The Language Policy Issues in Seoul: Hiring Native Speaker

advertisement

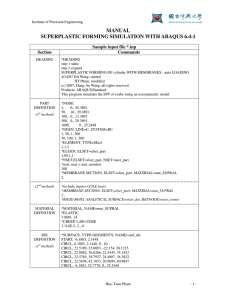

KyungHee Choi Dr. Higgins SLS 660 October 14, 2007 Paper #1 The Language Policy Issues in Seoul: Hiring Native Speaker English Teachers In recent years great attention has been focused on the question of hiring native Englishspeaking teachers in a number of Asian countries. The Foreign Expert (FE) scheme in China, the Native English Teacher (NET) scheme in Hong Kong, and the Japan Exchange and Teaching (JET) scheme in Japan (Jeon, & Lee, 2006) are good examples. Korea is not an exception, since the Communicative Language Teaching (CLT) approach was introduced in the Sixth National Curriculum for English in 1995 (Kwon, 2000; Nunan, 2003), and its use continued in the Seventh revision of the National Curriculum for English (Guilloteaux, 2004). Affiliated to the Ministry of Education and Human Resources Development, the English Program in Korea (EPIK) was formally established in 1995; with the purpose of fostering students’ English speaking proficiency, training teachers’ English communication ability, enhancing cultural awareness, developing English textbooks and materials, and improving English teaching methodologies (Ahn, Park, & Ono, 1998). To meet their schools’ increasing demand for placing native English-speaking teachers, each metropolitan or provincial office of education has started to take charge of their recruitment since 2004. One of those localized schemes, the Native Speaker English Teacher (NSET) scheme, operated by Seoul Metropolitan Office of Education (SMOE), is being considered in this paper, since it is a context that I am familiar with through my own teaching experiences. The goal of this paper is to better understand the current policy on hiring NSETs in Seoul, and to reflect upon the language ideologies. The following research questions are addressed: 1. What are the different perspectives of KETs, NSETs and students? The Language Policy Issues in Seoul 2. 2 Does the current policy work? Which aspects are successful? 3. What problems exist in the current policy? What can be improved? 4. What is the influence of English as a Lingua Franca on English Language Teaching? What implications does ELF have for the native speaker concept as a norm for ELT? CONTEXT: Learning and Teaching English In Korea there has been growing interest in English education among students, teachers, parents, publishers, policy makers, government officials and others. It is not surprising to see a variety of advertisements related to learning English on the street or in the subway. Jeong (2004) mentioned how much pressure to learn English exists in Korea, and described the whole country as in the grip of “English fever.” It is easy to find English-related articles in the newspaper such as, “the so called “English divide” is growing now that position, promotion and income may all depend on facility in the language…(The Chosun Ilbo, July 18, 2007)” Along with this social demand, the policy on hiring native English-speaking teachers in schools is organized by the Ministry of Education and Human Resources Development. According to the Hankook Gyoyook Newspaper (January 7, 2007), more than 1909 native English-speaking teachers work in the education system including primary and secondary schools as of April, 2006. The native English-speaking teachers came from diverse areas including 737 from Canada, 684 from the United States, 140 from New Zealand, 133 from Australia, 131 from Britain, 34 from Ireland, and 32 from South Africa. Currently, several agencies exist for recruiting foreign personnel: the EPIK (10.7%), metropolitan or provincial education offices (34.2%), local governments (15.2%), schools (34.0%), and the others (5.9%). The primary method for recruiting is through their own websites. The NSET scheme was launched by the SMOE with a Four-Year-Plan for English Education in Seoul. The SMOE announced “one NSET per school” policy, placing NSETs in The Language Policy Issues in Seoul 3 every elementary and junior high school by 2009, aiming to improve both students’ and teachers’ communication skills. Previously, only wealthy schools which have a large amount of school supporting fees hired native English-speaking teachers by themselves, so it caused problems such as an educational gap between schools or districts, and the recruitment of unqualified native-speaking English teachers. Also, the existing EPIK scheme does not much help to provide qualified native English-speaking teachers in Seoul, in that only 14 native English-speaking teachers are hired from EPIK program to go to Seoul so far (Seoul already benefits in many ways educationally and economically, so the national scheme, EPIK, does not focus on Seoul to cover the shortage of native English-speaking teachers in the rest of the country). In order to solve those problems and meet schools’ demand of placing native English-speaking teachers in Seoul, SMOE took charge of recruitment from 2004 and gave priority to schools in Seoul where the educational quality has not been good for placing native