CPR/AED Renewal for Professional Rescuers

advertisement

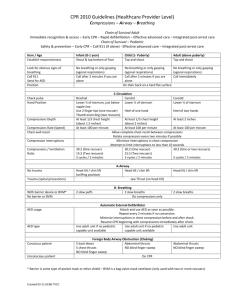

CPR/AED for the Professional Rescuer Renewal SELF STUDY EDITION (INCLUDES TEST) The objective of this course is to familiarize you with the steps involved in providing basic life support during emergencies along with rationales for these steps. This course is the first step of a two-step process for renewing your professional-level CPR certification. Step two is signing up and completing a hands-on training session. After completing this course and the hands-on training, you'll be prepared to contribute in important ways to the health and well-being of your patients, your family and the community. This course follows ILCOR and American Heart Association(R) 2005 Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care. University of Minnesota Physicians BLS programs are administered through American Safety and Health Institute (ASHI) and taught by certified instructors and certified instructor trainers. Contents Professional Rescuer Role and Responsibilities Initial Assessment Breathing Emergencies o Rescue Breathing: adult, child, infant Using a BVM Airway Obstruction o Conscious: adult, child, infant o Unconscious: adult, child, infant Acute Coronary Syndromes and CPR o One Rescuer: adult, child, infant o Two Rescuer: adult, child infant Using an AED o Adult and child Summary Authors: MWalsburg and MGross © University of Minnesota Physicians PROFESSIONAL RESCUER ROLE AND RESPONSIBILITIES What is a professional rescuer? A professional rescuer is anyone who may be called upon to provide basic life support during the course of employment. What is the difference between a professional rescuer and a lay rescuer? The distinction is largely legal. Professional rescuers have a legal duty to provide care in the event of an emergency. Professional rescuers often provide leadership in emergencies. Most emergency situations are chaotic. The leadership provided by a professional rescuer is essential to ensuring that the victim receives proper, coordinated care and that others remain safe. What if I help with an emergency outside of work? In that case, you are legally considered a lay rescuer even if you use your great skills. What happens if I take over for another rescuer? If you are acting as a professional rescuer and you arrive at a situation in which a lay rescuer has begun to provide care, you must conduct your own assessment. You can never rely on the assessment performed by a lay rescuer. However, if you arrive at a scene where another professional rescuer has started care, you can join in that care. RESPONSIBILITIES As a professional rescuer, you are expected to meet an appropriate standard of care when providing basic life support. It is your responsibility to review your skills often enough to be proficient in providing these skills when needed. It is also your responsibility to maintain current certification. LEGAL ISSUES It is important for you to understand the legal issues surrounding the provision of basic life support services. As a professional rescuer, provision of basic life support care is within your scope of practice. You have a legal duty to act and must meet the appropriate standard of care. Failure to do so may result in legal action for negligence. When acting as a professional rescuer, you are not covered by the Good Samaritan law. Duty to act means that you may be called upon to provide basic life support services within your duties on the job. Scope of practice refers to the set of skills you have acquired through your training in school as well as any ongoing training on the job. You are limited to providing only that care which is within the scope of practice for your profession and your experience level. Standard of care involves the range of correct ways to perform particular tasks and provide care. All caregivers are required to practice within the accepted standard of care. Negligence results when a caregiver fails to provide required care, fails to meet the standard of care or acts outside the scope of practice. Abandonment charges result when caregivers terminate care prematurely. Continue care until you are relieved by another professional rescuer. Even if the victim appears to recover, continue to monitor his or her condition until more advanced help arrives. Good Samaritan Law exists in every state in the country. This law protects all people acting as laypeople from ordinary liability charges when providing emergency care. In the state of Minnesota, this law requires all people to at least act as "prudent laypeople,"--that is, all people should at least call the emergency response number if they are aware of an emergency. People should also attempt to give care they know how to give. Minnesota law has additional requirements for anyone who may have caused the emergency (as in a car accident). Anyone involved in the emergency who is not hurt is required to provide whatever care they know how to provide and they must remain on the scene until an ambulance arrives. CONSENT Obtaining Consent If the victim is conscious, you must always obtain consent before touching him or her. Say, "I'm trained in first aid, can I help?" and wait for a reply. For children, request consent from a parent or guardian. If no parent or guardian is around, don't delay care--consent is implied. For unconscious, very confused or seriously injured people, consent may not be possible. In that case, consent is implied. Refusal of Care At times, even the most seriously injured or ill person may refuse care. In that situation, you have a few options: Try to reason with the person, explain who you are and what is happening. Give reassurance. This may convince the person to trust you and allow you to provide care. Even without consent, always activate the EMS system and continue to monitor the victim until the ambulance arrives. If the person loses consciousness, begin care. Battery A caregiver can be charged with battery for touching a person without their consent. While these charges are fairly rare, they can be avoided by simply obtaining consent. ROLE IN EMS CONTINUUM Professional rescuers fill an important role in the emergency medical services continuum. Professional rescuers provide critical transitional care after a lay person's initial actions and before the arrival of more advanced medical personnel. Lay Responder’s Initial Actions Professional Rescuer’s Care Prehospital Care by Advanced Personnel Hospital and Rehabilitative Care UNIVERSAL PRECAUTIONS AND PPE Employees of University of Minnesota Physicians are required to observe universal precautions. This means you must act as if all blood and bodily fluids are infected. Part of observing universal precautions is the use of appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE). At minimum, gloves must be worn when providing basic life support services. Always put on gloves before approaching the patient. You are also