Additional images are found on the website gallery

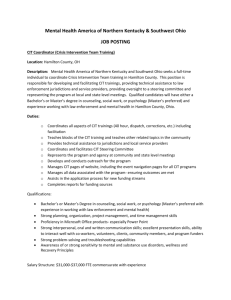

advertisement