rulings and opinions have clarified and set forth general guidelines for compliance. Accordingly, the general rule as it pertains to physician recruiting and employment is that hospitals may expend reasonable funds to recruit needed health care practitioners to a community, particularly in medically underserved areas. Specifically, a hospital should be concerned with the following matters: Maintaining the hospital’s tax exempt status by ensuring the manner and method for computing the recruited physician’s incentive and compensation packages do not subject the organization to intermediate sanctions or jeopardize exemption. Avoiding any violation of the anti-kickback rules by ensuring that recruitment incentives or packages are not prohibited remuneration intended to induce referrals of Medicare or Medicaid business to the hospital. Ensuring the financial relationship created by payment of recruitment incentives falls under an exception to the Stark (Ethics in Patient Referral) Act. © 2003 Baird, Holm, McEachen, Pedersen, Hamann & Strasheim LLP 2 LEGAL PARAMETERS FOR PHYSICIAN RECRUITMENT The following summarizes the legal authorities governing physician recruiting in private, nonprofit hospitals tax-exempt under section 501(c)(3) of the Internal Revenue Code. The general rule is that hospitals and other nonprofit/tax-exempt community organizations may expend reasonable funds to recruit needed health care practitioners to a community, particularly in medically underserved areas. The primary legal considerations are: I. Maintaining the hospital’s tax exempt status by making certain that the amount of recruitment incentives and the manner in which such incentives are furnished do not provide grounds for intermediate sanctions or jeopardize exemption. Avoiding any violation of Medicare Fraud and Abuse (anti-kickback) rules by assuring that recruitment incentives are not prohibited remuneration designed to induce referrals of Medicare or Medicaid business to the hospital. Qualifying any financial relationship created by payment of recruitment incentives under an exception to the Stark (Ethics in Patient Referral) Act. In the case of public hospitals, avoiding violation of the powers of the public hospital under state law. IRS Issues. Three relatively recent sources of guidance from the IRS and Treasury Department provide specific insight into IRS physician recruitment standards, particularly in the context of recruiting nonemployee physicians. Of these sources, however, only Rev. Rul. 97-21 constitutes binding authority. A. Internal Revenue Manual Audit Guidelines. Although these audit guidelines are no longer current, they still have instructive value with respect to factors that the auditor should consider in investigating the reasonableness of the recruiting activities of a hospital under audit. The audit guidelines suggest that auditors be on the alert for any of the following arrangements: 1. Physicians being charged no rent or below-market rent for space in hospital-owned office buildings; 2. Hospitals guarantees; providing physicians with private practice income 3. Hospitals providing financial assistance to physicians for home purchases and/or the purchase of office equipment; and 4. Outright cash payments by hospitals to physicians to secure or retain their services. © 2003 Baird, Holm, McEachen, Pedersen, Hamann & Strasheim LLP 3 Although none of the above-described arrangements are prohibited per se, they have been viewed by the IRS as potential areas of abuse and are scrutinized closely during audits. The Hospital Audit Guidelines further provided that, in order to establish that any loans, income guarantees or other subsidies used as recruiting incentives further charitable purposes and are reasonable, the specialist must be able to determine that there is a need for the physician in the community served by the hospital. “Absent evidence of a compelling community need or a significant other benefit to the community, the recruitment contract should require full repayment (at prevailing interest rates). Evidence of need may include the previous absence of practitioners in a given specialty, government studies of health manpower, patient travel patterns, etc.” Id. at 333.3(4). The IRS Hospital Audit Guidelines acknowledged the reasonableness of guarantees of private practice income under certain circumstances: Income is guaranteed for a one- or two-year period; The physician is relocating his or her practice to the hospital’s service area; There is sufficient evidence of need for the physician in the community; The level of income guaranteed is reasonable; There is a reasonable and explicit ceiling on total outlays by the hospital; There is an unconditional obligation to repay any amounts advanced by the hospital; and Any forgiveness is demonstrably related to community benefit and treated as compensation. B. Hermann Hospital Closing Agreement. In the closing agreement entered between Hermann Hospital of Houston, Texas, and the IRS on September 16, 1994, Hermann Hospital was required to adopt a number of specific hospital-physician recruitment guidelines developed by the IRS as a condition to maintaining its tax-exempt status. (The closing agreement was also conditioned on a payment of approximately $1,000,000 by the hospital to the IRS.) Although these requirements are specifically applicable only to Hermann Hospital, and other hospitals are not bound by the closing agreement, they are indicative of the IRS position with respect to justification of physician recruiting incentives. 