required to use a resuscitation mask or bagvalve-mask set up to provide ventilations to patients. Unprotected mouth-to-mouth or mouth-to-nose resuscitation is prohibited. All of our clinics have resuscitation masks and/or bag-valve-mask set ups available. Locate these items in your clinic today so you'll be able to get them quickly when you need them. The risk of infection from providing basic life support is extremely low--about one in one million. Use of PPE can reduce this risk even further. PLEASE NOTE: It is difficult to find photographs and illustrations of people wearing gloves while performing BLS procedures. Please do not take the absence of gloves in some of the pictures in this course as a sign that it is acceptable to work without gloves. Gloves are always required. AGE RANGES For purposes of basic life support, age ranges are: Infants are 0-1 year old Children are 1 year old to 12 years old (or look for signs of puberty) Adults are over 12 years old but if a child is adult-sized, treat him or her as an adult For Automated External Defibrillator (AED) use, the age range changes slightly: Children are 1 year old to 8 years old Adults are over 8 years old AEDs are not recommended for use on infants at this time INITIAL ASSESSMENT Initial assessment involves assessing the scene, assessing the victim, and activating the EMS system. ASSESSING THE SCENE When approaching an emergency situation, start by sizing up the scene: Look around for dangers that may affect your response. Are there downed power wires, flammable materials or other hazards present? If the scene is unsafe GET OUT! Look for clues as to what may have happened to the victim. There is a big difference between finding a victim slumped on the floor and finding that same victim on the floor next to a toppled ladder. In the second scenario, you might suspect head or neck injury. Get a sense of the resources needed. Is there more than one victim? Is special equipment needed? Once you have assessed the scene, don personal protective equipment before approaching the victim. APPROACH THE VICTIM Take note of the victim's appearance. Is he or she lying still or moving? Does the skin color appear normal for the victim's ethnic group? Does the victim appear to be breathing and, if so, is the breathing easy or labored? CHECK FOR RESPONSIVENESS Tap the victim on the shoulder (for an infant, tap the foot or rub the sternal area) and shout, "are you okay?" Use the victim's name if you know it. Shouting is important because as people lose consciousness, hearing is the last sense to go. Shouting may help to arouse the victim. If you are not alone, direct someone to call 911 or the emergency response number. If the victim is not fully responsive, you will need to assess the ABCs: Airway, Breathing, Circulation. THE ABCs Open the Airway and Assess for Breathing and Blockage Open the airway using the head-tilt, chin lift technique. For an adult, tilt the head far enough back that the jaw is perpendicular to the floor. For a child, tilt the head back slightly past neutral. For an infant, the head tilt is just at neutral and is sometimes referred to as "flat face." If you suspect a spinal injury, use the jaw thrust maneuver to open the airway: Brace your elbows on your legs, use your thumbs to press down on the cheeks and seal the mask, pull the jaw up into the mask with your fingers without moving the head. Once the airway is open, place your face close to the victim's nose and mouth and look, listen and feel for breathing for between 5 and 10 seconds. Breaths need to be sufficient to ventilate the person and make the chest clearly rise. Gaspy, shallow, gurgling or noisy breaths--agonal breaths--do not count. Place the resuscitation mask over the victim's nose and mouth and give two rescue breaths to assess if the airway is open. If the breaths do not go in, retilt the head, reseal the mask and try two more breaths. If the breaths go in, assess circulation. If the breaths do not go in, move to the unconscious choking procedure. Assessing Circulation Check the victim's carotid artery for a pulse. This artery is found in the notch on the side of the neck. For infants, check a brachial pulse by pressing lightly on the inside of the upper arm, against the bone. Check for a pulse for no more than 10 seconds. Blood Sweep The last step in assessing the victim is a quick check for major bleeding. Visually scan up and down the person's body and lower extremities for signs of bleeding. From start to finish the assessment should take no longer than 30 seconds. It is meant to detect life-threatening problems only. CALL FIRST VS. CALL FAST Do I call first or care first? If you are alone, you have a difficult decision. With an adult, the most common reason for collapse is a cardiac issue. It is vitally important to get an AED (automated external defibrillator) on the scene within 6 minutes. It is the combination of high quality CPR and early use of an AED that will save the person's life. Every minute of delay in using an AED decreases the chance of survival by 10%. For an adult, as soon as you have completed your assessment and find the victim has no breathing or pulse, call 911 BEFORE giving care. Return to the victim after the call and start CPR. With a child, the most common reason for collapse is a respiratory issue such as choking or asthma. Children become dangerously hypoxic quickly. Once you complete your assessment, give 2 minutes of care before stopping to call 911. Try to bring the child with you to the phone or otherwise continue care while calling 911. In short: For adults, call first. For children and infants, call fast. ASSESSING FOR STROKE Stroke (also known as cerebrovascular accident or CVA) occurs when the blood supply to part of the brain is interrupted either because of a clot or because a blood vessel ruptures. Brain cells past the point of interruption die from a lack of oxygen and nutrients. Stroke is the third leading cause of death in the United States. A host of new fibrolytic/thrombolytic drugs can greatly reduce the effects of stroke and allow many people to recover quickly and with far fewer long-term effects. However, successful treatment depends on early recognition as these new treatments must be administered within two to three hours of onset of symptoms. Symptoms of stroke are sudden and include: weakness or numbness of the face, arm, or leg, especially one-sided confusion, trouble speaking or understanding vision changes difficulty walking, loss of balance or coordination, dizziness severe headache To assess for stroke, THINK F.A.S.T.: Face: Ask the person to smile. Look for weakness or “pulling” to one side--an asymmetrical smile. Arms: Have the victim close his eyes, and hold his arms out in front of him. Look for weakness or drooping in one arm. Speech: Ask the victim to repeat a common phrase such as “I scream, you scream, we all scream for ice cream.” Look for difficulty with annunciation (indicating