Inter-American Human Rights System

advertisement

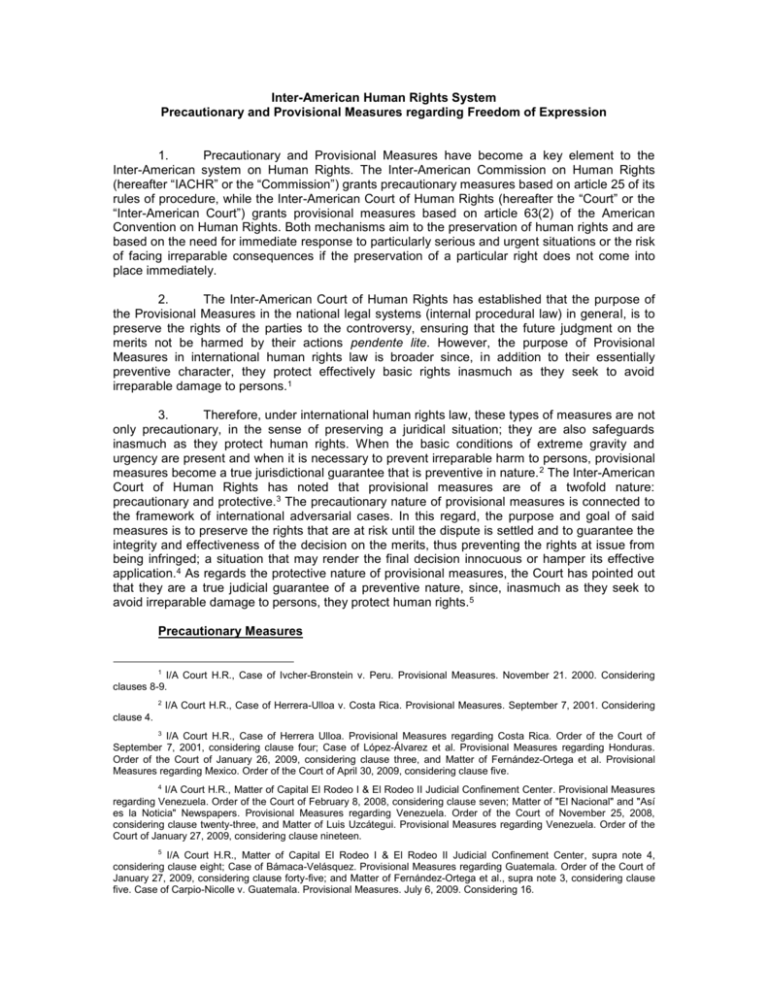

Inter-American Human Rights System Precautionary and Provisional Measures regarding Freedom of Expression 1. Precautionary and Provisional Measures have become a key element to the Inter-American system on Human Rights. The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (hereafter “IACHR” or the “Commission”) grants precautionary measures based on article 25 of its rules of procedure, while the Inter-American Court of Human Rights (hereafter the “Court” or the “Inter-American Court”) grants provisional measures based on article 63(2) of the American Convention on Human Rights. Both mechanisms aim to the preservation of human rights and are based on the need for immediate response to particularly serious and urgent situations or the risk of facing irreparable consequences if the preservation of a particular right does not come into place immediately. 2. The Inter-American Court of Human Rights has established that the purpose of the Provisional Measures in the national legal systems (internal procedural law) in general, is to preserve the rights of the parties to the controversy, ensuring that the future judgment on the merits not be harmed by their actions pendente lite. However, the purpose of Provisional Measures in international human rights law is broader since, in addition to their essentially preventive character, they protect effectively basic rights inasmuch as they seek to avoid irreparable damage to persons.1 3. Therefore, under international human rights law, these types of measures are not only precautionary, in the sense of preserving a juridical situation; they are also safeguards inasmuch as they protect human rights. When the basic conditions of extreme gravity and urgency are present and when it is necessary to prevent irreparable harm to persons, provisional measures become a true jurisdictional guarantee that is preventive in nature. 2 The Inter-American Court of Human Rights has noted that provisional measures are of a twofold nature: precautionary and protective.3 The precautionary nature of provisional measures is connected to the framework of international adversarial cases. In this regard, the purpose and goal of said measures is to preserve the rights that are at risk until the dispute is settled and to guarantee the integrity and effectiveness of the decision on the merits, thus preventing the rights at issue from being infringed; a situation that may render the final decision innocuous or hamper its effective application.4 As regards the protective nature of provisional measures, the Court has pointed out that they are a true judicial guarantee of a preventive nature, since, inasmuch as they seek to avoid irreparable damage to persons, they protect human rights.5 Precautionary Measures 1 I/A Court H.R., Case of Ivcher-Bronstein v. Peru. Provisional Measures. November 21. 2000. Considering clauses 8-9. 2 I/A Court H.R., Case of Herrera-Ulloa v. Costa Rica. Provisional Measures. September 7, 2001. Considering clause 4. 3 I/A Court H.R., Case of Herrera Ulloa. Provisional Measures regarding Costa Rica. Order of the Court of September 7, 2001, considering clause four; Case of López-Álvarez et al. Provisional Measures regarding Honduras. Order of the Court of January 26, 2009, considering clause three, and Matter of Fernández-Ortega et al. Provisional Measures regarding Mexico. Order of the Court of April 30, 2009, considering clause five. 4 I/A Court H.R., Matter of Capital El Rodeo I & El Rodeo II Judicial Confinement Center. Provisional Measures regarding Venezuela. Order of the Court of February 8, 2008, considering clause seven; Matter of "El Nacional" and "Así es la Noticia" Newspapers. Provisional Measures regarding Venezuela. Order of the Court of November 25, 2008, considering clause twenty-three, and Matter of Luis Uzcátegui. Provisional Measures regarding Venezuela. Order of the Court of January 27, 2009, considering clause nineteen. 5 I/A Court H.R., Matter of Capital El Rodeo I & El Rodeo II Judicial Confinement Center, supra note 4, considering clause eight; Case of Bámaca-Velásquez. Provisional Measures regarding Guatemala. Order of the Court of January 27, 2009, considering clause forty-five; and Matter of Fernández-Ortega et al., supra note 3, considering clause five. Case of Carpio-Nicolle v. Guatemala. Provisional Measures. July 6, 2009. Considering 16. 