Social Policy Analysis Models: Karger & Stoesz, Gilbert & Terrell

advertisement

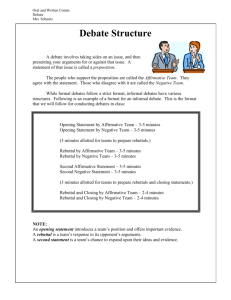

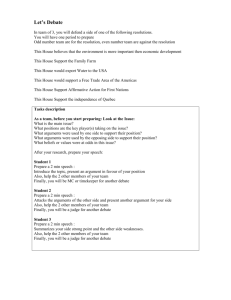

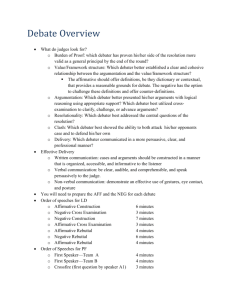

SW 610 – Week 1 Notes Introduction This course in social policy assumes that you are already familiar with policy analysis. Two models you should have been exposed to are the Karger and Stoez model and the Gilbert and Terrell Model. The following summaries of those models are based on notes prepared by Professor McCleary. Karger & Stoesz Model The framework has four sections: – – – – Historical background of the policy Description of the problem that necessitated the policy Description of the policy The policy analysis o (General analysis) o Political Feasibility o Economic Feasibility o Administrative Feasibility o Final Key Questions Various questions should be answered in each section. The questions are for illustration and clarification. Many of the questions overlap each other, and some of the questions would not fit particular situations. Historical Analysis - locates a particular policy within a historical fabric What is the historical background of the policy under consideration? What historical problems led to the creation of the policy? How important have these problems been historically? How was the problem previously handled? When did the policy originate? How has the original policy changed over time? What is the legislative history of the policy? Description of the Problem What is the nature of the problem? How widespread is the problem? How many people are affected by the problem? Who is affected and how? What are the causes of the problem? How will the policy help to address the problem? Description of the Policy How is the policy intended to work? What resources or opportunities are provided (e.g., power, cash, in-kind services, goods, etc.) Who will be covered by the policy and how (universal vs. selective, means testing, etc.) How will the policy be implemented? What at the long and short term goals and outcomes of the policy? Who will administer the policy? Who will fund the policy long term and short term? Who oversees, evaluates, and coordinates the policy? What are the criteria, formal or informal that will be used to determine whether the policy is effective? How long will the policy be in existence? What is the knowledge base or scientific grounding on which the policy rests? Policy Analysis Are the goals of the policy legal? Are the goals of the policy just and democratic? Do the goals of the policy contribute to greater social equality? Do the goals of the policy contribute to a better quality of life for the target population? Will the goals adversely affect the quality of life of the target group? Does the policy contribute to positive social relations between the target population and the overall society? Are the goals of the policy consistent with the values of professional social work? What are the hidden ideological assumptions contained within the policy? How is the target population viewed in the context of the policy? What social vision, if any, does the policy contain? Does the policy encourage the continuation of the status quo or does it represent a radical departure? Who are the major beneficiaries of the policy-the target population or some other group? In whose best interest is the policy? Is the policy designed to foster real social change or merely to placate a potentially insurgent group? Political Feasibility Which groups will oppose and which groups will support this particular policy? What is the constituency and power base of these groups? Is a large segment of the public concerned about the policy? Do people feel that they will be directly affected by the policy? Does the policy address a problem that is considered to be a major political issue? Does the policy threaten fundamental social values? Is the policy compatible with the present social and political climate? What is the general public sentiment toward the policy? What is the possibility that either side will be able to marshal public sentiment for or against the policy? Which social welfare agencies, institutions, organizations support or oppose the policy? What is the relative strength of each group? How strong is their support or opposition to the policy? What are the major federal, state, or local agencies affected by this policy? How are they affected? Economic Feasibility What is the minimum level of funding required for the successful implementation of the policy? Does adequate funding for the policy currently exist? What is the public sentiment toward reallocating resources for the policy? Is the funding called for by the policy adequate? What are the future funding needs of the policy likely to be? Administrative Feasibility Is the policy likely to accomplish what its creators intended? Is the policy broad enough to accomplish its stated goals? Will the benefits of the policy reach the target group? Are the side effects of the policy likely to cause other problems? What ramifications does the policy have for the nontarget sector? Unintended consequences? Is this policy important enough to justify the expenditure of scarce resources? Are there other areas where resources could be better used? Will the new policy provide results that are better than either the present policy or no policy at all? Is it advantageous to enlarge or modify the present policy as opposed to creating a new one? Can an alternative policy provide better results at lower cost? What alternative policies could be created that would achieve the same results and how do they compare with each other and the proposed