possible paralysis of the vocal muscles and throat) or difficulty using common words (indicating issues in the speech formation area of the brain). Time: Note the time of onset of symptoms. The new medications must be administered quickly. The American Heart Association stroke protocol calls for patients to be under a CT scanner within 45 minutes of onset of symptoms. If treated timely, some strokes can be reversed and the long-term effects significantly reduced. MOVING THE VICTIM In general, it is best not to move the victim. Only move the victim to remove him or her from an unsafe area or to enable you to provide care. If you must move the victim, use the Clothes Drag method, as this allows you to secure the head and neck and minimize spinal movement: Stand behind the victim Gather the victim’s collar and clothing in your hands on the sides of the neck Secure the victim’s head and neck with your forearms Pull the victim to safety BREATHING EMERGENCIES A victim who has stopped breathing is in respiratory arrest or failure. This can develop from respiratory distress (difficulty breathing) or suddenly as a result of an obstructed airway, heart attack, or other cause. A victim who has a pulse but is not breathing--or not breathing normally--needs assistance with ventilation. This is called rescue breathing. USING A MASK EFFECTIVELY Remember that it is UMPhysicians policy that you always use either a resuscitation mask or a bagvalve-mask set up to provide ventilations. Proper use of a Resuscitation Mask Place the base (wide part) of the mask in the curve between the chin and the lower lip. Rest your hand nearest the head on the victim's forehead and form a C with your thumb and index finger to seal the top of the mask. Place the thumb of your other hand on the base of the mask and use your fingers to grasp the jaw and pull it up into the mask. This generally gives a very good seal. If you are working at the top of the head (as in two-rescuer CPR), form the thumbs and fingers of both hands into Cs on each side of the mask and use the other three fingers of both hands to pull the jaw up into the mask. For infants use a pediatric mask but if only an adult mask is available, reverse the direction of the mask, placing the "nose point" on the infant's chin. RESCUE BREATHING Rescue breathing is the process of breathing air into a victim to give him or her the oxygen needed to survive. Inhale a normal breath Deliver a breath to the victim via mask Each breath should be expelled over 1 second Each breath should cause gentle chest rise Adult rate is 1 breath every 5 seconds. As you work, count "1-one thousand, 2-one thousand, 3-one thousand" then breathe in on four and breathe out on five. Child/infant rate is 1 breath every 3 seconds. As you work, count "1-one thousand" then breathe in on two and breathe out on three. Stop and check for a pulse every two minutes Rescue breathing should continue until: The victim can breath on their own Another trained rescuer takes over for you You are too exhausted to continue The scene becomes unsafe The victim has no pulse--then start CPR immediately or apply an AED A Word about Speed and Volume: In an emergency, rescuers tend to breath too deeply and deliver breaths forcefully over a brief period. This blast of air meets resistance in the trachea and ends up going down the esophagus instead of into the lungs. This results in abdominal distention, which can cause two problems. As the stomach fills with air it presses against the diaphragm, increasing intrathoracic pressure. This added pressure makes it even harder to inflate the lungs and impedes venous return to the heart, reducing the quality of CPR. The air also displaces stomach contents, causing the victim to vomit. If this happens, roll the victim to one side, clear the mouth with your (gloved) finger, shake out the mask, and resume rescue breathing. DO NOT allow the victim to aspirate! A Word about Dentures: If the victim is wearing dentures, do not remove them unless they become dislodged. Dentures help to maintain the shape of the mouth and increase your ability to make a tight seal with the mask. USING A BVM BVM stands for bag-valve-mask set up. This device is used to ventilate victims in respiratory distress or respiratory arrest. These devices consist of a ventilation bag, a one-way valve and a mask to seal over the victim's mouth and nose. BVMs come in adult, child and infant sizes. As with masks, an adult BVM can be used with a child or infant. Do not squeeze the bag as much. Avoid overventilation by paying close attention to the level of chest rise. The purpose of using a BVM is to increase the level of oxygen delivered to the patient. Breath delivered by a rescuer through a face mask contains 16% oxygen. Room air delivered through a BVM contains 21% oxygen. THE BVM AND OXYGEN Many BVMs include tubing and a reservoir for supplemental oxygen. This greatly increases the level of oxygen delivered to the patient. Using a BVM with oxygen at 15 liters per minute can deliver nearly 100% oxygen, which benefits a patient who has been hypoxic. Do not attach oxygen if you have not been trained to do so Remove the BVM (keep the mask) and move the O2 tank away before shocking with an AED. AED shocks have caused fires in the presence of oxygen. USING A BVM FOR TWO RESCUERS It can be tricky for one rescuer to use a BVM. It is preferred that two rescuers use a BVM. Rescuer one completes the assessment and determines the need for ventilations while rescuer two assembles the BVM (including oxygen, if used). Rescuer one seals the mask on the victim's face and opens the airway. Rescuer two counts and squeezes the bag to administer the ventilations. Ventilations are delivered over one second as rescuer two watches for the chest to gently rise. For adults: Deliver one ventilation every five seconds. Rescuer two counts "1-one thousand, 2-one thousand, 3-one thousand, 4-one thousand" and delivers the ventilation on the fifth count. For children and infants: Deliver one ventilation every three seconds. Rescuer two counts "1-one thousand, 2-one thousand" and delivers the ventilation on the third count. As with rescue breathing, stop every two minutes to check for a pulse. USING A BVM FOR ONE RESCUER While awkward, it is possible for one rescuer to use a BVM. Seal the mask with one hand using the C-E method: place the thumb and forefinger in a C shape around the side rim of the mask. Use the other three fingers in an E shape to grasp the jaw and pull it up into the mask. Squeeze the bag with the other hand. You may have to squeeze a bit more, as more air tends to leak around the mask with one rescuer. Determine appropriate volume by watching for gentle chest rise. Small Study Illustrates Paramedic Bag-Valve-Mask Proficiency on Child/Infant Manikins By J.M. Hendry http://www.merginet.com/index.cfm?pg=pediatric&fn=bvmprof July 2005, MERGINET—A two-person bag-valve-mask ventilation technique—one person using two hands