1. Public Benefit Requirements. The closing agreement set out six examples of conditions, one or more of which must apply in order for Hermann Hospital to pay recruiting incentives based on public benefit: © 2003 Baird, Holm, McEachen, Pedersen, Hamann & Strasheim LLP 4 a. A population-to-physician ratio in the community deficient in the relevant specialty relative to the ideal ratio contained in Graduate Medical Education National Advisory Committee (GMENAC) reports; b. Demand for a particular health service in the community for which the physician is being recruited, coupled with the documented lack of availability of the service or long waiting periods; c. Designation of the community or area where the physician will serve when the agreement is executed, as a Health Professional Shortage Area as defined in Sections 5.1 through 5.4 of Title 42 of the Code of Federal Regulations; d. A demonstrated reluctance of physicians to relocate to the hospital due to the hospital’s physical location (intended to refer to a hospital in a rural or economically disadvantaged inner city area); e. A reasonably expected reduction in the number of physicians in the relevant specialty in the service area due to anticipated retirements during the next three years; or f. A documented lack of physicians serving indigent or Medicaid patients within the service area, provided the recruit commits to serving a “substantial number” of Medicaid and charity care patients. 2. Income Guaranties. The closing agreement with Hermann Hospital permitted income guaranties, but specified that: a. The guaranty must be limited to a two-year period with no modifications. b. Certain additional incentives were prohibited, presumably because when added to the income guaranty, the overall level of incentives was no longer reasonable. c. Any advances must be treated as a loan with a reasonable market rate of interest, with forgiveness tied to at least four years of continuing community services. d. There must be a ceiling on the total amount of advances. e. The total incentive package must be reasonable. f. The recruited physician must permit the hospital to inspect his or her financial records. C. Revenue Ruling 97-21. On April 21, 1997, the IRS released Rev. Rul. 9721, which restates IRS Announcement 95-25 with some revisions. The © 2003 Baird, Holm, McEachen, Pedersen, Hamann & Strasheim LLP 5 release of Rev. Rul. 97-21 is significant because revenue rulings are precedential authority and because the revenue ruling is somewhat more liberal than other recent guidance. The revenue ruling contains the following five situations: 1. Situation #1: Rural hospital recruitment of recent OB-GYN graduate. Located in Health Professional Shortage Area. Only hospital in 100-mile radius. Signing bonus, malpractice premium for a limited period, office space for a limited period at a below-market rent, guarantee of personal residence mortgage, loan for start-up on reasonable terms. 2. Situation #2: Inner city hospital recruitment of out-of-area pediatrician to establish a practice and treat a reasonable number of Medicaid patients. Medicaid patients having difficulty obtaining pediatric services. Reimbursement for moving expenses, reimbursement for tail coverage for prior practice, net income guarantee for a limited number of years. 3. Situation #3: Inner city hospital recruitment of an existing member of its medical staff to provide obstetrical care to Medicaid and indigent patients. Medicaid and indigent patients do not have access to OB care. Reimbursement of one year’s malpractice premium in return for an agreement to treat a reasonable number of Medicaid and indigent patients. 4. Situation #4: Metropolitan area hospital recruitment of a diagnostic radiologist from another hospital in the same area. Hospital needs four radiologists; two have recently left. One of the most qualified candidates is at an area hospital. Net income guarantee for first few years. 5. Situation #5: Metropolitan area hospital whose recruiting activities resulted in conviction of a hospital for violation of the anti-kickback law because recruiting payments were payments for referrals. The fact situation approach is similar to a 1969 hospital revenue ruling. The first four situations were found not to violate Section 501(c)(3) standards. The fifth situation (in which kickback violations were found) was held to violate such standards. In connection with a showing of community need, this ruling appears to require either presence in a medically underserved area or a study showing needs in particular specialties. This ruling does not address physician retention programs and none of the situations deal with recruitment into an existing practice. There is no specification of fixed time periods for recruiting incentives; all refer to a “limited period of time.” The income guarantees in these situations did not require