policy? Final Key Questions Is the proposed policy workable and desirable? What, if any, modifications should be made in the policy? Does the policy represent a wise use of resources? Are there alternative policies that would be preferable? How feasible is the implementation of the policy? What barriers, if any, are there to the full implementation of the policy? Gilbert, Specht, & Terrell Model Choice Analysis – four major dimensions of choice: What are the bases of social allocation? What are the types of social provisions to be allocated? What are the strategies for the delivery of these provisions? What are the ways to finance these provisions? Allocation and Provision Who gets what? Allocations address “who” “The bases of social allocations refer to the choices among the various principles on which social provisions are made accessible to particular people and groups in society.” The “what” is a choice – in cash or in kind, power, vouchers, opportunities Delivery and Finance How? “Delivery strategies refer to the alternative organizational arrangements among providers and consumers of social welfare benefits in the context of local community systems. “Funding choices involve questions concerning the source of funds and the fashion in which funds flow from the point of origin to the point of service provision.” Values in the Quest for Distributive Justice Equality – same treatment of everyone – to all an equal share Equity – same treatment of similar persons – to each according to his/her merit or virtue; a sense of fair treatment Adequacy – the desirability of providing a decent standard of physical and spiritual well being Organizations and Policy Policies are developed and implemented through organizations. We can think of organizations at various levels, from small, private agencies through large government organizations to society as a whole. Four separate streams run through organizations: problems, solutions, participants, and choice opportunities. The streams are independent of each other. (Kingdon, J.W. (2003). Agendas, alternatives, and public policies (2nd ed.). New York: Longman.) Policy changes are necessarily made through organizations. (Think about how “international policy” is developed and implemented – and about what happens when major players decide not to play.) Policy Advocacy Efforts to change policy are addressed through what social work calls policy advocacy (which is related to but different from client advocacy). Models of Political Advocacy (Haynes, K.S., & Mickelson, J.S. (1997). Affecting change: Social workers in the political arena (3rd ed.). New York: Longman.) Institutional Model - Examines the structures of government institutions and the relationships among them and the relationships between them and policy content. For example, delivering services through county agencies versus state agencies has implications for service, accountability, etc. Process Model - Views policy as a political activity and examines how decisions are made. Group Theory Model - Examines how groups join forces to influence policy. Elite Theory Model - Examines the preferences and values of the governing elite and seeks to frame policies so they appeal to their interests. Rational Model - Examines cost/benefit ratios. Incremental Model - Views policies as built on previous policies and seeks incremental changes. Haynes & Mickelson specify four techniques for evaluating policies [but note that these are elements of evaluation, not techniques.] Effort – Assesses costs Quality – Assesses standards [Note that this is not outcomes.] Effectiveness – Assesses outcomes [but often only assesses outputs] Efficiency – Assesses cost per outcome Policy Practice Bruce Jansson outlines a model of “policy” that he considers a kind of social work practice that requires specific knowledge and skills just as other areas of social work practice do Jansson’s Model Social policy is “a collective strategy to address social problems.” Policies include (1) official, written policies, (2) informal, unwritten policies, (3) personal orientations toward a policy, and (4) personal policy actions (actualized policy). Policy practice is the “efforts to influence the development, enactment, implementation, or assessment of social policies.” Four skills of policy practice: (1) analytic skills, (2) political skills, (3) interactional skills, and (4) values-clarification skills. Six tasks of policy practice: (1) setting agendas, (2) defining problems, (3) making proposals, (4) enacting policy, (5) implementing policy, and (6) assessing policy. (From Jansson, B.S. (1994). Social policy: From theory to practice. Pacific Grove, CA: Brooks/Cole.) Six Tasks of Policy Practitioners Agenda-setting Problem-analyzing Proposal-writing Policy-enacting Policy-implementing Policy-assessing [Note subtle difference from the list above.] Jansson’s Framework for Policy Advocacy Contextual Factors: Constraints Agendasetting task Problemanalyzing task Policyenacting task Proposalwriting task Policyimplemen ting task Policyassessing task Contextual factors: Opportunities Feedback Jansson lists a four major categories of Policy Competencies: political competencies, analytic competencies, interactional competencies, and value-clarifying competency. Political competencies Using the mass media Taking a personal position Advocating a position with a decision maker Seeking positions of power Empowering others Orchestrating power on decision makers Finding resources to fund advocacy projects Developing and using personal power resources Donating time/resources to an advocacy group Advocating for the needs of a client Participating in a demonstration