Artifact

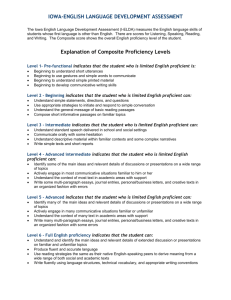

advertisement

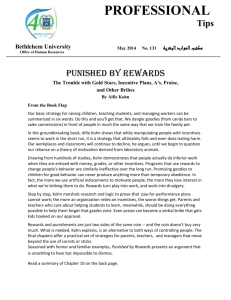

Jennifer Abbatiello Assessment Journals ***Three of the journal entries completed for the course. I did not include the journal in its entirety as it is quite lengthy. *** Module IV As far as our discussions go, I have been enjoying reading my peers’ responses and thoughts relating to assessment tools, standardized testing, and ELLs. It is so neat to hear others’ perspectives and experiences, since they differ so much from my own. I did take particular offense to a recent comment about how “sad” it is that teachers in our group discuss the state test and put importance on it. I take offense to that comment because I suppose I am one of “those” teachers that place importance on the state test. I once vowed that I would never be a teacher who “teaches to a test.” All through my education courses and my student teaching…never would I stoop so low as to even bring up the words “state test” in my classroom. I read the words of people like Alfie Kohn and listened to presenters speak on the topic and said that in my classroom we would never discuss standardized testing. I learned pretty quickly, however, that I didn’t have much choice. In Delaware, students that don’t meet the “standard” don’t move on to the next grade. So I realized that I did have to talk about the test and I had to provide the students with test prep materials, and I basically had to teach them to be a better student in third grade that I probably was in sixth grade. As Genesee and Upshur mentioned, something that tests measure besides content is how well a student can take tests. On page 143, they write, “What a test is measuring is a reflection of not only its content but also the method it employs.” This is so true – there are ways to take even the simplest multiple choice tests – first, eliminate the answer(s) (usually two) that is/are definitely wrong, then narrow down the last two and choose the best. When we do such practices, I insist that we use materials that will broaden their horizon and pique their curiosity in some way, whether it is reading about dinosaurs or sports, or anything that interests them just so it is a little more enjoyable and not a waste of time. We do these things because honestly, there’s nothing worse than the look on a child’s face when he/she has just been given his/her results from the test and he/she didn’t pass. And there’s nothing worse than the tears that follow when they realize they have to spend their summer at school. And worse than that is the fear that they will begin to hate school at the age of eight. I have been there – the tears, the frightened looks because they’re afraid they let me or their parents down - it’s horrible. Outside of the classroom, it’s easy to say that standardized testing is terrible and that we should not waste a single minute on it in our daily lessons, but when you’re actually there, it’s really a different ballgame. Do I wish I could go back to the idealized thinking that I would never have to teach about a test? Yes, I sure do, but the truth is, in today’s education field, it’s not possible. There are too many stakes to risk by not helping those kids reach those standards. Now…on to our topic for today’s journal… When Alfie Kohn came to Salisbury, I read the book and attended the presentation. He’s very good at pointing out all the negative points to standardized testing, but it’s just not getting us very far. I think it was four years ago that he came to SU, and look what’s happened since – NCLB and the push for standardized testing. So what’s the answer? Alfie Kohn discusses several important points at the specified website. I want to highlight just a couple. He says that “virtually all” specialists he knows of condemns giving standardized tests to eight and nine year olds. This hits home for me. I’ve seen how my students will completely shut down if they have a bad morning at home or if their best friend isn’t talking to them, or even if I have had to speak to them that morning. Humans are emotional and have difficultly simply turning off whatever is going on in their lives, especially children. My little girl whose uncle is in the hospital can’t concentrate on reading today because her mind is on the image of him being taken out of their house in an ambulance. The little boy who got in trouble on the bus is thinking about what his parents are going to say when he gets home – how can I expect him to concentrate on his math? They’re just kids – we need to keep that in mind when we’re making them jump through circus hoops called standardized testing. Another point that I thought was interesting was his quote from the 1992 National Assessment of Educational Progress report that stated a combination of four variables (number of parents living in the home, parent’s educational background, type of community, and poverty rate) could account for 89% of the differences in state scores. That number seems very high. Even if it’s 50%, that’s a tremendous amount. It’s very difficult to compare children, especially when we’re only using one type of comparison. How can we say that just because one child scored better on a state test, that child is automatically more intelligent and more gifted? Such comparisons certainly don’t take into account other forms of giftedness and the multiple intelligences. Module VIII I had never heard of dictation as a learning tool prior to this journal activity. That should have been a pretty good sign to me that it may not have all that much use in a classroom. When I studied up on it online, I found a website that supported the use of dictation in the classroom as a means of practicing the English language. Upon reading it, however, I did not find much use for it in my classroom. It seems kind of silly to spend all that time copying down exactly what the teacher says, especially if you may not even understand it. I can copy down words in Spanish and not know what they mean