to obtain an airtight seal between the mask and the manikin while the other compresses the bag—was superior to one-person bagvalve-mask ventilation on infant and child manikins, according to a small study conducted in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. However, among the healthcare professionals participating in the study, “the paramedic provider group generated higher median tidal volumes per weight than all other groups for the infant- and child-manikin models,” wrote Lara Davidovic, MD, MPH, of the Division of Pediatric Emergency Medicine and colleagues at Children's Hospital of Pittsburgh. Paramedics were the only providers able to generate the target tidal volume per weight of 10 mL/kg while using the twoperson technique in the infant manikin and both techniques in the child manikin. The researchers enlisted 70 healthcare providers—10 from each group of one-, two- and three-year postgraduate pediatric residents, two-year postgraduate emergency medicine residents, pediatric emergency nurses, paramedics and ambulance transport personnel—to perform the two bag-valve-mask ventilation techniques on an infant and a child manikin set up to record tidal volume and peak pressure every 15 seconds during three minutes of ventilation. Oral airways were not used. The averaged data from each group reveals greater mean tidal volumes per weight, mean pressures and mean highest peak pressures overall during two-person bag-valve-mask ventilation in both infant and child manikins. The paramedic group achieved median tidal volumes of 8.4 mL/kg and 11.7 mL/kg, respectively, during one- and two-person infant ventilation, and 11.2 mL/kg and 12.7 mL/kg, respectively, during one- and two-person child ventilation. By comparison, none of the other groups achieved the target 10 mL/kg using either technique on either manikin. “The importance of mastering the technique of bag-valve-mask ventilation cannot be overestimated,” the authors noted since “An emphasis on providing sustained bag-valve-mask ventilation rather than endotracheal intubation in the out-ofhospital setting is increasing.” In this study, both the paramedics and the ambulance transport personnel reported a median of 250 lifetime experiences with bag-valve-mask ventilation. “One would expect the provider groups with the most experience to generate the best outcome,” the authors wrote. “However, this did not hold true for the transport group,” which had median tidal volumes of 4.1 mL/kg, 7.3 mL/kg, 6.3 mL/kg, and 9.1 mL/kg in one- and two-person infant and one- and two-person child ventilation, respectively. While data from this study is limited due to the small sample size, the investigators reasoned “there is a paucity of studies demonstrating the effectiveness for practicing bag-valve-mask on manikins.” This study revealed “that many current providers did not generate recommended tidal volumes in a manikin model,” and that two-person ventilation with a bagvalve-mask in infants and children is generally preferable. Reference Davidovic L. LaCovey D. Pitetti RD. “Comparison of 1- Versus 2-Person Bag-Valve-Mask Techniques for Manikin Ventilation of Infants and Children.” Annals of Emergency Medicine, July 2005, Volume 46, Number 1. AIRWAY OBSTRUCTION Foreign body airway obstruction is the most common cause of respiratory emergencies. A person with a blocked airway can quickly lose consciousness and die. Children are especially at risk because their airways are much smaller than adults and because young children tend to put small objects into their mouths. Airways can be partially or fully obstructed. Professional rescuers must be able to recognize signs of airway blockage. The universal choking sign is two hands around the throat. Fast action is the key to survival. Brain death can start as early as four minutes after total obstruction and is complete in ten minutes or less. Calling 911 Many people are embarrassed to call 911 "just for" choking. Calling 911 is vitally important because even if a person is still conscious, you can't predict that you will be successful in clearing their airway before they lose consciousness. Paramedics have devices that can help clear stubborn foreign bodies from airways. It is important to get them on their way. Prevention Matters For children, hard foods such as candy and nuts, are the most common agents of choking. Hot dog rounds have been cited in a number of choking episodes. Coins are involved in 18% of choking incidents. Latex balloons can also be aspirated. Cut round foods like carrots and hotdogs long-ways first before slicing. Keep coins, latex balloons and small toys/toy parts away from children. For adults large pieces of food, especially meet, often causes choking. Alcohol consumption increases the risk. Adults need to be reminded to cut meats into smaller pieces, to chew food carefully, and not to talk or laugh while eating. CONSCIOUS CHOKING: ADULT AND CHILD Adult: When caring for a conscious choking adult, remember to identify yourself as someone who can help. Ask if he or she is choking, and obtain consent. If the victim is coughing forcefully, some air is still getting into the lungs. Encourage the victim to keep coughing. If the victim is no longer able to cough or breathe, start the conscious choking protocol: Place an arm under the victim's arm and across the chest; stand behind and to the side Give 5 back blows between the shoulder blades. Each blow should be a distinct attempt to dislodge the foreign object If the back blows don't clear the object, make a fist and wrap your arms around the person, placing the thumb side of your fist against the abdomen just above the navel. Grasp your fist with your other hand and deliver 5 abdominal thrusts. Each thrust should be in a “J” motion of up and back and should be a clear attempt to dislodge the foreign body. If the victim is obviously pregnant or is too big for you to reach around them, use chest thrusts: grasp your hands high on the center of the chest and give 5 thrusts straight back toward you. Rotate between 5 back blows and 5 abdominal thrusts (or chest thrusts) until the object is dislodged and the victim can breath on his or her own, or until the person becomes unconscious. If the victim becomes unconscious, step backward to lower him or her to the floor and proceed to the unconscious choking protocol. Abdominal Thrust--Adult Chest Thrust--Adult Child: Care for a choking child the same way you care for a choking adult except you will not deliver the back blows or abdominal thrusts as forcefully on a child. If a parent or guardian is not around, you have implied consent to help the child. You may need to get on your knees in order to adapt to their size. CONSCIOUS CHOKING: INFANT For an infant you will use a combination of 5 back blows and 5 chest compressions. While seated with extended leg, cradle the infant's face and neck on your hand and bring the infant's body over that arm onto your extended leg. Hold firmly