4. Precautionary measures are based on the provisions of article 25 of the Commission’s Rules of Procedure. Section 1 of said article states: “In serious and urgent situations, the Commission may, on its own initiative or at the request of a party, request that a State adopt precautionary measures to prevent irreparable harm to persons or to the subject matter of the proceedings in connection with a pending petition or case.”6 5. These measures are adopted out of a need (i) to avert grave, imminent, or irremediable harm to one of the rights protected in the American Convention of Human Rights, or (ii) to maintain jurisdiction in the case and so the subject of the action does not disappear. 7 The IACHR may request information from the interested parties concerning any matter related to the adoption and observance of the precautionary measures. In any event however, the granting of such measures and their adoption by the State shall not constitute any prejudgment on the merits of the case.8 6. The Office of the Special Rapporteur has worked with the IACHR Protection Group with regard to recommendations on the adoption of precautionary measures in the area of freedom of expression. In this regard, the IACHR has requested on multiple occasions that Member States adopt precautionary measures to protect the right to freedom of expression. It did so, for example, in the cases of (i) Matus Acuña v. Chile, 9 (ii) Herrera Ulloa v. Costa Rica;10 (iii) López Ulacio v. Venezuela;11 (iv) Peña v. Chile;12 (v) Globovisión v. Venezuela;13 (vi) Tristán Donoso v. Panama;14 (vii) Yáñez Morel v. Chile,15 (viii) Pelicó Pérez v. Guatemala,16 and (ix) Rodríguez Castañeda17 v. Mexico.18 6 Rules of Procedure of the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights. October 28 – November 13, 2009. Article 25. Available at: http://www.cidh.oas.org/Basicos/English/Basic18.RulesOfProcedureIACHR.htm 7 IACHR, Annual Report of the Office of the Special Rapporteur for Freedom of Expression 2010. OEA/Ser.L/V/II.Doc. 5. March 4, 2011. Chapter I, para. 26. Available at: http://www.oas.org/en/iachr/expression/docs/reports/RFE.ANNUAL-REPORT-2010.pdf 8 IACHR, Annual Report 2010. OEA/Ser.L/V/II. Doc. 5, rev. 1. 7 March 2011. Chapter III, C1, para. 7. Available at: http://www.cidh.oas.org/annualrep/2010eng/TOC.htm 9 IACHR decision issued June 18, 1999, and expanded on July 19, 1999, requesting that the Chilean government adopt precautionary measures for the benefit of Bartolo Ortiz, Carlos Orellana, and Alejandra Matus, in light of detention orders against the first two and an order prohibiting the distribution and sale of a book, stemming from the publication of the Libro Negro de la Justicia Chilena [Black Book of Chilean Justice], written by Mrs. Matus. 10 IACHR decision of March 1, 2001, requesting that the State of Costa Rica adopt precautionary measures for the benefit of journalist Mauricio Herrera Ulloa and the legal representative of the newspaper La Nación, who had received criminal and civil convictions due to the publication of reports against an official in the Costa Rican Foreign Service, with the sentences not having fully materialized at the time the measures were adopted. 11 IACHR decision of February 7, 2001, requesting that the State of Venezuela adopt precautionary measures for the benefit of journalist Pablo López Ulacio, who had accused a businessman of benefiting from state insurance contracts in the context of a presidential campaign. The journalist was ordered detained and prohibited from publicly mentioning the businessman in the daily La Razón. 12 IACHR decision of March 2003, requesting that the State of Chile adopt precautionary measures, for the benefit of writer Juan Cristóbal Peña, by lifting the judicial order seizing and withdrawing from circulation a biography of a popular singer who sought the order on the grounds that the account was considered grave slander. 13 IACHR decisions of October 3 and October 24, 2003, requesting that the State of Venezuela suspend administrative decisions to seize operating equipment from the Globovisión television station and that it guarantee an impartial and independent trial in this case. 14 IACHR decision of September 15, 2005, requesting that the State of Panama suspend a detention order against Santander Tristán Donoso, stemming from his failure to comply with a monetary fine imposed for the alleged commission of the crime of libel and slander, after Mr. Tristán Donoso denounced that the Prosecutor General of the Nation had divulged taped conversations telephone calls. 15 IACHR decision adopted following the presentation of an individual petition in 2002, in the name of Eduardo Yáñez Morel, who was prosecuted for committing the crime of desacato, having severely criticized the Supreme Court of Justice on a television program in 2001. 