English-speaking teachers. NSETs conduct English classes in collaboration with Korean English teachers (KETs). A co-teaching system plays a significant role in the NSET scheme, but co-teaching is a complex issue. Time constraints, misconceptions in CLT with co-teaching, and KETs’ English proficiency are all factors that prevent them from working well in collaboration. In addition, in spite of the growing need for NSETs and the increasing number of NSETs, their deficiency in qualifications has always been an issue. The NSETs’ lack of teaching experience and professionalism are often pointed out. CURRENT LANGUAGE POLICY: the NSET scheme The NSET scheme is a new policy on hiring native English-speaking teachers although it is partially based on what EPIK has done. In contrast to the JET program I was not able to find any pamphlet or advertisement on NSET program; however I found some information on the official website of English Teachers in Seoul (ETIS) for NSETs. In order to become NSETs, The Language Policy Issues in Seoul 4 applicants must meet the qualifications as follows (ETIS website, 2006): 1. Hold a minimum of Bachelor’s degree from an accredited university. 2. Be a citizen from a country where the only official language is English. Canadian citizens from the Quebec Province where English is a co-official language must have been taught in English-language schools from junior high school forth to the university level. *Ethnic Korean applicants with foreign citizenships or legal residencies must have been taught in English-language schools from junior high school forth and have lived abroad for minimum of 10 years. (If you are a male citizen of the Republic of Korea under the age of 35, you must have either completed mandatory military service or have received an official waiver.) 3. Be fluent and proficient in the English language grammar and structure and be able to communicate fluently with clear and distinct pronunciation and manner. 4. Be mentally and physically capable of performing the specified responsibilities and duties. Must also have the ability and willingness to adapt to Korean culture and living. 5. Meet the criteria of eligibility for E2 (work) visa set forth by the Korean Immigration Authority. NSETs are employed on a renewable, one-year (52 weeks) contract basis, working 40 hours per week (however, actual class instruction hours are maximum 22 hours per week). Remuneration is varied depending on NSETs’ teaching experience and educational background. There are eight levels of pay from the lowest of 1.8 million Korean won (1,970 US dollars) to the highest of 2.7 million Korean won (2,952 US dollars) per month (23,640 ~ 35,424 US dollars annually). There are additional benefits such as: accommodation, round trip airfare, tax exemption, and a settlement allowance. Furthermore, their duties are carried out under the supervision of the administrator assigned by the SMOE. NSETs are responsible for (ETIS The Language Policy Issues in Seoul 5 website, 2006): 1. conducting English classes in cooperation with KETs, 2. preparing teaching materials and activities for English language education, 3. assisting with the development of teaching materials related to English language education, 4. assisting with activities related to English language education and other extracurricular activities such as judging English speech contest, voice recording for English listening comprehension tests, conducting English conversational classes in the English camp during the winter or summer vacation. According to the SMOE, 200 new NSETs are employed mostly from the USA, Canada, England, New Zealand, and Australia. They are mainly in their twenties or thirties, and have degrees in Education, hold teaching certifications, or hold English education-related certification such as ESL, TESL, and TESOL. NSETs also attend an orientation which includes learning the Korean language and Korean culture. Once a year they also need to attend the NSET workshop. METHOD To explore the research questions, I have referred to newspapers, websites, and government documents. Since the NSET scheme is quite a new one, there is not so much previous material to work with. In addition, a survey was sent to approximately 70 people as an email attachment to NSETs, KETs and students. However, only two NSETs, two KETs and three students completed it, and the response rate was only 11%. However, at this time there was one of the biggest holidays in Korea, and after that, the students had a mid-term test period. Thus, follow-up interviews based on qualitative section (open-ended questions) of the survey were used to analyze the data. Based on their responses, it is possible to mention their satisfaction or dissatisfaction with teaching and learning in Korea. Despite the small number of participants, The Language Policy Issues in Seoul 6 there are distinct perspectives about the NSET program among KETs, NSETs and the students. FINDINGS Assessment of the NSET scheme According to surveys (ETIS website, 2006) conducted by the SMOE in 2005, Korean teachers, students and their parents were satisfied