as the infant will likely be flailing about. Give five firm back blows between the shoulder blades. Each back blow should be a separate attempt to dislodge the object. Using the hand that gave the back blows, grasp the back of the infant's head and neck. Extend the other leg and flip the infant over onto your arm and extended leg. Give five chest thrusts: Place two fingers just below the nipple line and compress 1/2 to 1 inch. Each compression should be a separate attempt to dislodge the object. Continue alternating back blows and chest thrusts until the object clears and the infant is able to cry on his or her own or until the infant becomes unconscious. If the infant loses consciousness, move into the unconscious choking protocol. UNCONSCIOUS CHOKING: ADULT AND CHILD The treatment for unconscious choking is very similar to CPR. Adult: If during assessment breaths do not go in, reopen the airway and try two breaths again. If they still do not go in: Kneel next to the victim. Position your two hands on top of one another on the center of the sternum. Lace your fingers together and lift them off the chest. Only the heel of your hand should touch the chest. With shoulders over hands and elbows straight, deliver five chest thrusts at a depth of 1.5 to 2 inches. Allow the chest to recoil fully after each thrust so that each thrust is a separate attempt to remove the object. Open the victim's mouth by grasping the jaw and tongue. Look in the mouth for a foreign object. If you see the object, remove it with your finger. Replace the mask, open the airway and try two more breaths. o If the breaths do not go in, continue cycles of five chest compressions, foreign object check, two rescue breaths o If the breaths go in, you have cleared the airway. Check for breathing and a pulse and proceed based on what you find. Child: Use the same pattern as above (5 chest thrusts, foreign body check, two breaths) but compress the chest only 1 to 1.5 inches. You can also give chest thrusts using one hand. The other hand remains on the forehead, maintaining the open airway. UNCONSCIOUS CHOKING: INFANT If during assessment breaths do not go in, reopen the airway and try two breaths again. Often with infants we tilt the head back too far so try tilting a bit less. If breaths still do not go in: Place two fingers on the center of the chest below the nipple line as you did during conscious choking. Deliver five chest thrusts at a depth of 1/2 to 1 inch. Allow the chest to recoil fully after each thrust so that each thrust is a separate attempt to remove the object. Open the victim's mouth by grasping the jaw and tongue. Look in the mouth for a foreign object. If you see the object, remove it with your little finger. Replace the mask, open the airway and try two more breaths. o If the breaths do not go in, continue cycles of five chest compressions, foreign object check, two rescue breaths o If the breaths go in, you have cleared the airway. Check the pulse and proceed to care for what you find. ACUTE CORONARY SYNDROMES AND CPR Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death for both men and women in the United States, accounting for about 40% of all deaths. Over 927,000 people die in the U.S. of cardiovascular disease each year--one person every 34 seconds. The term "acute coronary syndromes" describes a number of conditions ranging from unstable angina to myocardial infarction (MI--or heart attack). ACS occurs when coronary artery occlusion prevents the heart muscle from receiving adequate flow of oxygenated blood. The heart muscle becomes injured and will eventually die, causing disability or death. ACS is the cause of sudden cardiac arrest in most patients. In many cases, the coronary artery doesn't just become plugged. The plaque lining an artery ruptures, spilling out loose fat. Thrombocytes (clotting cells) stick to the walls of the ruptured plaque and the fat droplets and create clots in the vessel, which float down to and occlude smaller coronary artery branches. CARDIAC EMERGENCIES Cardiac Chain of Survival There are 4 links in the cardiac chain of survival: Early recognition of the emergency and early access to EMS Early CPR Early defibrillation Early advanced medical care Most deaths following myocardial infarction occur before the patient reaches the hospital. About 50% of these deaths occur due to failure to treat ventricular fibrillation in a timely manner. The most important factors for survival after myocardial infarction are timely defibrillation followed immediately by high-quality CPR. Contrary to popular belief, CPR rarely restarts the heart. The goal of CPR is to move oxygen-rich blood to the tissues, especially the brain, until a normal heart rhythm can be restored. Advanced medical care is needed to address the underlying cause of the myocardial infarction and to restore a normal rhythm. Recognizing MI Classic symptoms of myocardial infarction include: Chest pain, pressure or discomfort behind the sternum that may spread to the shoulders, neck, jaw, back, or epigastric area Shortness of breath Weakness, nausea, dizziness Heavy sweating Pale, ashen skin--especially around the face Sense of impending doom Uncertainty, embarassment and denial Women, diabetics and the elderly often do not experience chest pain but may have some of the other symptoms, particularly back and epigastric pain. They may also have pain in unusual places like elbow pain. Women tend to downplay their symptoms, delaying care. Care for Myocardial Infarction The most important step to take when you suspect MI is to call 911. Do not let the victim dissuade you from calling. While waiting for the ambulance to arrive: Place the victim in a comfortable position and loosen clothing Assist with the administration of the victim's prescribed nitroglycerin (unless they've used Viagra or Cialis in the last 48 hours) Ask the patient: "Have you ever been told by a doctor to NEVER take aspirin?" If the answer is no, have the patient chew one adult aspirin or four baby aspirin. Administer supplemental oxygen if trained to do so Reassure the patient Monitor vital signs and be prepared to administer an AED and CPR if the patient becomes unconscious ONE RESCUER CPR: ADULT If an unconscious adult is not moving or breathing and has no pulse, begin CPR. Kneel next to the victim and position yourself as you did for unconscious choking o hands laced and heel of one hand on the center of the chest o shoulders over hands o elbows locked Start cycles of 30 chest compressions and 2 rescue breaths, at the rate of 100 compressions a minute. Compress fast and hard! Compress the chest to a depth of 1.5 to 2 inches Let the chest recoil to its normal position after each compression by taking your weight off the chest (but leave your hands in place) DO NOT STOP CPR FOR PULSE CHECKS Continue CPR until o an AED is ready to use o another rescuer relieves you o the scene becomes unsafe o you are too exhausted to continue o you become aware