paybacks. In all situations, the incentives were approved in accordance with the formal board policy or with specific board approval. The factual assumption by the IRS in each of the situations is that none of the physicians are insiders or disqualified persons, and that they do not have substantial influence over the affairs of the hospital that recruited them. Intermediate sanctions are not specifically © 2003 Baird, Holm, McEachen, Pedersen, Hamann & Strasheim LLP 6 addressed by the ruling but are clearly applicable if there are excess benefit transactions. The IRS describes the nature of the community benefit resulting from recruitment as follows: “The community benefit to which the recruitment incentive is compared is the value of the physician to the community. For example, a determination that the physician enhances the productivity of the hospital (other than by simply referring patients), provides a new service or brings a needed specialty to the community are indicative of community benefit that may justify a reasonable recruitment incentive. To demonstrate a need in the community for a particular physician’s services, the hospital should document such indicators as the previous absence of practitioners in a given specialty, governmental studies of health manpower, or patient travel patterns.” D. IRS Information Letter 2002-0021 dated March 29, 2002. A letter from the manager of the IRS Exempt Organizations Technical Group 1 addressed the ability of nonprofit hospitals to offer incentive payments to physicians on staff at such hospitals. The specific program which the letter considered involved payments to physicians who assisted the hospital in improving the efficiency of inpatient care for Medicare beneficiaries while setting forth strict standards for monitoring the quality of care. After setting forth twelve factors to be considered in determining whether an incentive program would result in private benefit or inurement which would jeopardize the hospital’s tax exempt status, the letter concluded by explaining that “there is no prohibition or per se rule that prevents health care organizations from making incentive payments to physicians.” The factors considered were: The involvement of an independent board of directors to establish the arrangement Whether the compensation is reasonable Whether the relationship between the physician and hospital is at arms length Whether there is ceiling on compensation to prohibit windfalls Whether the compensation arrangement results in a reduction of charitable services If the arrangement is net revenue based, does it still accomplish the hospital’s charitable purposes and goals Whether the arrangement transforms the hospital’s principal activity into a joint venture with the physician © 2003 Baird, Holm, McEachen, Pedersen, Hamann & Strasheim LLP 7 Whether safeguards exist to prevent the distribution of profits to those individuals in control of the hospital Whether the arrangement serves a real and discernible business purpose Whether safeguards protect the arrangement from resulting in unnecessary utilization and abuse Whether the compensation is based upon services personally performed by the physicians Although the advisory letter is not binding on the IRS, it is indicative of the factors to consider in analyzing whether incentive payments will jeopardize an organization’s tax-exempt status. II. INTERMEDIATE SANCTIONS. A. Statutory Terms. 26 CFR Section 53.4958-1 imposes an excise tax on a disqualified person who is a party to an excess benefit transaction with a taxexempt organization. B. Excise Taxes. 1. Initial 25% tax on excess benefit to disqualified person. 2. Initial tax of 10% (up to $10,000) on organization managers who participated in the transaction knowing it to be an excess benefit transaction. 3. Additional tax of 200% on the disqualified person if not corrected. C. Definition of an Excess Benefit Transaction. The regulations at 26 CFR Section 53.4958-4(a) define an excess benefit transaction as any transaction “in which an economic benefit is provided by an applicable taxexempt organization directly or indirectly, to or for the use of, any disqualified person, and the value of the economic benefit provided exceeds the value of the consideration (including the performance of services) received by the organization for providing such benefit.” An economic benefit shall not be treated as consideration for the performance of services unless the organization providing the benefit clearly indicates its intent to treat the benefit as compensation when the benefit is paid. D. Rebuttable Presumption of Reasonableness. The regulations at 26 CFR Section 53.4958-6 provide that a transaction shall be presumed to be reasonable and at fair market value if three conditions are satisfied: © 2003 Baird, Holm, McEachen, Pedersen, Hamann & Strasheim LLP 8 1. Approved by the board or a board committee – Board or committee members are unrelated to and not subject to control of the disqualified person. E. 2. Obtained and relied upon appropriate data as to comparability. 