because I understand the Spanish alphabet and can spell fairly well in Spanish. The same applies to English. If I told my students to write the word “dook”, they would be able to do it because they know how to spell similar words (book and took,) but if doesn’t mean they understand the word. The website I visited gave several examples of what a teacher reads aloud and students copy. One of them had to do with names – what a waste of time!!! In my opinion, being able to write names like “Geoffrey” isn’t an important skill that needs addressing. Dictation reminded me very much of my second language instruction through good old dialogues. We memorized them – I can still remember some of them – and we practiced them over and over in class. So, I’ve been studying Spanish for 13 years now (technically) and I have visited two Spanish-speaking countries. Yet, I have never found a use for any of the dialogues we memorized in sixth and seventh grades. Language doesn’t work that way – I can’t say something and know exactly how the other person will respond! Maybe this is one of the reasons I had trouble conversing in Spanish for so many years – I didn’t know how to respond when the person said something I wasn’t expecting. Goodness knows I didn’t understand what they had said! I don’t think I will ever use dictation exercises in my classroom. I don’t really see the purpose in them. Module X Defining language proficiency is about as easy as defining assessment. It’s quite complicated and involves a variety of factors. It’s also important to remember that each person’s definition of proficient is different. What I’ve begun to assemble as a definition for this term is that it is the knowledge of a language that allows you to communicate to other speakers of the language in all facets, including speaking, writing, reading, and listening. (Communication involves both the output and the input.) To be “proficient” in a language, you can communicate freely and engage in a comfortable conversation – there may not be 100% correct usage and there may be a pause to think about what you are going to say or write, but all in all, a conversation is held. It’s difficult to assess language proficiency for the same reason it’s so hard to define it. There are so many different aspects to take into consideration. What I may consider to be proficient may not be what someone else does. For example, I worked with a woman once who had very little patience for those who speak languages other than English. (It’s very frustrating in that her main job is to deal with people who come into the office.) Anyway, the other day, one of my student’s fathers called after school hours to ask about a basketball camp that would be occurring that weekend. Somehow, the secretary heard that the child hadn’t come home from school yet and she was missing. I finally got in touch with the father and it turned out he was wondering if he could drop her off for the basketball camp and then pick her up afterwards, so that he could still go to work. While I was speaking to him in English, I thought to myself, “Wow – he speaks really great English for a parent of one of my ELLs.” And I couldn’t understand how the secretary didn’t understand him. Then I remembered that he has an accent, and to that secretary, a person is not proficient in a language unless he/she no longer has an accent. Language proficiency is also difficult to assess because there are two uses for a language – conversational and academic. Many of the ELLs are quite proficient when it comes to talking with friends in a relaxed atmosphere, however, in a classroom it’s a bit more trouble some for them. In such an academic environment, there are tons of new vocabulary terms and it’s hard to sometimes explain your thoughts when it comes to a book you’ve recently read or how you reached the answer in a math problem. Assessing language proficiency is, and always will be, a very subjective assessment. It was interesting to read everyone else’s observation reports. What some people observe that I may miss always interests me. It’s also neat to see through the eyes of someone with different experiences. It was quite enlightening to read Amy’s – I remember being that student who was just amazed by the classroom experience that it was difficult to critique anything. I think in five years, she will probably realize it was strange that the teacher didn’t call on the ELL student, regardless of her shyness. Anyway, I noticed a few common threads, but not as many as I thought I would. It appears that we all observed a variety of classrooms and English Language Learning setups. One thing I noticed was that many of the teachers used a variety of assessments besides tests. (Although I wish I would have been able to hear about a teacher’s experience with portfolios.) It seems that these teachers are aware of how best to assess their students, and if they aren’t, then at least they are using a variety of methods to do so. I also saw that in many of the classes, there were either a small number of students in the ELL classrooms or a second teacher was in the classroom. I liked the “push-in” observation – I would love to see how that works in a classroom versus the “pull-out” setup. It appeared that there were measures taken in each class to accommodate the needs of the English Language Learners. The only one that really stood out to me was Amy’s observation about the little girl. I wondered if this teacher really allows the ELLs to sit in the class and never participate. There are always ways to involve students, no matter how shy they are. I learned in one of the many workshops I attended that every child needs to be reached each day – it may be a smile, a pat on the back, a “hi”, or simply being called on, but children should not go through their day without some sort of acknowledgement from the teacher. I make it my goal to call on every child. What’s surprising is they don’t hate it, even if they’re not sure of the answer…actually, they love it.