EIGHTH INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF CLINICAL LEGAL

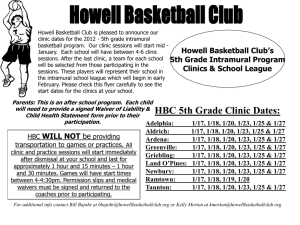

advertisement