3. Adequately documented the basis for its determination. Tax on Organization Managers. The statute provides that organization managers are liable for a tax of 10% of the excess benefit, unless their participation was not willful and was due to reasonable cause. The regulations state that “willful” means voluntary, conscious, and intentional. No motive to avoid the restrictions of the law or the incurrence of any tax is necessary to make the participation willful. An organization manager’s participation is due to “reasonable cause” if the manager has exercised his or her responsibility with ordinary business care and prudence. Reliance on the advice of a professional expressed in a “reasoned written opinion” that the transaction is not an excess benefit transaction will ordinarily be considered due to reasonable cause even if the transaction is later held to be an excess benefit transaction. A “reasoned written opinion” must address itself to the facts and applicable law. A written opinion is not reasoned if it does nothing more than recite the facts and express a conclusion. Professionals can include attorneys, CPA, and valuation experts. If the organization manager fails to get a reasoned written opinion, the absence of such advice does not by itself give rise to an inference that the organization manager acted without reasonable cause. III. Medicare Fraud and Abuse (Anti-Kickback) Issues. The anti-kickback statute prohibits payment of remuneration by a hospital to a physician with the intent to induce the physician to make referrals to or order services from the hospital. Since a by-product of a hospital’s recruitment of physicians is that the physician will likely refer or admit patients to the hospital, analysis of this statute is important. The courts have held that if “a” purpose of an arrangement is to induce such referrals, then the statute has been violated. With respect to physician recruitment and employment, the following authority exists: A. Statutory Exception. A statutory exception (not a safe harbor) exists for payments made by an employer to compensate an employee pursuant to a bona fide employment relationship with respect to covered services. This exception would only shield bona fide compensation; it would not shield asset purchases or payments for other than employee compensation. No showing of fair market value is required. This statutory exception has been carried forward into a safe harbor for any amount paid by an employer to an employee, who has a bona fide employment relationship with the employer for employment in the furnishing of any item or service for which © 2003 Baird, Holm, McEachen, Pedersen, Hamann & Strasheim LLP 9 payment may be made in whole or in part under Medicare or a state health care program. This exception does not specifically require that the compensation paid employees is reasonable. All that is required is that it be paid pursuant to a bona fide employment relationship. B. Safe Harbor for Physician Recruitment. Because of the potentially broad reach of the statute, Congress directed the Secretary to develop safe harbors. Due to the recognized difficulty of rural areas in attracting needed physicians, the OIG proposed a safe harbor for rural areas in September 1993. This was promulgated in final form on November 19, 1999. While the proposed safe harbor extended to any rural area (defined as any geographic area that is not a metropolitan statistical area), the final safe harbor extends only to recruitment of a physician in a HPSA for the physician’s specialty area, as defined by Departmental regulations. The safe harbor is aimed at only two types of health care providers: a practitioner relocating to a new area and a practitioner who has been practicing within his or her specialty for less than one year. To fall within the safe harbor, all of the following requirements must be met: 1. The agreement must be in writing and must specify the benefits provided by the hospital, the terms under which the benefits are be to provided and the obligations of each party. 2. If a physician is leaving an established practice, at least 75% of the revenues of the new practice must be generated from new patients not previously seen by the physician at his or her former practice. 3. The benefits provided by the hospital must not extend over more than three years, and the terms of the agreement must not be renegotiated during this three-year period. 4. The agreement must not require the physician to make referrals to, be in a position to make or influence referrals to, or otherwise generate business for the hospital as a condition for receiving the benefits under the agreement. The hospital may, however, require the practitioner to maintain medical staff privileges. 5. The physician must not be restricted from establishing staff privileges at, referring any service to, or otherwise generating any business for any other facility of his or her choosing. 6. The amount or value of the benefits provided by the hospital to the physician must not vary in any manner based on the volume or value of any expected referrals to, or business otherwise generated for, the hospital by the physician for which payment may be made under Medicare or Medicaid. © 2003 Baird, Holm, McEachen, Pedersen, Hamann & Strasheim LLP 10 7. The physician must agree to treat patients receiving Medicare or Medicaid benefits. 