with the NSET program. The SOME said that “through a co-teaching system, students have opportunities to speak with native speakers of English and are able to decrease their fear of a foreign language. In addition, young students motivate themselves studying English while working with various activities” on its website. Based on the positive results of the NSET implementation, the SMOE plans to hire NSETs in more elementary and junior high schools. However, it should carefully examine the question of its success and more reliable surveys need to be done. Based on what I have examined, experienced, and researched, I would like to discuss further what is working, what is not working, and why. Positive Aspects of The NSET Scheme (a) Success in affective factors such as motivation and fear To a certain extent, the NSET program is working well. No one disagrees that having a NSET in schools motivates students and gives them a positive influence about English. While students are working with the NSET, they are motivated to learn English and their fear and anxiety of using a foreign language like English or talking with foreigners. The NSETs, the KETs and the students said that such as: “Definitely – some students are not interested in English and for those students, NSETs will make no difference. But for most students I believe they are more motivated to learn because of the NSET program. I think the scheme is definitely working but its impossible to gauge in a tangible way. Go to any school and see how the students get excited by the The Language Policy Issues in Seoul 7 NSETs, how they interact with them and the atmosphere they bring to the school. That’s where the success lies – in the everyday running of the school.”(NSET, S.) “Students enjoy learning with an NSET more than a KET. It is exciting for them. The students are learning and they enjoy the company of the NSETs.”(NSET, F.) “Learning from a NSET could be good for motivating students.”(KET, J.) “I had no interest in English, but I have some interest now through the NSET. Also, I’m not embarrassed to see other foreigners and I can approach them.”(Student, H.) (b) Effort of solution to “English Divide” As I mentioned earlier, there are problems such as an educational gap between schools or districts, since only wealthy schools which have a large amount of budget recruit native Englishspeaking teachers. Through the NSET scheme, the SMOE has been placed NSETs to schools in poor districts with the priority order. As the table 1 (Seoul Education News, 2006) indicates, it rarely provided NSETs to the school districts of Gangdong (GD) and Gangnam (GN) which are considered as wealthy districts in Seoul. This gives a potential solution to the English Divide. Name of Dong Seo Nam Buk Joong Gang Gang Gang Dong Seong Seong School Bu Bu Bu Bu Bu Dong Seo Nam Jak Dong District (DB) (SB) (NB) (BB) (JB) (GD) (GS) (GN) (DJ) (SD) (SB’) Elem- 2005 7 6 5 6 4 1 5 0 6 6 4 (50) 11 11 12 12 9 2 11 0 9 13 10 100 Junior 2005 High 6 6 5 10 3 2 2 0 6 3 7 (50) School 2006 11 8 13 13 5 7 11 4 11 5 12 100 Total (2006) 22 19 25 25 14 9 22 4 20 18 22 200 Buk Total entary School 2006 Table 1: The number of NSETs’ placement to each school district as of September, 2006 Most people would agree that the poor students do not have any opportunity to use English, or The Language Policy Issues in Seoul 8 even to see a native-speaking English teacher. Furthermore, the schools increase a variety of activities in English. NSETs assistance in English-related activities enlarges English programs in public schools. According to the SMOE (Seoul Education News, 2007), there has been English conversational classes held in English camps during summer and winter, and NSETs are judging English speech contests. Moreover, they assist with materials development like making voice recording for English listening comprehension tests. The NSETs also participate with KETs in running the English-only zones in schools which are similar to English villages that give students more opportunities to be involved in English activities. Problematic Aspects of The NSET Scheme Although the NSET program can be seen to have advantageous aspects and seems to be working, there are some problems in terms of the goal of the program. The main goal of the program is not to help students to be motivated or to overcome their fears of speaking English with foreigners; but it is to improve students’ English proficiency. (a) The ratio of NSETs to schools: “One NSET per school” The NSETs said that such as, “Absolutely, the students that put effort into talking to NSETs and are motivated to talk to NSET’s definitely improve their speaking proficiency,” and “KETs can teach the same content and use the same activities but the students are not forced to use English and the NSET also has the advantage of a native accent.” KETs agreed that the NSET program led students to be motivated and excited, but the program seemed not to be working very much when it comes to its effectiveness for students’ progress in English speaking. They said it would be better than having nothing, however, because of