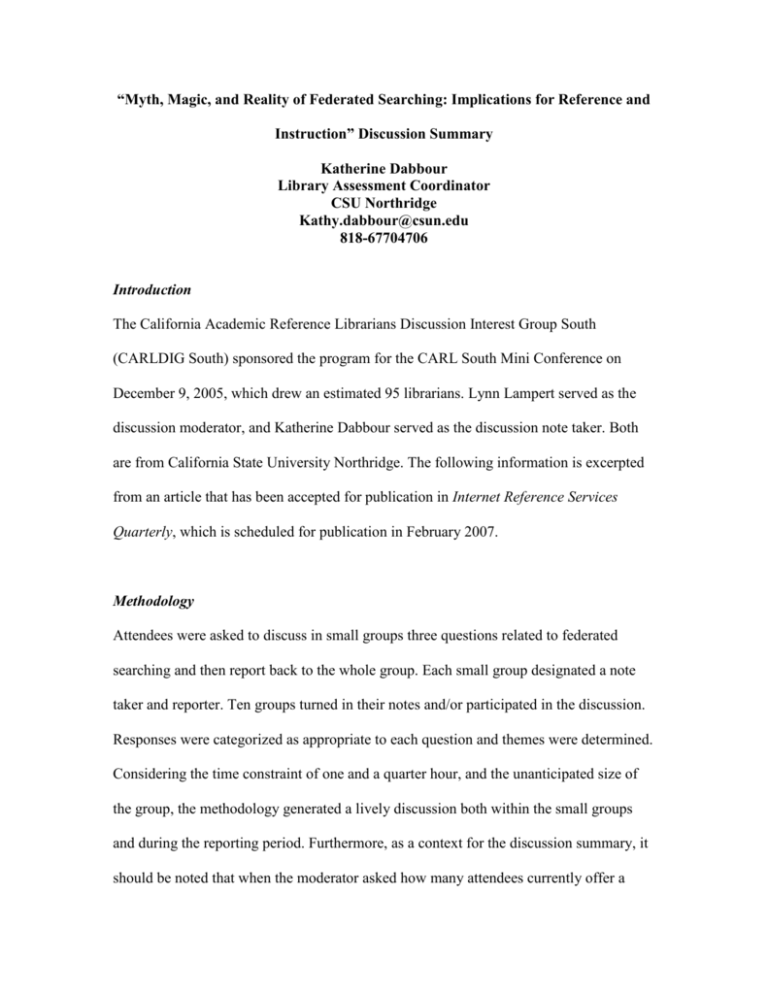

“Myth, Magic, and Reality of Federated Searching: Implications for

advertisement

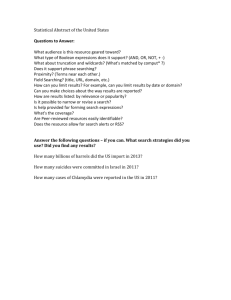

“Myth, Magic, and Reality of Federated Searching: Implications for Reference and Instruction” Discussion Summary Katherine Dabbour Library Assessment Coordinator CSU Northridge Kathy.dabbour@csun.edu 818-67704706 Introduction The California Academic Reference Librarians Discussion Interest Group South (CARLDIG South) sponsored the program for the CARL South Mini Conference on December 9, 2005, which drew an estimated 95 librarians. Lynn Lampert served as the discussion moderator, and Katherine Dabbour served as the discussion note taker. Both are from California State University Northridge. The following information is excerpted from an article that has been accepted for publication in Internet Reference Services Quarterly, which is scheduled for publication in February 2007. Methodology Attendees were asked to discuss in small groups three questions related to federated searching and then report back to the whole group. Each small group designated a note taker and reporter. Ten groups turned in their notes and/or participated in the discussion. Responses were categorized as appropriate to each question and themes were determined. Considering the time constraint of one and a quarter hour, and the unanticipated size of the group, the methodology generated a lively discussion both within the small groups and during the reporting period. Furthermore, as a context for the discussion summary, it should be noted that when the moderator asked how many attendees currently offer a federated search system in their libraries, only 10 out of the 95 said “yes.” Therefore, this discussion is most likely as speculative as the survey results previously discussed. Summary The first discussion question, which mirrored the online survey, asked, “Should federated searching be considered a starting point for teaching or providing reference assistance? Why or why not?” Three of the groups answered “yes” and most of their comments focused on the positives of a “Google-like” one-box interface as either inviting or a conceptual framework to build upon before launching into the more sophisticated search interface that an individual database vendor offers. Others commented that a federated search system could also introduce and evaluate the relevance of the resources available from a library’s database offerings by indicating which databases contained the most results for a keyword search. Others felt that a single-box interface enables the librarian to focus more on keyword choice and the search process rather than on individual databases’ search mechanics. Three of the groups answered “no,” and many of their comments focused on the lack of sophisticated searching, such as the loss of limiting to scholarly journals or access to database thesauri. Others felt that the multiplicity of formats and sheer number of results from simultaneously searching a variety of databases is confusing and would not be considered a starting point database for lower division undergraduates or community college students. Others indicated that since not all databases are metasearch compliant, e.g., Lexis-Nexis Academic and Factiva, students would also be missing these relevant resources. Four of the groups’ answers fell under the category of “it depends,” namely, that whether or not a federated search system was a starting point depended on the individual student’s and/or class’ information needs. For example, some pointed out its value for interdisciplinary research or looking up obscure topics; others echoed what was said by the groups that answered “yes” i.e., that it mainly works to help determine what library resources are available in a particular subject area and it’s value as a starting point when you don’t know where to start. Question number two asked, “What impact could federated searching have on students’ information literacy skills: Positive, negative, neutral? Why do you think that might be the case?” None of the groups said that federated searching would have an unequivocally positive or negative impact. Their responses ranged from middle-of-the-road neutral to equally positively or negatively neutral. For the mid-range neutrals, it again depended on students’ information needs: if they need it and understand it, fine, if not, it at least does not hurt information literacy skills. For the more negative neutrals, without previous instruction, they felt it would hurt students’ information literacy skills since they would not understand what the federated system was searching, or how to evaluate search results. For the positive end of the neutral spectrum, they felt federated searching could act as a “hook” or conceptual framework by building on students’ one-box search expectations already formed by their experience with Google; furthermore, at least a federated search system would encourage the use of better resources without the student knowing it. For question number 3, “Should librarians teach federated searching to a particular “type” of student, i.e., undergraduates or graduates only, grads only, etc.? Why or why not?” six of the groups indicated “yes,” citing that either graduate students, seniors taking capstone courses receiving library instruction, or classes in the majors should be taught federated searching, which was considered too specialized or difficult for basic general education classes or lower division students. Three of the groups said “no” that they would teach it to whoever needed it, citing again the idea that it depended on the question. Another group in the “no” camp said that assuming information literacy was taught on a continuum of undergraduate to graduate at a campus, then they would get it at some point.