8. At least 75% of the revenues of the new practice must be generated from patients residing in a HPSA or a Medically Underserved Area or who are part of a Medically Underserved Population, as defined by the Secretary. 9. The payment or exchange of anything of value may not directly or indirectly benefit any person (other than the practitioner being recruited) or entity in a position to make or influence referrals to the hospital. The ninth requirement of the safe harbor is relevant to so-called three-party recruitment agreements whereby recruitment incentives are extended by a hospital to recruit a physician to an existing private practice in the community. In commentary to the physician recruitment safe harbor, the OIG states: “We are aware that an increasing amount of physician recruitment is being conducted through joint arrangements between hospitals and group practices or solo practitioners. Typically these arrangements involve payments from hospitals to group practices or solo practitioners to assist the group practice or solo practitioner in recruiting a new physician. *** On the one hand, these arrangements can be an efficient and costeffective means of recruiting needed practitioners to an underserved community. Moreover, many new practitioners prefer joining an existing group practice to starting a solo practice. On the other hand, these arrangements can be used to disguise payments for referrals from the group practice or solo practice to the hospital. We are not persuaded that a safe harbor can be crafted that would protect legitimate joint recruiting arrangements of the type described above without sweeping in sham arrangements that are actually disguised payments for referrals. However, we want to make clear that joint recruitment arrangements are not necessarily illegal and must be evaluated on a case-by-case basis. Parties seeking further guidance about their joint recruitment activities may apply for an [OIG] Advisory Opinion.” 64 FR 63518, 63544. C. Special Fraud Alert. In May 1992, the OIG issued a Special Fraud Alert regarding Hospital Incentives to Physicians, which was republished in December of 1994. The alert advised that recruitment and retention incentive programs used to compensate physicians, directly or indirectly, for referring patients to the hospital are implicated by the anti-kickback statute and are not protected under existing safe harbor regulations. The OIG was careful to state that this list is not intended to be exhaustive, but, rather, is © 2003 Baird, Holm, McEachen, Pedersen, Hamann & Strasheim LLP 11 intended only “to suggest some indicators of potentially unlawful activity.” The fraud alert listed the following incentives: 1. Payment of incentives by hospital for each physician referral. 2. Use or provision of free or significantly discounted billing, nursing, or other staff services. 3. Free training for a physician’s office staff in areas such as management technique, CPT coding, and laboratory techniques. 4. Guaranties which provide that, if the physician’s income fails to reach a predetermined level, the hospital will supplement the remainder up to a certain amount. 5. Low-interest or interest-free loans or loans that may be “forgiven” if a physician refers patients (or some number of patients) to the hospital. 6. Payment of the cost of a physician’s travel and expenses for conferences. 7. Payment for a physician’s continuing education courses. 8. Coverage in a hospital’s group health insurance at an inappropriately low cost to the physician. 9. Payment for services (which may include consultations at the hospital) which require few, if any, substantive duties by the physician or payment for services in excess of fair market value. The alert concludes with a statement that financial incentive packages incorporating these or similar features may be subject to prosecution under the anti-kickback statute, if one of the purposes of the incentive is to influence the physician’s medical decisions regarding where to refer his or her patients for treatment. In addition, the fraud alert does not distinguish between incentives offered to existing physicians in the community and newly recruited physicians to the area. Although the items on the list appear to have varying potential for abuse, the OIG makes no distinction among them. While the alert is neither a regulation nor an administrative interpretation, one federal court relied in part on the alert in holding that a physician recruitment contract was void and unenforceable for illegality under the anti-kickback law. Due to the unenforceability of the contract, the court refused to require the physician to repay the money he had borrowed under the contract. See Polk County, Tex. v. Peters, 800 F. Supp. 1451 (E.D. Tex. 1992). D. Advisory Opinion. On May 10, 2001, the OIG issued an advisory opinion regarding physician recruitment that concluded that the recruitment package © 2003 Baird, Holm, McEachen, Pedersen, Hamann & Strasheim LLP 12 offered by the hospital would potentially amount to prohibited remuneration under the anti-kickback statute if the requisite intent to induce referrals of Federal health care business was present, but, under the facts presented, the