7. Most of these cases can be associated with the first hypothesis for granting precautionary measures the need to avert grave, imminent, or irremediable harm to one of the rights protected in the American Convention of Human Rights, particularly freedom of expression, life and integrity. While the last case, Rafael Rodríguez Castañeda v. Mexico, decided on July 3, 2008, granted a request for precautionary measures to preserve said journalist’s right to access information; following the second hypothesis: the need to maintain jurisdiction in the case and so the subject of the action does not disappear. 8. In this particular case the request was seeking precautionary measures associated with petition P492/08 which alleged, inter alia, that the courts’ refusal to provide access to leftover ballots, unused ballots, ballots declared to be valid and those nullified in the election held on July 2, 2006, before those ballots were destroyed, was a violation of Article 13 of the American Convention. The IACHR asked the Mexican state to suspend plans to destroy the ballots until it was able to rule on the merits of the petition filed by Rafael Rodríguez Castañeda. 19 Precautionary measures were granted in order to safeguard the object of the petition and emphasizing the fact that granting of said measures does not imply any prejudgment on the merits of the complaint. Provisional Measures 9. The Court’s ability to grant provisional measures is based on Article 63(2) of the American Convention on Human Rights, which states: “In cases of extreme gravity and urgency, and when necessary to avoid irreparable damage to persons, the Court shall adopt such provisional measures as it deems pertinent in matters it has under consideration. With respect to a case not yet submitted to the Court, it may act at the request of the Commission.” 10. In this sense, the Convention requires that for the Court to order the adoption of provisional measures three conditions must be met: i) “extreme gravity”; ii) “urgency”, and iii) an attempt to “avoid irreparable damage to persons.” These three conditions coexist and must be present in all the situations in which the intervention of the Tribunal is requested. 20 11. Additionally, Article 27 of the Rules of Procedure of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights indicates, inter alia, that: “1. At any stage of proceedings involving cases of extreme gravity and urgency, and when necessary to avoid irreparable damage to persons, the Court may, on its own motion, order such provisional measures as it deems appropriate, pursuant to Article 63(2) of the Convention. 2. With respect to matters not yet submitted to it, the Court may act at the request of the Commission.” 12. Therefore, the Court may act on its own motion or when requested by the IACHR. Do to its conventional origin, provisional measures can often have a greater binding effect than precautionary measures and a broader ability to protect any right under the American 16 IACHR decision of November 3, 2008, in which the IACHR requested that the State of Guatemala take the measures necessary to guarantee the life and humane treatment of Pelicó and his family, because of the grave and constant threats received by the journalist as a result of his investigations and publications on drug trafficking. 17 IACHR decision adopted on July 3, 2008, for the purpose of preventing the destruction of electoral ballots from the 2006 presidential elections in Mexico. 18 IACHR, Annual Report of the Office of the Special Rapporteur for Freedom of Expression 2010. OEA/Ser.L/V/II.Doc. 5. March 4, 2011. Chapter I, para. 26. Available at: http://www.oas.org/en/iachr/expression/docs/reports/RFE.ANNUAL-REPORT-2010.pdf 14. 19 IACHR. Precautionary Measures 2008. Available at: http://cidh.oas.org/medidas/2008.sp.htm 20 I/A Court H.R., Case of Carpio-Nicolle et al. v. Guatemala. Provisional Measures. July 6, 2009. Considering Convention as long as it seeks to avoid irreparable damage to persons. Both the Court and the IACHR have used provisional and precautionary measures to protect freedom of expression. However, the Court and the IACHR don’t always agree. 13. So far, both organs of the Inter-American system have agreed on issues where the protection of freedom of expression is strongly linked to the protection of the life and integrity of a person. It’s been such in cases like Luisiana Ríos et al V. Venezuela; “El Nacional” and “Así es la Noticia” newspapers V. Venezuela; and Globovisión Television Station V. Venezuela. In these three cases journalist, media outlets and media outlets employees were granted protective measures to their life, security and freedom of expression by the Inter-American Court at the request of the IACHR. The Court assumed that the evidence submitted in each particular case demonstrated prima facie the existence of a situation of extreme gravity and urgency regarding the life and physical safety of the alleged victims. 