the ratio of NSETs to schools made this program useless. On the students’ part, they said they were having fun in classes with NSET, but they could The Language Policy Issues in Seoul 9 not understand and participate in classroom activities without KET. This implies how important collaborative teaching is for the students and indicates their degree of proficiency. They do not see themselves as improving their speaking proficiency although they happened to have less fear and anxiety toward foreigners. “I do not think my speaking proficiency has increased.” (Student, M.) “I do not understand NSET, so I have to ask KET. I’m afraid of English classes. Since I don’t understand English much, if I have a class with NSET, I become so nervous and worried.” (Student, E.) “Others may be improved, but I did not participate well. So, my proficiency is still in the same level.”(Student, H.) As Nunan (2003) pointed out “to achieve consistent and measurable improvements in the target language, learners need adequate exposure to it.” However, the students do not receive enough input because there is only one NSET per school, although the program may provide opportunities for learning English with the NSET. The students need to be more exposed to English. If the program does not provide more interaction in English instead of providing one hour a week for students, the NSET scheme is useless. (b) Failure in co-teaching As I mentioned before, collaborative teaching is an important factor in the NSET scheme. When students can not understand and participate in classroom activities, the KETs need to provide adequate instructions to students. However, a lack of KETs’ proficiency often caused a poor co-teaching. There is a lack of interaction between NSETs and KETs which is caused by KETs’ lack of language proficiency, although there are other factors like time-constraints. One of KETs said that, “There are different teaching styles, different cultural backgrounds and misunderstanding. To cope with those problems, by having conversation is of course hard.” The Language Policy Issues in Seoul 10 In addition, one of main reasons that co-teaching is not working is because both NSETs and KETs have misunderstandings about it. The NSETs and KETs said such as: “My co-teacher does nothing – I do all of the planning.”(NSET, F.) “Co-teaching is not that effective. Some Korean English teachers feel they are being assistants not co-teachers.” (KET, J.) The case in which one teacher performs a lesson and the other stands or sits by and watches, or one teacher decides what is to be taught or how it will be taught is not about co-teaching (Villa, Thousand, & Nevin, 2004). Because of cultural differences, age differences among other reasons, there exists the question of how NSETs and KETs will collaborate. Park Won-young, president of Korea Secondary English Teachers’ Association said, “Native English-speaking teachers are not only for the benefit of students but also Korean teachers. But the reality is different when the foreign teachers attend the classes, many Korean teachers stay out of class and take a rest.” (The Hankook Ilbo, November 15, 2006) (c) Low participation in Korean English teacher training Since many English-related activities increased in the schools, the SMOE and schools urge the KETs to be trained to practice their communication abilities in English. However, one of the KETs said that the English teachers training program did not function well. She mentioned it seemed that senior teachers were reluctant to participate in the programs, because most trainees of the courses were young Korean instructors (Age relationship in Korea is important, since we have learned that the younger should give precedence to the elder). However, I see participation in English teacher training as potentially improving, since the SMOE announced in September, 2006 that the NSETs will work to improve KETs’ speaking proficiency, and there will be obligatory courses every three years. KETs’ school-driven training is more difficult to implement compared to ministry-driven The Language Policy Issues in Seoul 11 training. When I was working at a junior high school, there was conversational practice in English with a NSET. However, when it came to KETs’ participation, it failed. Out of the ten KET on staff, only one KET participated. These poor results are often related to their level of English proficiency, but the reasons are difficult to quantify. However, to encourage KETs to join in the conversational class, it would be a good idea to run one class for KETs and another class for the other teachers. (d) Imbalance between the policy and reality The KETs’ communication skills and training is important, since the NSET program is mainly focused on a CLT approach. Language is viewed as a means of communication, thus the forms and meanings are just a part of communicative competence (Larsen-Freeman, 2000). However, English classes still seem deeply committed to grammar and vocabulary, and not speaking and listening. There is a huge gap between CLT and curriculum as well as CLT and materials. KETs often complained