OIG would not impose administrative sanctions. In the scenario presented to the OIG, the hospital was an acute care hospital in a rural area not designated as a HPSA. However, much of the hospital’s service area was designated as a medically underserved area. A needs analysis indicated a shortage of otolaryngologists and head and neck surgeons in the service area. 1. The hospital proposed to offer the following recruitment package to recruit the needed specialist: a. A loan for five years of residency with annual designated amounts and an aggregate limit, such amount to be a combination of student loan repayment assistance plus an additional stipend for educational expenses connected with his residency. The loan would accrue interest from the date of each advance, at a rate of 1% over prime, semi-annually. b. In consideration, the physician was obligated to: (1) Establish and maintain a full-time private practice within a 3-mile radius of the city served by the hospital in which to conduct the deemed specialty practice; (2) Acquire and maintain active medical staff privileges at the hospital in the desired specialty; (3) Accept patients referred by hospital’s emergency room while on-call, regardless of the patient’s ability to pay; (4) Assist the hospital in its educational programs; (5) Upon request, assist the hospital in fundraising efforts in order to promote its charitable and educational purposes; (6) Provide reasonable assistance to the hospital in its physician recruitment program; and (7) Agree to treat patients receiving medical benefits or assistance under any Federal health care program in a nondiscriminatory manner. c. Under the recruitment agreement, the physician would repay the loan, with accrued interest, in three annual payments, beginning at the end of the residency program. Concurrently, the hospital would © 2003 Baird, Holm, McEachen, Pedersen, Hamann & Strasheim LLP 13 forgive each year’s loan provided that the physician fulfilled all obligations. d. Although the arrangement did not meet the requirements of the recruitment safe harbor (no HPSA, benefit period exceeded three years), there were no sanctions based on the following findings by the OIG: (1) Need for the physician was supported by objective study; (2) The practitioner did not have an existing stream of referrals from within the hospital’s service area; (3) The recruitment incentives were narrowly tailored so as not to exceed that necessary to recruit the practitioner; and (4) The recruitment benefits did not directly or indirectly benefit other referral sources. (Here, the OIG emphasized that “joint” or three-party recruitment agreements involving a local medical practice are subject to a higher degree of scrutiny.) E. OIG Letter Addressing Malpractice Insurance Assistance. In a letter dated January 15, 2003, the OIG responded to a request for confirmation that the implementation of an arrangement to assist in the payment of malpractice premium subsidies would not be viewed as a violation of the anti-kickback or Stark statutes. While 42 CFR Section 1001.952(o) provides a safe harbor for malpractice premium subsidies provided to persons providing obstetrical care in primary health care shortage areas, there is no general safe harbor for malpractice premiums. Noting that the malpractice insurance rates in some states were under disruption, the OIG acknowledged the safeguards present in the program at issue: 1. The arrangement would be provided on an interim basis for a fixed period subject to extension if the state’s malpractice insurance market did not improve. 2. The assistance was offered only to current active medical staff or physicians joining the staff who were new to the locality or in practice for less than one year. 3. The criteria for receiving assistance would not be related to the volume or value of referrals or other business generated. 4. Each physician receiving assistance would pay at least as much as he or she was previously paying for malpractice insurance. © 2003 Baird, Holm, McEachen, Pedersen, Hamann & Strasheim LLP 14 5. Participating physicians would be required to perform services for the hospital and to give up certain litigation rights. 6. Insurance assistance would be available regardless of the location at which the physicians provided services, even if the locations included other hospitals. The letter did not expressly confirm that such a program would be in compliance, noting that the OIG could not issue an advisory opinion except in accordance with the regulatory requirements. F. Hospital CEO Recently Indicted. On June 6, 2003, the CEO of Alvarado Hospital Medical Center, a subsidiary hospital of Tenet Healthcare Corporation, was indicted on eight counts of violating anti-kickback laws. The indictment pertained to physician recruitment payments made under physician relocation agreements entered into between 1995 and 1998. According to the indictment, Alvarado paid more than $10 million to physicians who agreed to relocate their practices to the area around the hospital. Claims allege a percentage of the payments passed through to the established practices in violation of the laws. This recent indictment is indicative of the need for recruited