Form and the Essay

advertisement

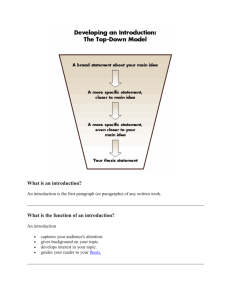

The Art of Persuasion1 The purpose of a critical (or argumentative) essay is to communicate a point from one mind to another. In writing such an essay, you must come up with an idea— your idea—and you must convincingly prove that idea to others with evidence and reasoning. That can be difficult, and awareness of the formal elements of a critical essay can help you through the difficulty. Certainly, in a course that counts for writing credit you will discuss form, and will work with, and play with, formal elements. But form in an essay is a means to an end, not an end in itself. It is certainly possible to construct an essay formally excellent in every way, and yet completely devoid of any idea. Such an essay is simply a glorious costume draped over a headless mannequin. The idea—the point towards which the formal elements work— is what gives your writing life. Moreover, every essay has its own style, and follows its own strategy. Thus no essay should be restricted to the straitjacket of the “five paragraph” format that consists of a single thesis paragraph listing three points, followed by a single paragraph for each of those three points, followed by a one-paragraph conclusion. To fulfill the single purpose of the critical essay—communicating a point to an audience—you must acknowledge that your audience has specific needs, needs that the formal elements of the essay work to satisfy. Since your audience needs a reason to read your essay in the first place, you should provide a sense of occasion at the beginning of the essay. Since your audience needs to know exactly what you’re proving, you should provide a sound thesis or controlling idea. Since your audience needs to know how you plan to support your thesis, you should provide a preview of this support, a preview that also serves as your projected organization. In the following developmental paragraphs you should develop in detail the points you listed in your preview, and in the same order. These paragraphs represent the proof that your audience will require to be convinced of your position. Occasion. Your essay might have a great point, but unless you can show your readers that your point is important to them, it will fall upon deaf ears. Audiences are essentially selfish; people generally do not have the time or the inclination to read something that they imagine to be without relevance. Consider all of the times that you began reading something and never finished because you simply could not reasonably answer the question “why should I read this?” A strong occasion will answer that question. Attract readers by showing them that the issue you explore, the problem you resolve, or the assertion you refute has significance for them. Certainly, 1 Adapted from Dr. Paul Murphy’s “Form and the Essay.” a powerful occasion can capture an audience. But do not underestimate the intelligence of your readers; capture them with substance, and not simply with flash. Thesis. Your thesis is simply a clear statement of what you plan to prove. You might consider your thesis as your conclusion: not the final words of the essay, of course, but the outcome of all the thought you have given to your subject. Therefore, coming up with a thesis is not the first step in writing an essay. Thinking is. Sometimes, instructors will ask you to submit a thesis paragraph or a thesis statement, before you submit a full draft. You make a serious mistake, however, if you assume that you can create a strong thesis without considering the shape, the intent, and the content of the full draft to follow. Your thesis establishes you as an authority on a specific subject, and unless you have thought through your subject thoroughly enough to earn that authority, you almost guarantee that every revision will start from scratch. You’d be wise to know whether you can prove a point, and to know exactly how you can prove it, before you commit yourself to proving it, because a thesis is a commitment—a contract between you and the reader. By stating the terms of your contract clearly near the outset, you demonstrate that you are well beyond the stage of “thinking through” a point; you’re showing the audience that you are ready to prove the point to others. Stating your thesis early in the essay gives both you and your audience an exact sense of the end you have in mind in the chain of reasoning that follows. Not providing a thesis, or providing a nebulous thesis, engenders confusion, not suspense; few people will voluntarily read an essay from beginning to end with little sense of direction. Give your audience a solid sense of direction by explicitly stating a thesis to be proved in the body of the essay. Analysis and argument are central to most critical writing. An analytical thesis establishes your specific idea about or interpretation of a topic. It promises to teach your audience something new about your topic—a new perspective, a way of rethinking a topic. It therefore promises something original: your idea, not a representation of someone else’s interpretation. Generally, for a thesis to be viable it should meet one or both of the following criteria: (1) it is potentially refutable (i.e. involves interpretation rather than fact); (2) and/or it explicates something otherwise obscure (for example: subtle ways in which the visual narrative of a film complements its verbal narrative). A thesis of the first type, one that is potentially refutable, often directly engages in controversy by challenging an existing point of view. A strong critical writer will welcome that challenge, not avoid it. Since such a “refutational” thesis assumes an opposition, it generally requires the writer to make clear the nature of the opposition. Ways to achieve this include starting your occasion with a quote or paraphrase of your opponent’s