of a sign of life--the patient moves, breathes or speaks Why are we now giving 30 compressions? When it comes to perfusing the tissues with oxygenrich blood, the name of the game is blood pressure. What we now know is that it takes 11 or more compressions before the blood pressure starts to reach levels adequate to push blood into the fine vessels. Thirty compressions are needed to get adequate blood supply to all of the tissues. Why are we saying push fast and push hard? Chest compressions raise intrathoracic pressure and mechanically squeeze the heart to move blood. Pushing fast helps to maintain the intrathoracic pressure level. Pushing hard ensures that the left ventricle, which is mostly posterior to the right ventricle, gets adequate mechanical compression to push blood out to the body. ONE RESCUER CPR: CHILD Child CPR is very similar to that of an adult; however the depth of your compressions should be 1 to 1.5 inches. The cycle for a child is 30 compressions and two breaths, at a rate of 100 compressions per minute. For a child, you can choose the one-handed method. Compress the chest with one hand, while holding the forehead of the victim with your other hand to maintain an open airway. ONE RESCUER CPR: INFANT Infant CPR is very similar to adult and child CPR except the chest compressions are less deep and you use a different chest compression technique. The cycle for infant CPR is 30 compressions and two breaths, at a rate of 100 compressions per minute. Compress the chest 1/2 to 1 inch and allow it to recoil after each compression Compress the chest using two fingers just below the nipple line. This is the same placement you used for chest thrusts in unconscious choking. TWO RESCUER CPR: ADULT When an additional rescuer is available, provide two-rescuer CPR. In adult two-rescuer CPR: Rescuer 1 performs chest compressions Rescuer 2 provides rescue breaths A cycle consists of 30 compressions followed by 2 breaths, at a rate of 100 compressions per minute Compression chest depth remains 1.5 to 2 inches The rescuer giving chest compressions counts out loud. Counting out loud is an essential form of communication. Rescuers should change positions every two minutes, as alternating reduces fatigue and improves the quality of CPR. The rescuer performing chest compressions calls for the change by replacing the word "change" on the last count, as in "28-one thousand, 29-one thousand, CHANGE." Once the change has been called, rescuer 2 finishes the cycle with two breaths then moves quickly to the patient's side and begins chest compressions while rescuer 1 moves to the head of the patient, prepares a resuscitation mask and waits to give breaths. Changing positions should take less than 5 seconds. When CPR is in progress by one rescuer and a second rescuer arrives on the scene, the second rescuer should make sure advanced medical personnel have been summoned. If they have not been summoned, the second rescuer should do this before getting the AED or assisting with care. TWO RESCUER CPR: CHILD Two-rescuer CPR for a child is similar to adult CPR except that the count changes to 15 compressions followed by 2 breaths at a rate of 100 compressions per minute. Chest depth remains at 1 to 1.5 inches. After two minutes of care, rescuer 1 calls for the change on the 15th compression. Rescuer 2 completes the cycle with two breaths then moves quickly to the patient's side and starts compressing the chest while rescuer 1 moves to the patient's head, readies a resuscitation mask and waits to give breaths. TWO RESCUER CPR: INFANT Two-rescuer CPR for an infant is similar to two-rescuer CPR for a child. The cycle for infant tworescuer CPR is 15 compressions followed by 2 breaths, at a rate of 100 compressions per minute. Chest depth for compressions is still 1/2 to 1 inch. However the rescuer compressing the chest uses the two-thumbs-encircling-hands technique. In this technique, the rescuer wraps her hands around the infant with the two thumbs side by side on the infant's chest just below the nipple line. During compressions the rescuer presses and releases the chest with the thumbs, taking care not to squeeze the sides of the chest. As with adult and child two-rescuer CPR, rescuers quickly change position every two minutes. CPR RECAP Summary of CPR Techniques Adult Hand position: Two hands on center of 1 rescuer chest Child Two hands or one hand on center of chest Infant Two fingers on center of chest just below nipple line Hand position: 2 rescuer Same Same Compression depth 1.5 to 2 inches 1 to 1.5 inches 0.5 to 1 inch Breathe Over 1 second with enough volume to cause gentle chest rise Over 1 second with enough volume to cause gentle chest rise Over 1 second with enough volume to cause gentle chest rise Cycle: 1 rescuer 30 compressions 2 breaths 30 compressions 2 breaths 30 compressions 2 breaths Cycle: 2 rescuer 30 compressions 2 breaths 15 compressions 2 breaths 15 compressions 2 breaths Rate 100 compressions per minute 100 compressions per minute 100 compressions per minute Two-thumbs-encirclinghands USING AN AED Use of an AED can significantly increase the chance of survival after myocardial infarction. However, to be effective the rescuer must assess the victim quickly and be prepared to use an AED in all cases of cardiac arrest. Each minute of delay in using the AED decreases the chance of survival by 10%. In this section you will learn how an AED works and how to use it effectively with adults and children THE HEART’S ELECTRICAL SYSTEM The heart has a special nerve conduction system that provides electrical pathways to move contractions through the heart. In the heart, a contraction starts at the sinoatrial (SA) node, located in the right upper atrial wall. The nerve impulse is conducted through the atria and down to the atrioventricular (AV) node located in the posterior septal wall of the right atrium, behind the tricuspid valve. The impulse then proceeds toward the ventricular septum along the Bundle of His, then down the septum via the right and left bundle branches. From there, the impulse moves throughout the ventricular myocardium by way of the Purkinje fibers. HOW AN AED WORKS During a cardiac emergency, clots in the coronary arteries (the arteries that feed the heart muscle) cause the heart muscle to receive inadequate oxygen. As the muscle becomes starved for oxygen, it starts to beat faster and faster to compensate. This rapid rhythm (generally greater than 150 beats per minute) is called ventricular tachycardia or VTac. Because the heart is beating so rapidly, the chambers don't have time to refill so the beats are not very productive. Therefore, even though the person appears on an EKG to have a regular heart rhythm, their heart isn't moving blood adequately. A person with VTac may have only a weak pulse or no pulse. Eventually, the heart rhythm will devolve into ventricular fibrillation, also known as VFib. In ventricular fibrillation, the heart muscles contract individually