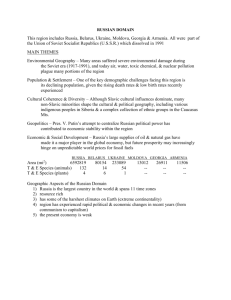

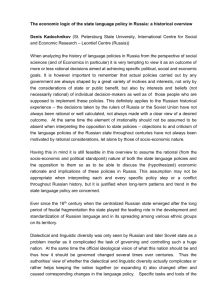

National Identity in Russia from 1961 : Traditions and

advertisement