Initiating litigation to change policies Participating in a political campaign Voter registration Analytic competencies Developing a proposal Calculating trade-offs Doing force field analysis Using social science research Conducting a marketing study Using the Internet Working with budgets Finding funding sources for specific projects Diagnosing audiences Designing a presentation Diagnosing barriers to implementation Designing strategy to improve implementation Developing political strategy Analysung the context of policies and issues Designing policy assessments Selecting a policy practice style Interactional competencies Coalition building Making a presentation Building personal power Task group formation and maintenance Managing conflict Value-clarifying competency Engaging in ethical reasoning Jansson says there are three styles of policy practice: political style, analytical style, and value-based style. From Jansson, B. S. (1999). Becoming an effective policy advocate. Pacific Grove, CA: Brooks/Cole Publishing. Legislative Analysis Flynn’s Model of Legislative Analysis (Flynn, J.P. (1992). Social agency policy: Analysis and presentation for community practice. Chicago: Nelson-Hall.) •Must answer the standard set of who, what, when, where, and why (the 5 W’s) •A good legislative analysis is not a simplistic summary of complex events •It is not a dissertation •It must consider a wide range of issues in depth but must be compact and to the point Format for Legislation Analysis Statement of the Policy Proposition(s)/Provision(s) •Begin with a clear, uncluttered, and brief statement of the law, rule, policy, proposition, or guideline that is being proposed •State in 1 or 2 sentences and avoid jargon and reference to concepts that would be unknown to readers The Proposers •Identify the person(s) or group(s) sponsoring the policy proposal Authority or Legitimacy •Identify the source of authority or legitimacy for the existing and proposed action that has a bearing upon the action to be taken •Statute •Court ruling •Ordinance •Board directive •Executive order •Administrative directive •Licensing requirement General Concepts •Main body of the analysis •Enumerate and clarify the concepts that particularly relate to this particular proposal •Summarize the shape and nature of the problem that exists or characterize the proposal offered as a remedy •Make clear: •Why this particular approach is proposed •How the methods of means proposed are presumed to be suitable for this matter •Present factual data •Explicit discussion of the value considerations •How is the problem stated? •What are the implications of the means to be employed if approval or passage is obtained •How does this depart from or is in line with prior conceptualizations of the problem •Bring out facts found in the background data while giving focus to the central issues Intended and Possible Unintended Effects •Be fair and objective about the intended and possible unintended effects upon the target, client, and service systems •What is the potential ripple effect on rules, guidelines, companion policies? •What are the implications for other requirements or programs associated with the proposal? Fiscal Implications •Shed light on the revenue and expenditure aspects of the proposal •Discuss the fiscal implications of not taking action Advantages and Disadvantages •List concisely the arguments both for and against the proposal (unless this is a persuasive analysis) •Identify which groups and organizations have taken positions for or against the proposal or any of its provisions Recommendations •Depending upon the task given to the policy analyst, this is the only place where the analysis takes a position •Depends on who commissioned the analysis – know your audience •You may be expected to take a position and have the right to make recommendations but these must be identified separate from the rest of the analysis Author’s Identity •Identify the author of the analysis so that you may be contacted if further information is needed Debate Guidelines A debate is a formal way of testing an idea or proposition. In debate, the idea is called the resolution. In policy debate, the resolution takes the form: Resolved: That an entity should take an action. The 2002 – 2003 policy debate topic illustrates this: Resolved: That the United States federal government should substantially increase public health services for mental health care in the United States. One side, called the affirmative, has the duty to affirm or support the resolution. The affirmative side presents a case that proposes a plan and reasons for adopting the plan. In the affirmative speeches, debaters typically show a need for the plan, describe the plan, and demonstrate the advantages of the plan. Debaters often craft their speeches with an eye toward judging criteria, of which there are many. One judging system uses what are called stock issues. The stock issues are: 1. Topicality – Does the case reasonably adhere to the topic as delimited by the resolution? 2. Significance – Is there a significant problem that justifies changing the present system? 3. Inherency – Is there an inherent barrier in the current system that keeps it from solving the problem indicated in the affirmative case? Alternatively stated, is the current system inherently flawed or does it just need repair? 4. Solvency – Would the proposed plan solve the problem better than the present system? 