Analysing “Analysis and Community”

advertisement

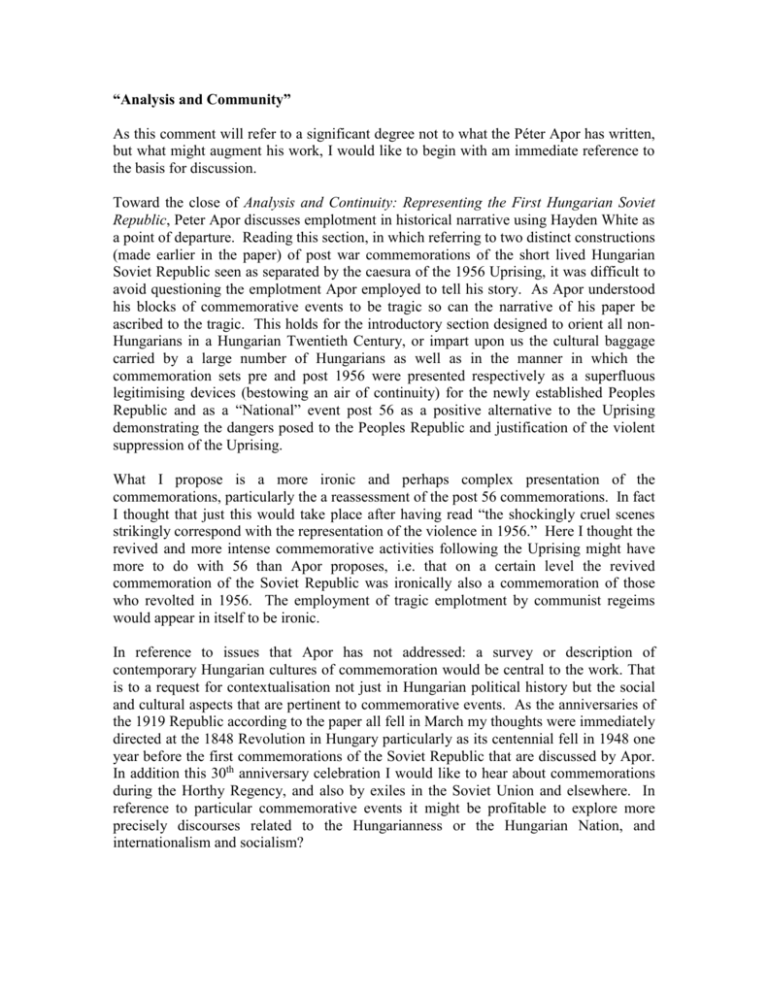

“Analysis and Community” As this comment will refer to a significant degree not to what the Péter Apor has written, but what might augment his work, I would like to begin with am immediate reference to the basis for discussion. Toward the close of Analysis and Continuity: Representing the First Hungarian Soviet Republic, Peter Apor discusses emplotment in historical narrative using Hayden White as a point of departure. Reading this section, in which referring to two distinct constructions (made earlier in the paper) of post war commemorations of the short lived Hungarian Soviet Republic seen as separated by the caesura of the 1956 Uprising, it was difficult to avoid questioning the emplotment Apor employed to tell his story. As Apor understood his blocks of commemorative events to be tragic so can the narrative of his paper be ascribed to the tragic. This holds for the introductory section designed to orient all nonHungarians in a Hungarian Twentieth Century, or impart upon us the cultural baggage carried by a large number of Hungarians as well as in the manner in which the commemoration sets pre and post 1956 were presented respectively as a superfluous legitimising devices (bestowing an air of continuity) for the newly established Peoples Republic and as a “National” event post 56 as a positive alternative to the Uprising demonstrating the dangers posed to the Peoples Republic and justification of the violent suppression of the Uprising. What I propose is a more ironic and perhaps complex presentation of the commemorations, particularly the a reassessment of the post 56 commemorations. In fact I thought that just this would take place after having read “the shockingly cruel scenes strikingly correspond with the representation of the violence in 1956.” Here I thought the revived and more intense commemorative activities following the Uprising might have more to do with 56 than Apor proposes, i.e. that on a certain level the revived commemoration of the Soviet Republic was ironically also a commemoration of those who revolted in 1956. The employment of tragic emplotment by communist regeims would appear in itself to be ironic. In reference to issues that Apor has not addressed: a survey or description of contemporary Hungarian cultures of commemoration would be central to the work. That is to a request for contextualisation not just in Hungarian political history but the social and cultural aspects that are pertinent to commemorative events. As the anniversaries of the 1919 Republic according to the paper all fell in March my thoughts were immediately directed at the 1848 Revolution in Hungary particularly as its centennial fell in 1948 one year before the first commemorations of the Soviet Republic that are discussed by Apor. In addition this 30th anniversary celebration I would like to hear about commemorations during the Horthy Regency, and also by exiles in the Soviet Union and elsewhere. In reference to particular commemorative events it might be profitable to explore more precisely discourses related to the Hungarianness or the Hungarian Nation, and internationalism and socialism? One last point addresses Apor’s source criticism, or his criticism of sources created within the Communist Hungarian system on commemorations of 1919 and how these “fictions which reveal various conceptions and assumptions of their composers” differ from and other source? Secondly I would like to see the analysis of other source material not necessarily produced by the HCP. Concluding, I thank Apor for taking me upon pleasurable and thought provoking excursion back to Central Europe with his paper, and hope that my comments will be of some use. James Kaye A Response to James Kaye First of all let me express my appreciation to James` very sharp eye that pointed out several crucial issues in my paper. I am convinced that there is no fundamental disagreement between us, therefore I shall add only some remarks to his comments. First, the second part of my paper that studies a certain tragic emplotment in the commemoration of the First Hungarian Soviet Republic is under constant re-evaluation. I believe that I have not capitalized on all of its abilities in constructing a representation of communism. What James offered – to compose my own emplotment in a more ironic mode – is precisely my intention. The interrelation between the memory of 1956 and 1919 is a crucial aspect of my argument, however has not been elaborated in full scope yet. 1919 was depicted in a way derived from the interpretation of 1956 also on a level of creating figures in the narratives. A fundamental figure in the martyrology of 1919 (Latinca) was depicted according to the figure of a fallen communist high official in 1956 (Mező). By 1969 the memory of 1919 was used in order to cover the recollections of 1956. The archetypical representation of the struggle between revolution and counterrevolution connected to the history of 1919 was intended to embed the discourse on these conceptual counterparts. Second, it is justified to require a contextualization of commemoration, that is to say to describe contemporary culture of public representations of past events and survey a tradition of remembering 1919. Let me examine its possibilities. Third, I insist on that communism produced a somewhat extraordinary corpus of sources. Not in the way which could be concluded from the sentence James quoted, but rather due to a centralization and control of document producing. It is hard to find alternative sources to communism. What was produced by non-communist institutions like records of the Radio Free Europe, papers of emmigrants, the report of the UNO Committee of Five in 1956 or papers of oppositional figures were direct references to communist representations. Those could be considered as forming a sort of `enemy archives` as István Rév put it (The Open Society Archives, Budapest New York, 1999). In other words those records formed a significant part of the discourse of communism. There is no practice of power without opposition (See esp. Foucault`s History of Sexuality vol. 1. And Erwing Goffman`s Asylums). It seems that classical communism produced more thouroughly a politicization of everyday life, than other political regimes. Those attempts that were intended to object the party`s discourse necessarily got engaged in a politicized language, thereby got involved in the practice of communism itself. All this became apparent, however, only after 1989. Péter Apor