but don't work together to move the blood. If the heart could be seen through the chest, it would look like a twitching bag of worms. A person with VFib has no discernable pulse. An Automated External Defibrillator (AED) works by detecting the heart rhythm and applying the appropriate treatment. If the AED detects VTac or VFib, it will deliver a shock to stop the heart so that it can restart with a more normal rhythm. If the AED detects either a normal rhythm or asystole (a completely stopped heart), the device will instruct the user to continue CPR and will time the user for two minutes. After two minutes, the device will reanalyze the heart rhythm and deliver another shock if needed. USING THE AED: ADULT AND CHILD The Automated External Defibrillator (AED) can be used on adults, and children. For purposes of using an AED, a child is defined as 1-8 years of age or up to 55 pounds. If an AED is immediately available, use it as soon as you determine that the victim has no pulse. It is imperative to get an AED on a victim as soon as possible. To Use an AED 1) Turn on the unit and follow the instructions. 2) Pull or cut open the victim's shirt. If the victim is a woman, cut open the bra or pull it down to the waist. 3) Dry the victim's chest with their clothing or other cloth. 4) Apply the pads Place one pad on the victim’s upper right chest Place the other pad on the victim’s left lower side--deep on the left side (centered over the midaxillary line) If the patient is small, make sure the pads do not touch. If necessary, move the upper right pad to the center of the chest and the lower left pad to the center of the back, between the shoulder blades. If the victim is a child, use pediatric pads. Otherwise check to see if the unit has a pediatric key or pediatric setting that allows you to use adult pads with children. Adult Placement Child Placement 5) Once you have attached the pads, plug in the connector which will start the AED analyzing the rhythm. When you hear, "analyzing rhythm, stand clear” loudly tell everyone to back away at least 18 inches. 6) If the AED detects VTac or VFib, the device will state, "charging" and will instruct you to "press the shock button." Before you press the shock button, loudly state, "shocking, stand clear" and look to ensure that everyone--including you--is at least 18 inches away from the patient. Press the flashing button to deliver the shock. 7) The AED will announce "shock delivered" and tell you to begin five cycles of CPR. Immediately start compressing the chest to start the CPR cycle. Leave the pads in place. 8) The device will time you for two minutes. After two minutes of CPR, the AED will announce, “analyzing rhythm” and will start the sequence over again. AED CONSIDERATIONS AEDs use electricity to stop the heart. Therefore, there are a few important considerations to keep in mind as you use the AED: Make sure the victim's chest is dry. If the victim is in water, move the victim to a dry area and strip off wet clothing. Do not use alcohol to wipe the victim's chest as this could cause a fire. Pads are very sticky and will generally work even on very hairy areas. If the victim has a hairy chest, part the hairs and stick the pads down to the skin. If this doesn't work and you have a second set of pads, stick the first pads down and remove them quickly to rip some of the hair from the chest. Do not use pediatric pads on an adult, as they will not deliver enough electricity to defibrillate. If the victim is wearing a medication patch on the chest, remove the patch with a gloved hand. Never place the pad over a medication patch. Most implantable chest devices are on the upper left. However, if the patient has a device implanted in the area where a pad would be placed, simply move the pad over to clear the device. Never place a pad on top of an internal pacemaker or other implanted device. NEVER use a cell phone within 6 feet of an AED. Cell phones interfere with the functioning of an AED. Once you've activated the emergency response system, toss your cell phone well away from the victim. REMOVE oxygen from the victim before pressing the shock button. There have been many reports of fires when oxygen tubing was present during a shock from a defibrillator. USING AN AED WITH CPR IN PROGRESS If another rescuer arrives on the scene with an AED after you have started CPR, continue your cycle while the other rescuer prepares the AED, wipes off the chest and applies the pads. As soon as you hear "analyzing rhythm," step back and wait for approximately 5 seconds. If a shock is advised, resume chest compressions even while the device is charging. When the device is ready to shock, step back while the shock is delivered then quickly resume chest compressions. The combination of rapid use of an AED followed quickly with high quality CPR is the most effective way to ensure survival for the victim of a cardiac emergency. SUMMARY You have now completed the knowledge portion of the basic life support course and are ready to complete the attached test. Bring the test with you to the hands on portion of your training. Be sure to schedule yourself for a hands-on class in NetLearning or through the training department. UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA PHYSICIANS CPR/AED for the Professional Rescuer Self Study Test Circle the letter for the best answer for each question. Bring the completed test with you to the hands-on portion of your training. 1) If a child's chest does not clearly rise with the first two rescue breaths, you should A. give 15 compressions and two breaths B. reposition the airway and try the breaths again C. perform five abdominal thrusts and look in the mouth for a foreign object D. check the pulse and start CPR if the pulse is under 60 beats per minute 2) The proper hand position for chest compressions in a 7-year-old child is A. One hand on the upper third of the breast bone B. Two hands on lowest portion of the breast bone C. One or two hands on the center of the chest between the nipples D. Two fingers on the breast bone just below the nipple line 3) You have opened the airway of an unresponsive 47-year-old male. To assess for adequate breathing, you should A. feel for a carotid pulse. B. look at the chest and listen and feel for air movement. C. listen to the chest for equal lung sounds. D. give two rescue breaths then look in the mouth for any obstructions. 