5. Advantages – Do the advantages of the proposal outweigh the disadvantages of the proposal? To win in this judging system, the affirmative case must receive a yes answer to every one of those questions. The negative side wins if the judge answers any question with no. There are other judging systems, but the stock issues provide a good structure for conceptualizing the affirmative case. The other side, called the negative, because its job is to negate the plan offered by the affirmative side, presents a case that either upholds the status quo, i.e. shows that the affirmative side’s plan should not be supported, or that another plan is superior to the one proposed by the affirmative side. Note that the negative side does not have to negate the resolution. It simply has to negate the plan offered by the affirmative side. An illustration will clarify. Let’s say that the affirmative side proposes a plan that the federal government should improve mental health by ending compulsory education because doing so would make kids happy, and being happy is essential to good mental health. The negative side could easily show the weaknesses in that plan without rejecting the resolution itself. Because the affirmative side has the responsibility of supporting the resolution, the affirmative side goes first and last. Following is a list of the order of speeches for our inclass debates: Affirmative Constructive Cross Examination Negative Constructive Cross Examination 1st Affirmative Rebuttal Negative Rebuttal 2nd Affirmative Rebuttal - 6 minutes – Speaker A - 3 minutes – Speaker B questions speaker A - 7 minutes – Speaker B - 3 minutes – Speaker A questions speaker B - 4 minutes – Speaker A - 6 minutes – Speaker B - 3 minutes – Speaker A Speaker A has the following responsibilities: introduce the resolution, describe the problem, define terms in the resolution, demonstrate a need for a plan, and present the plan. Speaker B has the responsibility of negating the plan proposed by Speaker A. There are many ways to do this. Some common techniques used by the negative speaker include: proposing another definition of the problem, offering alternative definitions of terms, denying the need for the plan, pointing out the inability of the plan to meet the need, denying the need for any plan by defending the status quo, and offering a counterplan. Speaker B may also ask for clarification and specification of the plan. In the second affirmative speech, Speaker A has two major tasks: review the cases presented by each side while pointing out the major areas of conflict (called clash in debate jargon), and respond to the attacks made by Speaker B. Additionally, speaker A must demonstrate that the plan proposed in the first speech will solve the problem and that the plan will do so without causing more problems than it solves. In the second negative speech, Speaker B reviews the areas of conflict and restates the negative position. Speaker B goes on to attack the plan. There are many strategies. Common strategies include denying that the plan solves the problem, denying that the plan is workable, or asserting that the plan would cause more problems than it would solve. In the third affirmative speech, Speaker A responds to the negative rebuttal, summarizes the issues, and makes a final defense of the plan. Cross examination provides an opportunity to clarify any points just raised, however the skillful debater also uses cross examination to advance his or her side of the debate. This is accomplished by asking questions for which the other side has no adequate answer, that reveal weaknesses in the affirmative case, or the answers to which can later be used by the cross examiner to bolster his or her side of the argument. The questioner should be cautious in asking questions, however, because the answers may serve to bolster the opponents’ case. Generally, a questioner should ask a question only if he anticipates that the answer will support his side of the debate. Rebuttal speeches provide the opportunity to defend the position each side has laid out. No new arguments may be introduced in rebuttal speeches. As mentioned previously, there are many criteria by which one may judge a debate. In addition to the stock issues system mentioned above, another is the policy maker system. This system is built on the idea that judges should decide debates much as legislators would, i.e. the affirmative side wins if the plan is topical and its advantages outweigh the disadvantages presented by the negative. Another system awards the win to the side that scores the most points according to a predetermined list of criteria. In addition to the many systems judges may use to select a winner, there are theories that influence judging. One theory holds that the judge should be a blank slate (tabula rasa) and should judge only according to what each side says in the debate. Another theory holds that the judge is a critic, that he or she critically evaluates the quality of the arguments each side makes, and makes a decision based on the quality of those arguments. It becomes apparent that judging the winner of a debate can be a challenge. For the purposes of this class, we will not be selecting a winner, however students are well advised to consider the quality of their arguments. Sources: Eisenberg, A.M, & Ilardo, J.A. (1980). Argument: A guide to formal and informal debate (2nd ed.). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. Freeley, A.J. (1966). Argumentation and debate: Rational decision making (2nd ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth. Kruger, A.N. (1960). Modern debate: Its logic and strategy. New York: McGraw-Hill. Musgrave, G.M. (1957). Competitive debate: Rules and procedures (3rd ed.). New York: Wilson. Thomas, D.A., & Hart, J. (1987). Advanced debate: Readings in theory practice and teaching (2nd ed.). Lincolnwood, IL: National Textbook.