about how hard it is to satisfy everything such as entrance exams, grammar and reading oriented lessons and parents and principal’s expectations. Guilloteaux (2004) mentioned that, “most teachers approve of the theory behind CLT but many of them are not enthusiastic about putting it into practice in their own classrooms because they often feel that it is not applicable to their contexts.” In addition, English as a Lingua Franca(ELF) and English as an International Language (ELI) with globalization influenced on the English language teaching, and its effect created a policy on hiring native English-speaking teachers, but there is a huge gap between the realities of the ELT context and administrative rhetoric. Seidlhofer (2005, cited in Jenkins, 2006) mentioned that “much of the problem results from a mismatch the meta level, where WEs and ELF scholars are asserting the need for pluricentrism, and ‘grassroots practice’, where there is still ‘(unquestioning) submission to native-speaker norms’.” The policy-makers of the NSET scheme The Language Policy Issues in Seoul 12 did not seem to aware of perspectives in applied linguistics regarding ELF and ELI, in that they made some criteria such as “be a citizen from a country where the only official language is English,” and “be fluent and proficient in the English language grammar and structure and be able to communicate fluently with clear and distinct pronunciation and manner.” Moreover, the NSETs I surveyed seemed to have a strong sense of “ownership of English” (Widdowson, 1994, cited in Jenkins, 2006) even though they were aware of teaching other varieties of English into classrooms. One of NSETs said that, “as an Australian I haven’t had any problems. We have to accept that North American English is the recognized form of English spoken and taught in Korea. The system should be flexible and open enough to consider other types of English and other accents,” and then made a contradictory statement, “Inner-circle countries only! English speakers from other countries are not ‘native’ speakers!” CONCLUSION This paper has attempted to sketch out the positive and problematic aspects of the NSET scheme, and has pointed out possible suggestions to the negative aspects. Summing up all of the preceding reasoning and returning to the question posed at the outset of the paper, it seems appropriate to state that the NSET scheme does not seem to be working very well in the point of achieving English speaking proficiency among Korean students, although it sounds like the success lies in affective factors. However, it is too early to present a detailed assessment of the success of the NSET scheme, for it started a several years ago. The present study is the first to examine and research the NSET scheme except the policy-making agency, the SMOE. Also, the present paper was limited in scope, thus further studies on different large scale assessments are needed. REFERENCES The Language Policy Issues in Seoul 13 Ahn, S., Park, M, & Ono, S. (1998). A comparative study of the EPIK program and the JET program. English Teaching 53(3), 241-267. Chosun Ilbo. (Julu 18, 2007) 'English Divide' Grows Between People, Nations http://english.chosun.com/w21data/html/news/200707/200707180014.html ETIS Website (2006). English Teachers in Seoul. http://etis.sen.go.kr/ Guilloteaux, M. (2004). Korean teachers’ practical understanding of CLT. English Teaching 59(3), 53-76. Hankook Gyoyook Newspaper (January 7, 2007). Native English-speaking teachers to all elementary schools and junior high schools in Seoul http://www.hangyo.com/APP/news/article.asp?idx=20447&search=원어민 Hankook Ilbo. (Novemeber 15, 2006) Teachers Sour Over English Training Plan http://search.hankooki.com/times/times_view.php?term=jaehyeok++&path=hankooki3/times/lpage/200611/kt2006111517402110160.htm&media=kt Jenkins, J. (2006). Current perspectives on teaching World Englishes and English as a Lingua Franca. TESOL Quarterly 40(1), 157-181. Jeon, M. & Lee, J. (2006). Hiring native-speaking English teachers in East Asia countries. English Today 22(4), 53-58. Jeong, Y-K. (2004). A chapter of English teaching in Korea. English Today 20(2), 40-46. Kwon, O. (2000). Korea’s English education policy changes in the 1990s: Innovations to gear the nation for the 21st centry. English Teaching 55, 47-91 Larsen-Freeman, D. (2000). Techniques and principles in language teaching. Oxford University Press. Nunan, D. (2003). The impact of language as a global language on educational policies and practices in the Asia-Pacific region. TESOL Quarterly 37(4), 589-613. The Language Policy Issues in Seoul 14 Seoul Education News (September 4, 2006). The SMOE, NSETs’ replacement to schools. 47. Seoul Education News (January 16, 2007). Education office of the school district held English camps. 63. Villa, R., Thousand, J. & Nevin, A. (2004) A Guide to Co-Teaching: Practical Tips for Facilitating Student Learning. Florida International University.

![[Slogan] Proposal for Seoul Brand Idea Contest](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/006838769_1-d7653e11f28783f70bcf6bf0f4022941-300x300.png)