4) The proper hand position for one-rescuer chest compressions on a 3-month-old infant is A. 1 or 2 hands on the center of the chest at the nipple line B. 2 fingertips just above the nipple line C. 2 fingertips just below the nipple line D. two thumbs encircling hands 5) You are attending to a child who has just been struck by an automobile. To open the airway, use the A. head tilt-chin lift method B. bag-valve-mask device C. jaw thrust maneuver D. HAINES recovery position 6) The proper depth of chest compressions in a child is A. 1/2 to 1 inch B. 1 1/2 to 2 inches C. 1 to 1 1/2 inches D. 2 to 2 1/2 inches 7) Two rescuers are attending to a 9-year-old child who collapsed suddenly. An AED is available. They should A. Attach the AED only if it has the child pads/system B. Attach the AED and follow the voice prompts C. Start CPR at a ratio of 15 compressions to 2 breaths D. Start CPR at a ratio of 30 compressions to 2 breaths 8) If you suspect a person may be having a stroke, think FAST by asking the person to perform these three tests: A. Inhale deeply, speak and drink water. B. Cough, stand and write a simple sentence. C. Smile, raise both arms and speak a simple sentence. D. Walk a straight line, touch the nose, speak a simple sentence. 9) It is important to have everyone stand clear when delivering a shock from an AED because A. the AED will not deliver the shock if people are touching the victim B. the AED will not analyze the victim's rhythm C. bystanders could be injured by the shock D. the pads could become loose 10) The AED indicates that no shock is advised after analyzing the rhythm. You should A. immediately reanalyze the rhythm B. recheck pad placement on the victim's chest C. reset the AED by turning it off and back on D. continue CPR until the AED reanalyzes 11) During the initial assessment, you have checked the scene, checked for responsiveness, opened the airway and checked for breathing and a pulse. The last step in the initial assessment is to A. check for bleeding B. check for signs of life C. place the victim in the recovery position D. open and prepare the AED 12) The two rhythms that are shockable by the AED are A. ventricular fibrillation and asystole B. ventricular tachycardia and asystole C. ventricular tachycardia and ventricular fibrillation D. ventricular systole and ventricular fibrillation 13) On an adult, AED pads are placed A. on the lower left side of the chest and the lower right side of the chest B. on the upper right side of the chest and the lower left side of the chest C. on the center of the chest and on the lower right side D. over medication patches and implanted devices 14) As a single rescuer giving CPR to an adult, you should A. compress the chest about 1/2 inch B. compress the chest straight down for 1 inch C. give cycles of 15 compressions and 2 breaths D. give cycles of 30 compressions and 2 breaths 15) Chest compressions are performed at a rate of A. about 60 compressions per minute B. less than 90 compressions per minute C. about 100 compressions per minute D. at least 130 compressions per minute 16) Where do you position your hands to give abdominal thrusts for a conscious child who is choking? A. We don't use abdominal thrusts on conscious children who are choking B. In the middle of the abdomen, just above the navel C. In the middle of the abdomen, just below the navel D. Higher on the center of the chest 17) The advantage of using a BVM to ventilate a patient is A. rescuers get less tired B. higher volume ventilations C. it's easier to seal the BVM than a regular mask D. the patient gets more oxygen 18) If a child is small, the correct positioning for AED pads is A. right upper chest, left lower chest B. center of chest, center of back between shoulder blades C. parallel on the center of the chest D. right upper chest, center of back between shoulder blades 19) You are by yourself when you come upon a young child who is not breathing and has no pulse. As soon as you finish the initial assessment, you should A. provide 2 minutes of care before calling for advanced medical personnel B. immediately call advanced medical personnel C. attempt two rescue breaths D. place the child in a recovery position 20) For University of Minnesota Physicians employees performing basic life support, resuscitation masks (or BVM setups) are A. available B. mandatory C. optional D. wasteful 21) You and another rescuer are attending to a 17-year-old found unresponsive with inadequate, gasping breaths. After giving two rescue breaths and checking for a pulse, you are not certain if the pulse is present or not. You should A. Start CPR in cycles of 15 compressions and two breaths B. Start CPR in cycles of 30 compressions and two breaths C. Attach the AED and follow the voice prompts D. Continue to check for a pulse 22) You are a member of an emergency response team. You arrive on the scene and find a coworker, who is not a professional rescuer, performing CPR. What do you do? A. Begin questioning bystanders about what they witnessed B. Inform the coworker that you will take over chest compressions C. Offer to get an AED since the coworker seems to know what to do D. Reassess the victim and provide appropriate care 23) You and another professional rescuer find an unconscious adult on the floor. You send the other rescuer to summon advanced medical personnel and get an AED. As you perform the initial assessment you find the victim is not moving or breathing and has no pulse. You should A. reposition the airway and give two more breaths B. give 5 back blows and 5 chest thrusts C. begin CPR until the AED arrives D. wait until the AED arrives 24) Immediate care for a person experiencing symptoms of a heart attack includes A. drinking enough water to remain hydrated B. administering an adult aspirin if it is not contraindicated C. having the person take a nap D. driving the person to the hospital 25) When two rescuers are performing CPR on a child, the rescuer giving chest compressions calls for a change on the A. 1st breath B. 2nd breath C. 15th compression D. 30th compression 26) If you must move a victim, the one method that allows you to limit head and neck motion is the A. blanket drag B. foot drag C. clothes drag D. two-person seat carry 27) When giving rescue breaths, giving too much volume or delivering the breaths too quickly can lead to A. bloody nose and headache B. chest recoil and intrathoracic pressure C. hyperventilation and respiratory suppression D. vomiting and aspiration 28) A child has become unconscious after choking. To treat this child, you A. give 5 abdominal thrusts followed by finger sweep and two rescue breaths B. give 5 back blows and 5 abdominal thrusts followed by a finger sweep C. give 5 chest compressions followed by foreign body check and two breaths D. place the child in the HAINES recovery position 29) You assess an unconscious infant and find a pulse but no breathing. You should A. begin back blows and chest thrusts to clear the airway B. deliver one rescue breath every five seconds C. deliver one rescue breath every three seconds D. begin CPR on the infant at a rate of 100 compressions per minute 30) While crawling around on the floor, an 11-month-old suddenly starts gagging and coughing forcefully. You should A. Watch closely and be ready to take action if the symptoms worsen B. Give abdominal thrusts rapidly until the object is expelled C. Give five back blows and five chest thrusts until the object is expelled D. Give forceful rescue breaths until the chest clearly rises