physicians to directly receive compensation rather than indirectly through any existing organizations within a hospital’s referral network. IV. Stark Law Issues. Stark prohibits billing by a hospital for any “designated health service” (including inpatient and outpatient hospital services) ordered or referred by a physician with whom the hospital has a financial relationship, unless an exception exists. A. Physician Recruitment Exception. There is an exception for physician recruitment that provides that any payments made to a practitioner to relocate his or her practice to the geographic area served by the recruiting hospital in order to be a member of the medical staff of the hospital are excepted so long as: 1. The arrangement and its terms are in writing and signed by both parties; 2. The practitioner is not required to refer patients to the hospital; 3. The amount of remuneration under the arrangement is not determined in a manner that takes into account, directly or indirectly, the volume or value of any referrals by the referring practitioner; and 4. The physician being recruited must not be precluded from establishing staff privileges at another hospital or referring business to another entity. © 2003 Baird, Holm, McEachen, Pedersen, Hamann & Strasheim LLP 15 The proposed Stark II regulations, issued January 9, 1998, only slightly modify the existing exception preventing compensation to physicians (as part of recruitment packages) from taking into account “other business generated between the parties.” Presumably this means that determination of compensation may not even consider whether there will be business generated between the parties. B. Personal Service Arrangements. The following exceptions specifically address personal service arrangements. To the extent that an arrangement does not meet the physician recruiting exception, then the personal services exception is potentially another alternative. To be protected, a personal service arrangement must meet all six of the following requirements: 1. It must be set out in writing, signed by the parties and specify the services to be provided. 2. The arrangement must cover all of the services to be provided by the physician to the entity. 3. The aggregate services contracted for must not exceed those that are reasonable and necessary for the legitimate business purposes of the arrangement. 4. The term must be at least one year. 5. The compensation to be paid over the term of the arrangement is set in advance, does not exceed fair market value and is not determined in a manner that takes into account the volume or value or referrals or any other business generated between the parties. 6. The services to be performed under the arrangement do not involve the counseling or promotion of a business arrangement or other activity that violates any state or federal law. C. Fair Market Value Exception. A new safe harbor has been established for fair market value arrangements. To be protected, a fair market value arrangement must meet all six of the following requirements: 1. It must be set out in writing, signed by the parties, and cover only identifiable items or services, all of which are specified in the agreement. 2. It specifies the timeframe for the arrangement, which can be for any period of time, and contain a termination clause, provided the parties enter into only one arrangement for the same items or services during the course of a year. An arrangement for less than one year can be renewed so long as the terms of the arrangement and the compensation do not change. 3. It specifies the compensation to be provided. The compensation must be set in advance, be consistent with fair market value, and not be © 2003 Baird, Holm, McEachen, Pedersen, Hamann & Strasheim LLP 16 determined in a manner that takes into account the volume or value or referrals or any other business generated by the referring physician. 4. The transaction is commercially reasonable (taking into account the nature and scope of the transaction) and furthers the legitimate business purposes of the purposes. 5. It meets an anti-kickback safe harbor, has been approved in an antikickback advisory opinion, or does not violate the anti-kickback statute. 6. The services to be performed under the arrangement do not involve the counseling or promotion of a business arrangement or other activity that violates any state or federal law. The final rules clarify that compensation will be considered “set in advance” if the aggregate compensation or a time-based or per unit of services-based amount is set in advance in the initial agreement between the parties in sufficient detail so that it can be objectively verified. Similarly, the regulations provide that compensation does not take into account the volume or value of referrals or the amount of business generated between the parties so long as the compensation is fair market value and does not vary during the course of the compensation agreement in any manner that takes into account the referrals of designated health services or the business generated by the referring physician including private pay health care business. DOCS/560880.1 © 2003 Baird, Holm, McEachen, Pedersen, Hamann & Strasheim LLP 17