21 14. In 1998, the IACHR adopted precautionary measures in the case of IvcherBronstein V. Peru, a naturalized citizen of Peru who was a majority shareholder in a television channel that aired a program that was severely critical of certain aspects of the Peruvian government and as a result of these reports, the State revoked the petitioner’s Peruvian citizenship and removed his shareholding control of the channel. The Commission in this opportunity requested that the State of Peru refrained from taking or executing any action or measure that could worsen Mr. Ivcher-Bronstein situation, including ordering his capture by Interpol. Two years later, the Court on its own motion decided to grant provisional measures based on the final arguments of the Commission in public hearing on the matter held on November 20-21, 2000. The Court established prima facie the existence of threats against the personal integrity and the legal guarantees of Mr. Baruch Ivcher-Bronstein, an alleged victim in the case, as well as against those of certain members of his family, certain members of his companies, and other persons related to the events that gave rise to the instant case. Adding that the prima facie case assessment standard and the application of presumptions vis-à-vis the needs for protection, have served as a basis for provisional measures adopted by the court on different occasions.22 In this decision the Court not only protected life and integrity but also the legal guarantees of the beneficiaries.23 15. In the case of Herrera Ulloa v. Costa Rica, a journalist who had published several articles reproducing information from various European newspapers on alleged illegal conduct by a Costa Rican diplomat was convicted by the State on four defamation charges. The IACHR 21 I/A Court H.R., Matter of "Globovisión" Television Station regarding Venezuela. Provisional Measures. September 4, 2004. I/A Court H.R., Matter of "El Nacional" and "Así es la Noticia" Newspapers regarding Venezuela. Provisional Measures. July 6, 2004. I/A Court H.R. Matter of Luisiana Ríos et al. regarding Venezuela,. Provisional Measures. November 27, 2002. 22 (cfr., inter alia, Order of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights of November 17, 1999, Provisional Measures in the Digna Ochoa and Plácido et al. Case, Considering No. 5; Order of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights of June 3, 1999, Provisional Measures in the Cesti-Hurtado Case, Considering No. 4; Order of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights of May 27, 1999, Provisional Measures in the James et al. Case, Considering No. 8; Order of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights of June 19, 1998, Provisional Measures in the Clemente-Teherán et al. Case, Considering No. 5; Order of the President of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights of July 22, 1997, Provisional Measures in the Álvarez et al. Case, Considering No. 5; Order of the President of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights of August 16, 1995, Provisional Measures in the Blake Case, Considering No. 4; Order of the President of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights of July 26, 1995, Provisional Measures in the Carpio-Nicolle Case, Considering No. 4; Order of the President of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights of June 4, 1995, Provisional Measures in the Carpio-Nicolle Case, Considering No. 5; Order of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights of December 7, 1994, Provisional Measures in the Caballero-Delgado and Santana Case, Considering No. 3; Order of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights of June 22, 1994, Provisional Measures in the Colotenango Case, Considering No. 5; Order of the President of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights of April 7, 2000, Provisional Measures in the Constitutional Court Case, Considering No. 7; Order of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights of August 18, 2000, Provisional Measures in the Haitians and Haitian-origin Dominican Persons in the Dominican Republic Case, Considering No. 5 and 9; Order of the President of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights of October 9, 2000, Provisional Measures in the Paz de San José de Apartadó Community Case, Considering No. 4). 