position. Preview/projected organization. While your thesis makes clear what point you are going to prove, your preview/projected organization makes clear to a reader exactly how you plan to prove the point. To put it simply, you give the reader a sense of your strategy. A strong preview/projected organization not only sets out your supporting ideas, but also makes clear the logical connection between those supports and your thesis. A simple list of points with no logical connection to the thesis hardly conveys any strategy at all. An effective strategy, on the other hand, demonstrates that your supports are not miniature essays in themselves, but rather are links in a chain of logic—links that together establish your thesis. There are several advantages to projecting a strategy near the beginning of the essay. For one thing, by substantiating your thesis, you give the reader true motivation for reading on. If your thesis establishes your authority, your projected organization confirms it. Moreover, you give your reader a strong sense of where you’re going in your essay, providing a sense of shape and establishing clear expectations. Some might object to setting out a projected organization for this reason, arguing that spelling out a strategy gives away too much—leaving nothing for the body of the essay. Setting out a line of reasoning, however, is not at all the same thing as developing it. Your projected organization, like your thesis, simply makes promises; the rest of the essay fulfills them. If simply stating your supporting ideas exhausts your thinking on a subject, you don’t know enough to write the essay in the first place. Another advantage of projecting a clear strategy is that it will help you, the writer, know where you’re going. It makes clear to you exactly what you must do— and, equally important, what you need not do—in developing the essay. And since your projected organization works as a brief outline, you would be wise to outline your essay in full before attempting to set out a projected organization. A final word about the preview/projected organization. Outside of fairy tales, three is not a magic number. Forcing yourself to work with three supporting points can often seriously damage your essay, either because you really have only two points, but struggle to create a third one of dubious relevance, or because you really have four, or five, or six supporting points, some of which you drop or jam together to come up with three. In focusing on a specific number of points, you’re likely to lose sight of the logical connections that unite these points into a strong chain of evidence. How many supporting points do you need in an essay? That depends completely upon the thesis you want to prove. Let the thesis shape your essay; don’t distort your essay to conform to a pre-existing sense of a “correct number” of supporting points. Developmental paragraphs. In a successful opening to a critical essay, occasion, thesis, and preview/projected organization—usually, but not always, in that order—combine into an organic whole. The developmental or body paragraphs of the essay fulfill the promise of your opening. Keep in mind that if you project a clear strategy in your introduction, your reader will expect you to keep to it in the body of the essay. If the two structures—projected and actual—are out of joint, you’ll need to change one or the other. Moreover, in order to fulfill the demands of the thesis, the body of your essay must consist of more than data, of more than simply descriptive facts. A critical essay must contain analysis. You need to explain why the facts you cite work to prove your thesis. In other words, you need to reason out your points. If you are writing a refutational essay, as noted above, you need to confront the opposition directly. There are a number of ways to counter a contrary position in your developmental paragraphs. You can demonstrate that it is misguided, illogical, irrelevant, distorted, or somehow otherwise wrong. Or, perhaps, you can show that what seems to be a contrary view is no impediment to your position. How you counter a contrary position will depend largely upon your argument. But the opposition will not go away just because you ignore it. Conclusion. In concluding an essay, many writers feel trapped between two equally unpleasant options—simply restating the point of your paper, or setting out into new territory by stating a new point. The first option can lead to a boring and perhaps even insulting conclusion: you stated a point and strategy clearly at the start, you established your point by following your strategy in the body of the essay, and now—just in case the reader didn’t get it—you repeat at length your thesis and strategy as your conclusion. One alternative would be to restate the point of your paper, but only very briefly in the opening sentence or two of the conclusion. For example: This essay hopes to have explicated how the film Memento draws on notions of language and its indeterminacy that can be traced back to the ancient sophists. What, then, should you do with the rest of your conclusion? To conclude by stating something completely new could put you in the position of having a completely new thesis to defend. Consider the following. When you set out a thesis, you are simply making a promise. By the time you reach the final word of the final body paragraph, you have kept your promise, by conveying an idea, in full, to your reader. You’ve earned the right to apply your point. You’ve earned the right to say that you’ve proved X, and that here’s what proving X should mean to the reader: here’s how knowing X should force the reader to rethink an act of Congress, or the state of affairs in Cambodia, or El Niño, or Wuthering Heights, or whatever. You’ve given the reader a new perspective. End by showing how the reader can use that new perspective.