23 I/A Court H.R., Case of Ivcher-Bronstein v. Peru. Provisional Measures. November 21, 2000. granted precautionary measures on behalf of Mauricio Herrera Ulloa and Fernán Vargas Rohrmose, the legal representative of the newspaper La Nación. The Commission, basing itself on a recommendation from the Special Rapporteur for Freedom of Expression, asked the State of Costa Rica to suspend execution of the criminal sentence until the Commission could examine the case; to refrain from any act tending toward the inclusion of the journalist Herrera Ulloa in the Costa Rican Judicial Register of Criminals; and to refrain from any act or action affecting the right of free expression of the aforesaid journalist or of the newspaper La Nación. The State’s ineffectiveness in protecting the free expression of the beneficiaries, together with the fact that the Costa Rican courts failed to implement the timely request for precautionary measures, leaded the Commission to ask the Inter-American Court of Human Rights to adopt provisional measures. The Court granted the measures asking the State of Costa Rica to abstain from executing any action that would alter the status quo in the case sub judice.24 Both the Court and the Commission understood the necessity to protect the beneficiaries from irreparable damages. 16. On the other hand, in the case of Castañeda Gutman V. Mexico the Federal Electoral Institute notified Mr. Castañeda Gutman that he could not be registered as a political candidate on the basis that, according to the Mexican Constitution, “political parties have the purpose of affording [citizens] access to the exercise of public power and the Federal Code of Electoral Institutions and Procedures (COFIPE) provides that it shall fall exclusively to national political parties to request the registration of candidates for popularly elected offices.” The InterAmerican Commission determined that this situation could lead to irreparable damage to the exercise of political rights and consequently asked the Mexican Government to adopt precautionary measures to allow the provisional registration of Mr. Jorge Castañeda Gutman as a candidate for the office of President of the Mexican Republic. Later, when the IACHR requested provisional measures from the Inter-American Court of Human Rights, the Court concluded that in order to adopt provisional measures it could only take into consideration the strictly established elements of extreme gravity, urgency and need to avoid irreparable damages to a person and in the particular case the granting of a provisional right to register as a candidate for the office of President of the Mexican Republic would adversely affect the merits of the petition, as said registration was the main issue claimed in the petition. Therefore, the Court resolved to dismiss the request for provisional measures as inadmissible. 25 17. In the case of Belfort Istúriz et al V. Venezuela, the IACHR requested provisional measures before the Inter-American Court in favor of the owners and four journalists of a chain of five radio stations known as “Circuito Nacional Belfort” [Belfort Nationa Circuit]. In the frame of a mayor legislative election the State revoked the license of at least 34 radio stations mostly know for its critical voice and often reassigned its frequencies to stations allied with State points of views. The Commission understood there was a need for provisional measures to protect freedom of expression in both its individual and collective dimensions. It argued that undermining free speech on a crucial moment, such as the electoral process taking place in 2010 could cause irreparable damages regardless of the reparations the Court could eventually allow if the petition was resolved in favor of the beneficiaries. The Inter-American Court however, decided not to grant provisional measures in this particular case. After reminding the fact that in order to grant provisional measures three basic conditions must coexist and be present in all the situations in which the intervention of the Tribunal is requested: i) “extreme gravity”; ii) “urgency”, and iii) an attempt to “avoid irreparable damage to persons.” The Court found that the elements of ‘extreme gravity’ and ‘urgency’ were duly accounted for, however it considered that the Commission failed to proof the irreparability of the damage against the free expression of the alleged beneficiaries and could only proof reparable damages against their property. As for the freedom of expression of society as a whole, the Court considered that provisional measures could not be granted since the beneficiaries would have been undetermined and unidentifiable.26 24 I/A Court H.R., Case of Herrera-Ulloa v. Costa Rica. Provisional Measures. April 6, 2001 and May 23, 2001. 25 I/A Court H.R., Matter of Castañeda-Gutman regarding Mexico. Provisional Measures. November 25, 2005. 26 I/A Court H.R., Matter of Belfort Istúriz et al. regarding Venezuela. Provisional Measures. April 15, 2010.